Triangle Inequality

The triangle inequality is one of those results that sounds obvious until you try to prove it rigorously. Here’s the geometric intuition: no side of a triangle can be longer than the other two sides combined. If it were, you couldn’t close the triangle. Simple enough. But this same principle extends to real numbers, complex numbers, vectors, and abstract spaces—and the proofs get increasingly elegant.

The Geometric Idea

Consider a triangle with sides \( a \), \( b \), and \( c \). The triangle inequality states:

- \( a < b + c \)

- \( b < a + c \)

- \( c < a + b \)

When does equality hold? Only in the degenerate case where the “triangle” collapses into a straight line. Think about it: side \( a \) equals \( b + c \) exactly when points \( B \) and \( C \) lie on the line segment from \( A \). Not really a triangle anymore.

Triangle Inequality for Real Numbers

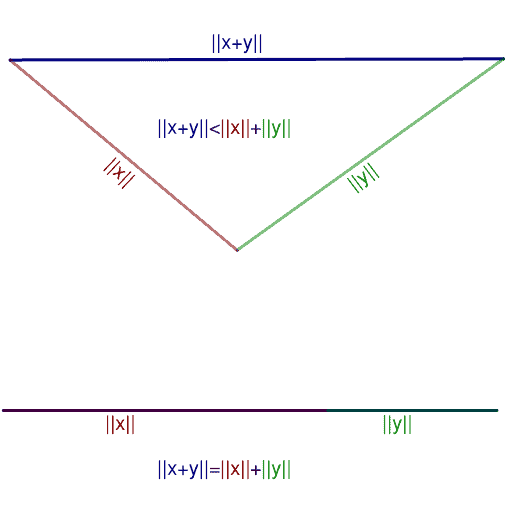

The real-number version uses absolute values. For any real numbers \( x \) and \( y \):

$$ |x + y| \leq |x| + |y| $$

Here, \( |x| \) represents the distance from \( x \) to zero on the number line. So \( |5| = |-5| = 5 \).

The proof requires a useful lemma first.

Key Lemma

Lemma: For \( a \geq 0 \), we have \( |x| \leq a \) if and only if \( -a \leq x \leq a \).

Proof:

Forward direction: Suppose \( |x| \leq a \). Then \( -|x| \geq -a \). Since \( |x| \) equals either \( x \) or \( -x \), we always have \( -|x| \leq x \leq |x| \). Combining these:

\( -a \leq -|x| \leq x \leq |x| \leq a \)

So \( -a \leq x \leq a \). ✓

Reverse direction: Assume \( -a \leq x \leq a \). If \( x \geq 0 \), then \( |x| = x \leq a \). If \( x < 0 \), then \( |x| = -x \leq a \) (since \( x \geq -a \) implies \( -x \leq a \)). Either way, \( |x| \leq a \). ✓

Main Proof

We know that \( -|x| \leq x \leq |x| \) and \( -|y| \leq y \leq |y| \).

Adding these inequalities:

\( -(|x| + |y|) \leq x + y \leq |x| + |y| \)

By the lemma (with \( a = |x| + |y| \)):

\( |x + y| \leq |x| + |y| \) ✓

Generalization to n Terms

The inequality extends to any finite sum:

$$ |x_1 + x_2 + \cdots + x_n| \leq |x_1| + |x_2| + \cdots + |x_n| $$

Or in sigma notation:

$$ \left| \sum_{k=1}^{n} x_k \right| \leq \sum_{k=1}^{n} |x_k| $$

This follows by induction, applying the two-variable case repeatedly.

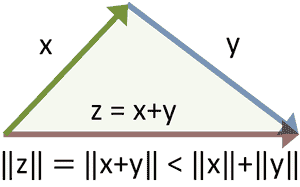

Triangle Inequality for Vectors

For vectors \( \mathbf{A} \) and \( \mathbf{B} \) in a vector space \( V_n \):

$$ \|\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B}\| \leq \|\mathbf{A}\| + \|\mathbf{B}\| $$

Here \( \|\mathbf{A}\| \) denotes the norm (length) of vector \( \mathbf{A} \), defined as:

\( \|\mathbf{A}\| = \sqrt{\mathbf{A} \cdot \mathbf{A}} \)

