Rolle’s Theorem Calculator

Use this free Rolle’s Theorem Calculator to verify the conditions of Rolle’s theorem and find all values of c where f'(c) = 0 on a closed interval. Enter your function and bounds, and the calculator checks continuity, differentiability, and equal endpoint values, then locates the critical points with an interactive graph.

Find values of c where f'(c) = 0, given f(a) = f(b) on a continuous, differentiable function.

Theorem Conditions

Result

Graph

Details

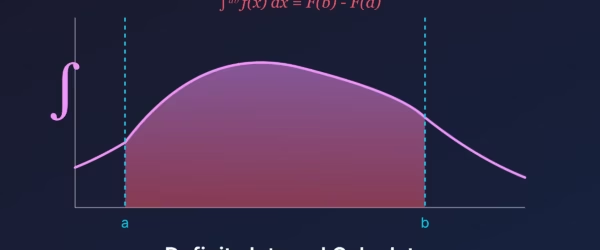

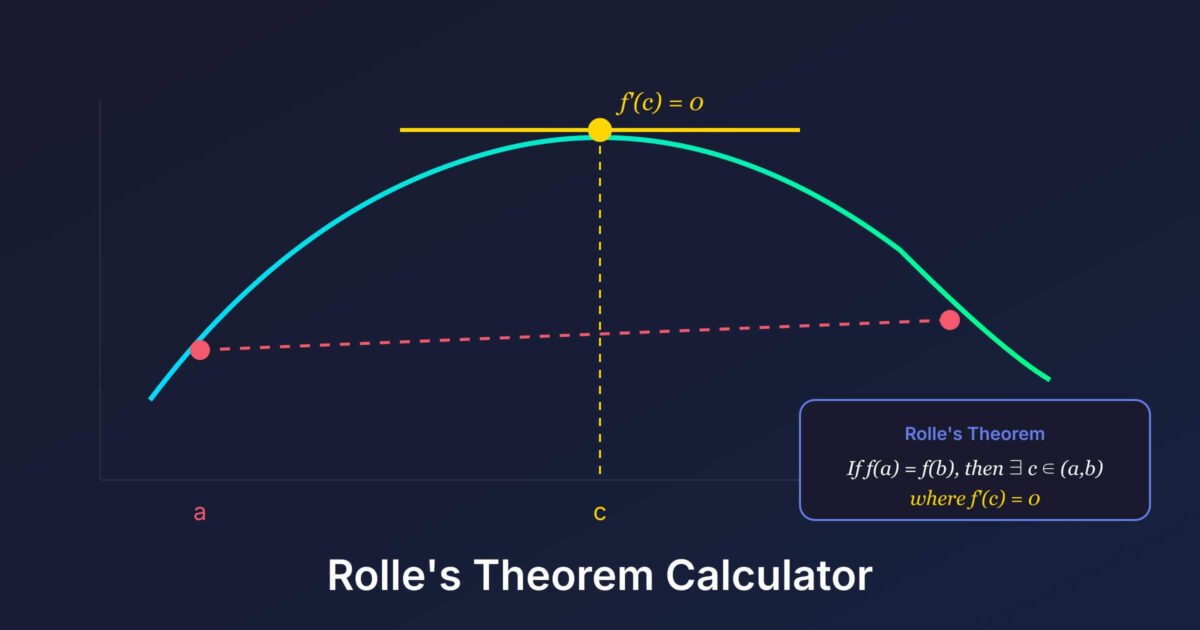

What is Rolle’s Theorem?

Rolle’s Theorem states that if a function is continuous on a closed interval, differentiable on the open interval, and has equal values at the endpoints, then there’s at least one point where the derivative equals zero.

Named after French mathematician Michel Rolle, this theorem is foundational to calculus and provides a stepping stone to the Mean Value Theorem.

The Three Conditions

1. Continuous on \( [a, b] \)

\( f(x) \) must be continuous on the closed interval \( [a, b] \). No breaks or jumps allowed.

2. Differentiable on \( (a, b) \)

\( f(x) \) must be differentiable on the open interval \( (a, b) \). No sharp corners or vertical tangents.

3. Equal Endpoints

\( f(a) \) must equal \( f(b) \). The function starts and ends at the same height.

The Conclusion

If all three conditions are met, then:

$$\exists \, c \in (a, b) : f'(c) = 0$$

There exists at least one point \( c \) in the open interval where the tangent line is horizontal.

