Mean Value Theorem Calculator & Grapher

Here’s the deal: calculating the rate of change of a function by hand is tedious. The Mean Value Theorem (MVT) gives you a powerful shortcut, and this calculator does the heavy lifting for you.

I built this tool to find those critical points where the instantaneous rate of change equals the average rate of change. It also graphs everything and computes derivatives automatically. Let me show you how it works.

Mean Value Theorem Calculator & Grapher

Click the button above to launch the Mean Value Theorem calculator and grapher. If the button doesn't appear, your browser may lack proper JavaScript support. Try Google Chrome or any modern browser. Works on mobile devices too.

Quick note: The \( x_{\min} \) and \( x_{\max} \) values are just for graph display range. They don't affect the MVT calculation itself—adjust them to zoom in or out on your function.

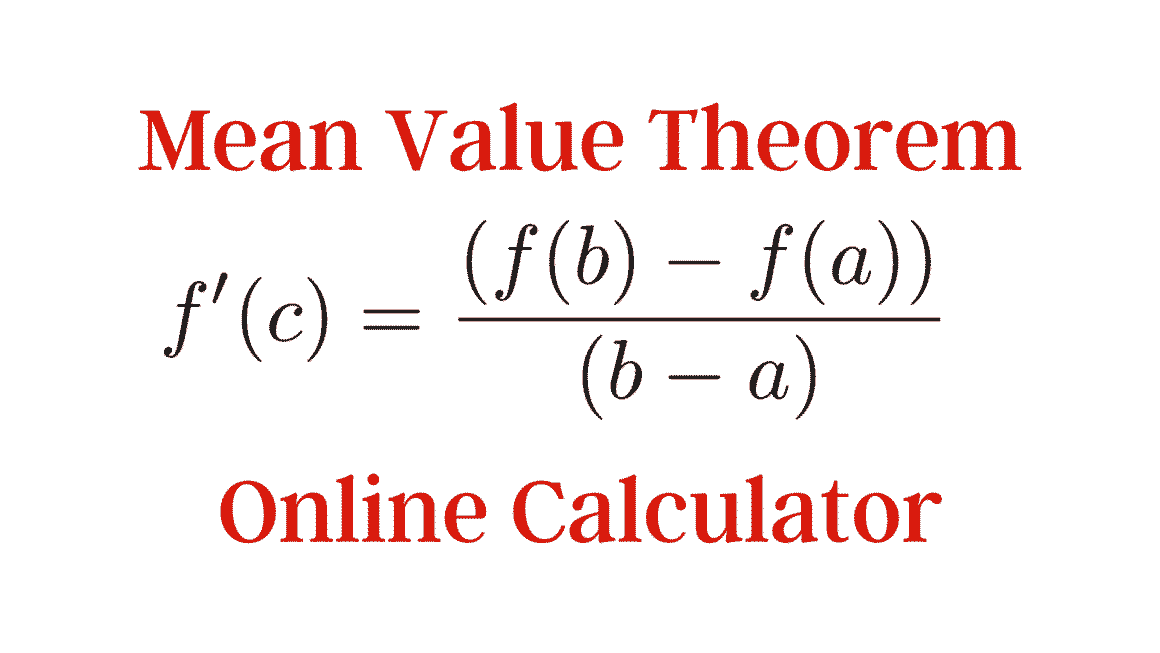

What is the Mean Value Theorem?

The Mean Value Theorem is one of calculus's most powerful tools. It tells you something intuitive: if you drive 60 miles in one hour, at some point during that trip, your speedometer must have read exactly 60 mph.

More formally, here's what MVT guarantees:

If \( f \) is continuous on the closed interval \( [a, b] \) and differentiable on the open interval \( (a, b) \), then there exists at least one point \( c \) in \( (a, b) \) where:

$$f'(c) = \frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a}$$

In plain English: somewhere between \( a \) and \( b \), the instantaneous rate of change equals the average rate of change over the entire interval.