Proof

Starting from the definition:

$$ \|\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B}\|^2 = (\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B}) \cdot (\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B}) $$

$$ = \mathbf{A} \cdot \mathbf{A} + 2(\mathbf{A} \cdot \mathbf{B}) + \mathbf{B} \cdot \mathbf{B} $$

$$ = \|\mathbf{A}\|^2 + 2(\mathbf{A} \cdot \mathbf{B}) + \|\mathbf{B}\|^2 \tag{1} $$

Meanwhile:

$$ (\|\mathbf{A}\| + \|\mathbf{B}\|)^2 = \|\mathbf{A}\|^2 + 2\|\mathbf{A}\|\|\mathbf{B}\| + \|\mathbf{B}\|^2 \tag{2} $$

The key insight: by the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality:

\( \mathbf{A} \cdot \mathbf{B} \leq \|\mathbf{A}\| \|\mathbf{B}\| \)

Comparing (1) and (2), we see that \( \|\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B}\|^2 \leq (\|\mathbf{A}\| + \|\mathbf{B}\|)^2 \).

Taking square roots (both sides are non-negative):

\( \|\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B}\| \leq \|\mathbf{A}\| + \|\mathbf{B}\| \) ✓

Triangle Inequality for Complex Numbers

For complex numbers \( z_1 \) and \( z_2 \):

$$ |z_1 + z_2| \leq |z_1| + |z_2| $$

The proof is essentially identical to the vector case. Complex numbers behave like 2D vectors under addition, and the modulus \( |z| \) corresponds to vector length. Just replace \( \mathbf{A} \) and \( \mathbf{B} \) with \( z_1 \) and \( z_2 \), and the argument carries through.

Triangle Inequality in Euclidean Space \( \mathbb{R}^n \)

Now for the most general setting. Let me build up the machinery we need.

The Set \( \mathbb{R}^n \)

The set \( \mathbb{R}^n \) consists of all ordered n-tuples of real numbers:

\( \mathbf{x} = (x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n) \)

We define addition and scalar multiplication componentwise:

\( \mathbf{x} + \mathbf{y} = (x_1 + y_1, x_2 + y_2, \ldots, x_n + y_n) \)

\( c\mathbf{x} = (cx_1, cx_2, \ldots, cx_n) \)

The zero vector and negatives are defined naturally:

\( \mathbf{0} = (0, 0, \ldots, 0) \)

\( -\mathbf{x} = (-x_1, -x_2, \ldots, -x_n) \)

Distance in \( \mathbb{R}^n \)

The distance between points \( \mathbf{x} \) and \( \mathbf{y} \) is:

$$ d(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y}) = \sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^{n} (x_i – y_i)^2} $$

This is the familiar Euclidean distance, generalized to \( n \) dimensions.

The Norm

The norm of \( \mathbf{x} \) is its distance from the origin:

$$ \|\mathbf{x}\| = \sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^{n} x_i^2} $$

Note that \( d(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y}) = \|\mathbf{x} – \mathbf{y}\| \). The norm generalizes absolute value to higher dimensions.

Properties of Euclidean Space

The set \( \mathbb{R}^n \) with this distance function is called Euclidean n-space. The distance satisfies four key properties:

| Property | Statement | Name |

|---|---|---|

| A | \( d(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y}) \geq 0 \) for all \( \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y} \) | Non-negativity |

| B | \( d(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y}) = 0 \Leftrightarrow \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{y} \) | Identity of indiscernibles |

| C | \( d(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y}) = d(\mathbf{y}, \mathbf{x}) \) | Symmetry |

| D | \( d(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y}) \leq d(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{z}) + d(\mathbf{z}, \mathbf{y}) \) | Triangle inequality |

Properties A, B, and C follow directly from the definition. Property D is the triangle inequality—let’s prove it.