Intuitive Understanding

Think of a hike that starts and ends at the same elevation. If you start and end at the same height, you must have reached either a peak or a valley somewhere along the way. At that highest or lowest point, the ground is momentarily level, meaning the slope (derivative) is zero.

Related Theorems

Mean Value Theorem

Generalizes Rolle’s Theorem. For any continuous, differentiable function, there’s a point where the instantaneous rate of change equals the average rate of change over the interval.

$$f'(c) = \frac{f(b) – f(a)}{b – a}$$

Rolle’s Theorem is the special case where \( f(a) = f(b) \), making the right side equal to zero.

Extreme Value Theorem

A continuous function on a closed interval attains both a maximum and minimum value. Rolle’s Theorem tells us where to look for them.

Examples

Example 1: \( f(x) = x^2 – 4x + 3 \) on \( [1, 3] \)

- \( f(1) = 0 \), \( f(3) = 0 \) ✓

- Continuous and differentiable ✓

- \( f'(x) = 2x – 4 = 0 \to c = 2 \)

Example 2: \( f(x) = \sin(x) \) on \( [0, \pi] \)

- \( f(0) = 0 \), \( f(\pi) = 0 \) ✓

- Continuous and differentiable ✓

- \( f'(x) = \cos(x) = 0 \to c = \frac{\pi}{2} \)

Why Rolle’s Theorem Matters

Rolle’s Theorem isn’t just a theoretical curiosity. It’s used to prove:

- The Mean Value Theorem

- That polynomials of degree n have at most n real roots

- Uniqueness of solutions to differential equations

FAQs

What happens if one of Rolle’s Theorem conditions isn’t met?

The theorem’s conclusion may fail. For f(x) = |x| on [-1, 1], the function is continuous and f(-1) = f(1) = 1, but it’s not differentiable at x = 0 (sharp corner). There’s no point where f'(c) = 0. Similarly, if f(a) ≠ f(b), the function could be strictly increasing or decreasing with no horizontal tangent.

How is Rolle’s Theorem related to the Mean Value Theorem?

Rolle’s Theorem is a special case of the Mean Value Theorem (MVT). The MVT says there exists c where f'(c) = (f(b)-f(a))/(b-a). When f(a) = f(b), this simplifies to f'(c) = 0, which is exactly Rolle’s Theorem. In fact, Rolle’s Theorem is often used to prove the MVT by applying it to an auxiliary function.

Can there be more than one point where f'(c) = 0?

Yes, Rolle’s Theorem guarantees at least one such point, but there can be many. Consider f(x) = sin(x) on [0, 2π]. Here f(0) = f(2π) = 0, and f'(x) = cos(x) = 0 at both x = π/2 and x = 3π/2. The theorem provides a minimum guarantee, not an exact count.

Why does the function need to be continuous on the closed interval but only differentiable on the open interval?

Continuity on [a, b] ensures the function is defined at the endpoints and has no jumps. Differentiability is only required on (a, b) because derivatives at endpoints require limits from both sides, which don’t exist at boundary points. A function like √x on [0, 1] is continuous everywhere but has undefined derivative at x = 0 (vertical tangent), yet Rolle’s Theorem can still apply.

How do you find the value of c guaranteed by Rolle’s Theorem?

First verify all three conditions are met. Then find f'(x) and solve f'(x) = 0 for x in the open interval (a, b). For f(x) = x³ – 3x on [-√3, √3], we have f(-√3) = f(√3) = 0. Taking f'(x) = 3x² – 3 = 0 gives x = ±1. Both values lie in the interval, so c = 1 or c = -1.

What’s the geometric meaning of Rolle’s Theorem?

Geometrically, if a smooth curve starts and ends at the same height, it must have a horizontal tangent somewhere in between. Picture drawing a curve from point A to point B where both have the same y-coordinate. You can’t draw a smooth curve that goes up and then down (or down then up) without having at least one peak or valley where the curve is momentarily flat.

How is Rolle’s Theorem used to count polynomial roots?

Rolle’s Theorem proves that between any two roots of a polynomial, there must be a root of its derivative. A polynomial of degree n has derivative of degree n-1. If the original had more than n roots, the derivative would have more than n-1 roots, and so on. This chain of reasoning shows a degree-n polynomial can have at most n real roots.

Does Rolle’s Theorem work for complex functions?

Not directly. Rolle’s Theorem is a real analysis result that depends on the ordering of real numbers and the intermediate value theorem. Complex numbers aren’t ordered, so the theorem doesn’t translate directly. However, complex analysis has its own powerful results about zeros of analytic functions, including connections between zeros of a function and its derivative.