The formal statement: If \( f(x) \) is defined and continuous on \( [a, b] \) and differentiable on \( (a, b) \), then there exists at least one number \( c \) in the interval \( (a, b) \) (meaning \( a < c < b \)) such that $$f'(c) = \frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a}$$

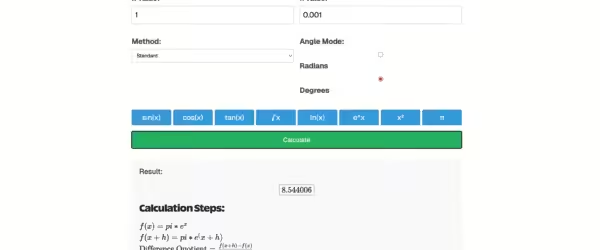

How to Use the Calculator

I designed this calculator to be straightforward. Here's the process:

- Enter your function in the \( f(x) \) field using standard mathematical notation (use

^for exponents,*for multiplication). - Set your interval endpoints \( a \) and \( b \). These are the bounds where MVT applies.

- Adjust the graph range if needed using \( x_{\min} \) and \( x_{\max} \).

- Click the launch button. The calculator finds all values of \( c \) where the tangent line is parallel to the secant line.

The graph shows your function in blue, the secant line (connecting endpoints) in red, and the tangent line(s) at the critical point(s) in green.

Why Use This Calculator?

Let's be real—you could solve MVT problems by hand. But here's what this tool gives you:

- Speed: Results in seconds, not minutes of algebraic manipulation.

- Visual understanding: The graph shows exactly where and why the theorem works.

- Multiple solutions: The calculator finds all valid \( c \) values, not just one.

- Error-free computation: No arithmetic mistakes in derivative calculations.

- Free and accessible: Use it anywhere, anytime—no software installation needed.

For students, teachers, and professionals working through calculus problems, this is a serious time-saver.

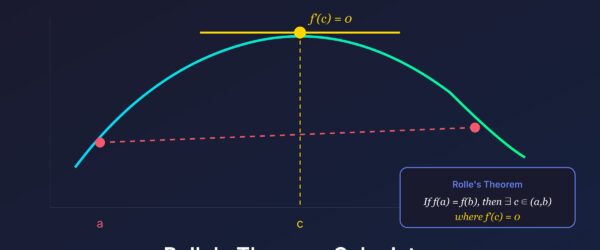

Rolle's Theorem: A Special Case

Here's the thing: Rolle's Theorem is just MVT with one extra condition. And once you understand this connection, both theorems click into place.

What if \( f(a) = f(b) \)?

Then the MVT formula simplifies dramatically:

$$f'(c) = \frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a} = \frac{0}{b - a} = 0$$

That's Rolle's Theorem. If the function starts and ends at the same value, there must be a point where the derivative equals zero—a horizontal tangent.

Rolle's Theorem (formal): If \( f(x) \) is continuous on \( [a, b] \), differentiable on \( (a, b) \), and \( f(a) = f(b) \), then there exists at least one \( c \) with \( a \leq c \leq b \) such that \( f'(c) = 0 \).

Historical note: The Indian mathematician Bhaskara II stated this theorem in the 12th century without formal proof. Michel Rolle provided the rigorous proof in 1691—about 500 years later.

Pro tip: You can use the calculator above for Rolle's Theorem problems too. Just enter values of \( a \) and \( b \) where \( f(a) = f(b) \), and the calculator will find where \( f'(c) = 0 \).

Don't confuse this with the Intermediate Value Theorem—that's a different beast entirely.