Proof of the Triangle Inequality in \( \mathbb{R}^n \)

Theorem: For all \( \mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y}, \mathbf{z} \in \mathbb{R}^n \):

\( d(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y}) \leq d(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{z}) + d(\mathbf{z}, \mathbf{y}) \)

Proof: First, we establish the norm inequality. From the definition:

$$ \|\mathbf{x} + \mathbf{y}\|^2 = \sum_{i=1}^{n} (x_i + y_i)^2 $$

$$ = \sum_{i=1}^{n} x_i^2 + 2\sum_{i=1}^{n} x_i y_i + \sum_{i=1}^{n} y_i^2 $$

By the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality:

$$ \sum_{i=1}^{n} x_i y_i \leq \sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^{n} x_i^2} \cdot \sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^{n} y_i^2} = \|\mathbf{x}\| \|\mathbf{y}\| $$

Substituting:

$$ \|\mathbf{x} + \mathbf{y}\|^2 \leq \|\mathbf{x}\|^2 + 2\|\mathbf{x}\|\|\mathbf{y}\| + \|\mathbf{y}\|^2 = (\|\mathbf{x}\| + \|\mathbf{y}\|)^2 $$

Taking square roots:

$$ \|\mathbf{x} + \mathbf{y}\| \leq \|\mathbf{x}\| + \|\mathbf{y}\| \tag{*} $$

Now here’s the clever step. Since (*) holds for all vectors, it holds when we substitute \( \mathbf{x} – \mathbf{z} \) for \( \mathbf{x} \) and \( \mathbf{z} – \mathbf{y} \) for \( \mathbf{y} \):

$$ \|(\mathbf{x} – \mathbf{z}) + (\mathbf{z} – \mathbf{y})\| \leq \|\mathbf{x} – \mathbf{z}\| + \|\mathbf{z} – \mathbf{y}\| $$

$$ \|\mathbf{x} – \mathbf{y}\| \leq \|\mathbf{x} – \mathbf{z}\| + \|\mathbf{z} – \mathbf{y}\| $$

Converting to distance notation:

$$ d(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y}) \leq d(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{z}) + d(\mathbf{z}, \mathbf{y}) \quad \checkmark $$

Summary: Triangle Inequality Across Different Spaces

| Space | Triangle Inequality | Key Tool in Proof |

|---|---|---|

| Real numbers | \( |x + y| \leq |x| + |y| \) | Properties of absolute value |

| Complex numbers | \( |z_1 + z_2| \leq |z_1| + |z_2| \) | Cauchy-Schwarz inequality |

| Vectors in \( V_n \) | \( \|\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B}\| \leq \|\mathbf{A}\| + \|\mathbf{B}\| \) | Cauchy-Schwarz inequality |

| Euclidean \( \mathbb{R}^n \) | \( d(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y}) \leq d(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{z}) + d(\mathbf{z}, \mathbf{y}) \) | Cauchy-Schwarz inequality |

Why the Triangle Inequality Matters

The triangle inequality isn’t just a curiosity. It’s foundational for:

- Metric spaces: Any function satisfying properties A-D above is called a “metric.” The triangle inequality is what makes distance behave sensibly.

- Analysis: Proofs about convergence, continuity, and limits constantly use this inequality to bound errors.

- Optimization: Many algorithms depend on the fact that the direct path is never longer than a detour.

- Machine learning: Distance-based algorithms (k-nearest neighbors, clustering) rely on triangle inequality for efficient search structures.

Bonus: The Reverse Triangle Inequality

There’s also a lower bound. For real numbers:

$$ ||x| – |y|| \leq |x + y| $$

And for vectors/norms:

$$ |\|\mathbf{A}\| – \|\mathbf{B}\|| \leq \|\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B}\| $$

This follows directly from the standard triangle inequality by clever substitution. Together, these give you both upper and lower bounds on the length of a sum.

Key Takeaways

- The triangle inequality says the direct path is never longer than a detour

- It holds for real numbers, complex numbers, vectors, and Euclidean space

- The Cauchy-Schwarz inequality is the key tool for proving it in higher dimensions

- It’s one of three properties (with non-negativity and symmetry) that define a metric

- The reverse triangle inequality provides a corresponding lower bound

Hi Gaurav. Nice post, I will include this in the next Math and Multimedia Carnival. By the way, if you can lower the level of your posts to high school level, I can invite to as a guest blogger.

Thanks Guillermo for the compliment! I usually write on basic topics in mathematics —however this is not the one. :)

I am greatly surprised, that how could you do this? Great post. I could only get that the longest side of a triangle is always less than the sum of other two sides

very interesting post.