MVT vs. Rolle's Theorem: Quick Comparison

| Feature | Mean Value Theorem | Rolle's Theorem |

|---|---|---|

| Continuity requirement | Continuous on \( [a, b] \) | Continuous on \( [a, b] \) |

| Differentiability requirement | Differentiable on \( (a, b) \) | Differentiable on \( (a, b) \) |

| Endpoint condition | None | \( f(a) = f(b) \) |

| Conclusion | \( f'(c) = \frac{f(b)-f(a)}{b-a} \) | \( f'(c) = 0 \) |

| Geometric meaning | Tangent parallel to secant | Horizontal tangent exists |

Want to go deeper? Check out these 10 Best Selling Real Analysis Books covering the Mean Value Theorem, Rolle's Theorem, and much more.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the Mean Value Theorem used for?

The Mean Value Theorem is used to prove that a function achieves a specific rate of change at some point within an interval. Practical applications include proving speed limits were exceeded (if you traveled 100 miles in 1 hour, you must have hit 100 mph at some point), establishing bounds on function values, and proving other important calculus theorems.

What are the conditions for the Mean Value Theorem to apply?

Two conditions must be met: (1) The function must be continuous on the closed interval [a, b], meaning no breaks or jumps. (2) The function must be differentiable on the open interval (a, b), meaning the derivative exists at every interior point. If either condition fails, MVT may not apply.

How do I find the value of c in the Mean Value Theorem?

First, calculate the average rate of change: (f(b) - f(a))/(b - a). Then find the derivative f'(x) and set it equal to this average. Solve the equation f'(x) = (f(b) - f(a))/(b - a) for x. Any solution in the open interval (a, b) is a valid value of c. Use this calculator to find c values automatically.

What is the difference between Mean Value Theorem and Rolle's Theorem?

Rolle's Theorem is a special case of MVT where f(a) = f(b). In this case, the secant line is horizontal, so MVT guarantees a point c where f'(c) = 0. Think of Rolle's Theorem as MVT with the additional constraint that the function returns to its starting value.

Can there be more than one value of c that satisfies MVT?

Yes, absolutely. The theorem guarantees at least one such c exists, but there can be multiple values. For example, a cubic function on a large interval might have two or three points where the tangent line is parallel to the secant line. This calculator finds all such values within your specified interval.

What happens if the function is not differentiable at a point?

If the function has a corner, cusp, vertical tangent, or discontinuity within (a, b), the Mean Value Theorem does not apply. Common examples include |x| at x = 0 (corner) or x^(1/3) at x = 0 (vertical tangent). Always verify differentiability before applying MVT.

How is the Mean Value Theorem related to derivatives?

MVT connects average rate of change (the secant line slope) to instantaneous rate of change (the derivative). It guarantees that somewhere in the interval, these two rates are equal. This relationship is fundamental for proving many derivative properties and is used extensively in differential calculus proofs.

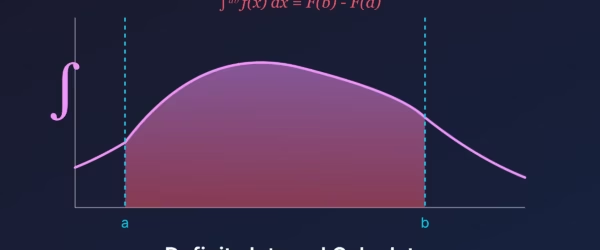

What is the geometric interpretation of the Mean Value Theorem?

Geometrically, MVT says that for any smooth curve connecting two points, there's at least one place where the tangent line is parallel to the line connecting the endpoints (the secant line). If you draw a line from (a, f(a)) to (b, f(b)), you can always find a point c where the curve has the same slope.

Can I use this calculator for Rolle's Theorem problems?

Yes! For Rolle's Theorem, enter any values of a and b where f(a) = f(b). The calculator will find all points c where f'(c) = 0. These are the horizontal tangent points that Rolle's Theorem guarantees must exist between your chosen endpoints.

Why does MVT require continuity on a closed interval but differentiability on an open interval?

Continuity at the endpoints a and b is needed to guarantee f(a) and f(b) exist and the function doesn't jump. However, differentiability at the endpoints isn't required because we only need a tangent line somewhere in the interior. A function can have corners at a or b and MVT still applies—as long as the interior is smooth.