Correlation vs Causation in SEO Experiments

- “We added more images and rankings improved. Images help SEO.”

- “Our pages with higher word count rank better. Long content wins.”

- “Sites that get mentioned on social media rank higher. Social signals are a ranking factor.”

All three statements commit the same logical error. They observe that A and B occur together and conclude that A causes B. It’s the most expensive mistake in SEO analysis, and it spreads through the industry like a virus because it sounds so reasonable.

I’ve seen agencies burn six-figure budgets optimizing for factors with zero causal impact. I’ve seen businesses chase strategies built entirely on misread data. And honestly, I’ve made these mistakes myself. Early in my career, I was certain social shares drove rankings because the correlation was so strong. It took me two years and a lot of wasted effort to understand what was actually happening.

The difference between correlation and causation isn’t academic. It’s the difference between strategies that work and strategies that only seem to work.

The Mathematical Distinction

Let’s be precise about what we’re talking about.

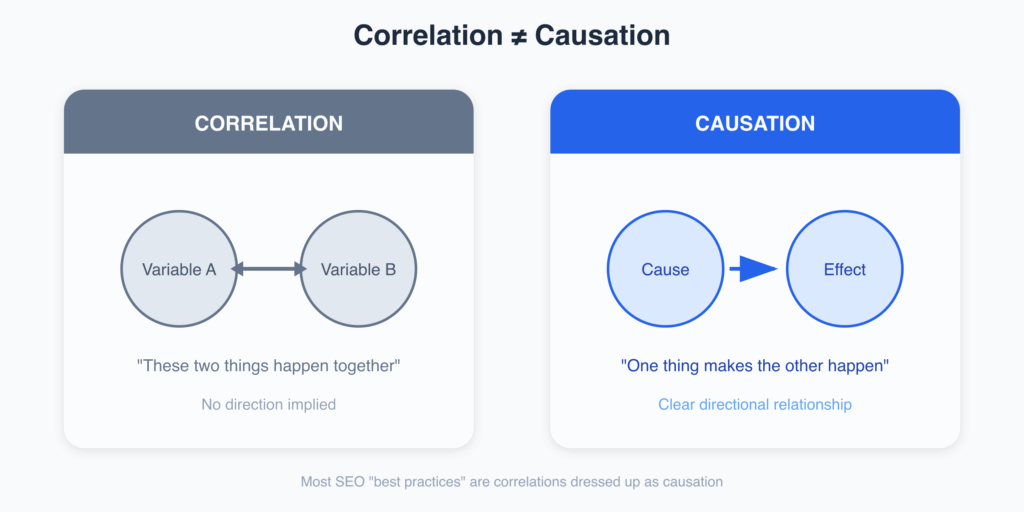

Correlation measures how two variables move together. When variable A increases and variable B also increases (or decreases), they’re correlated. The relationship might be strong or weak, positive or negative. But correlation alone tells you nothing about why they move together.

Causation means one variable actually produces a change in another. A directly influences B. Change A, and B changes as a result.

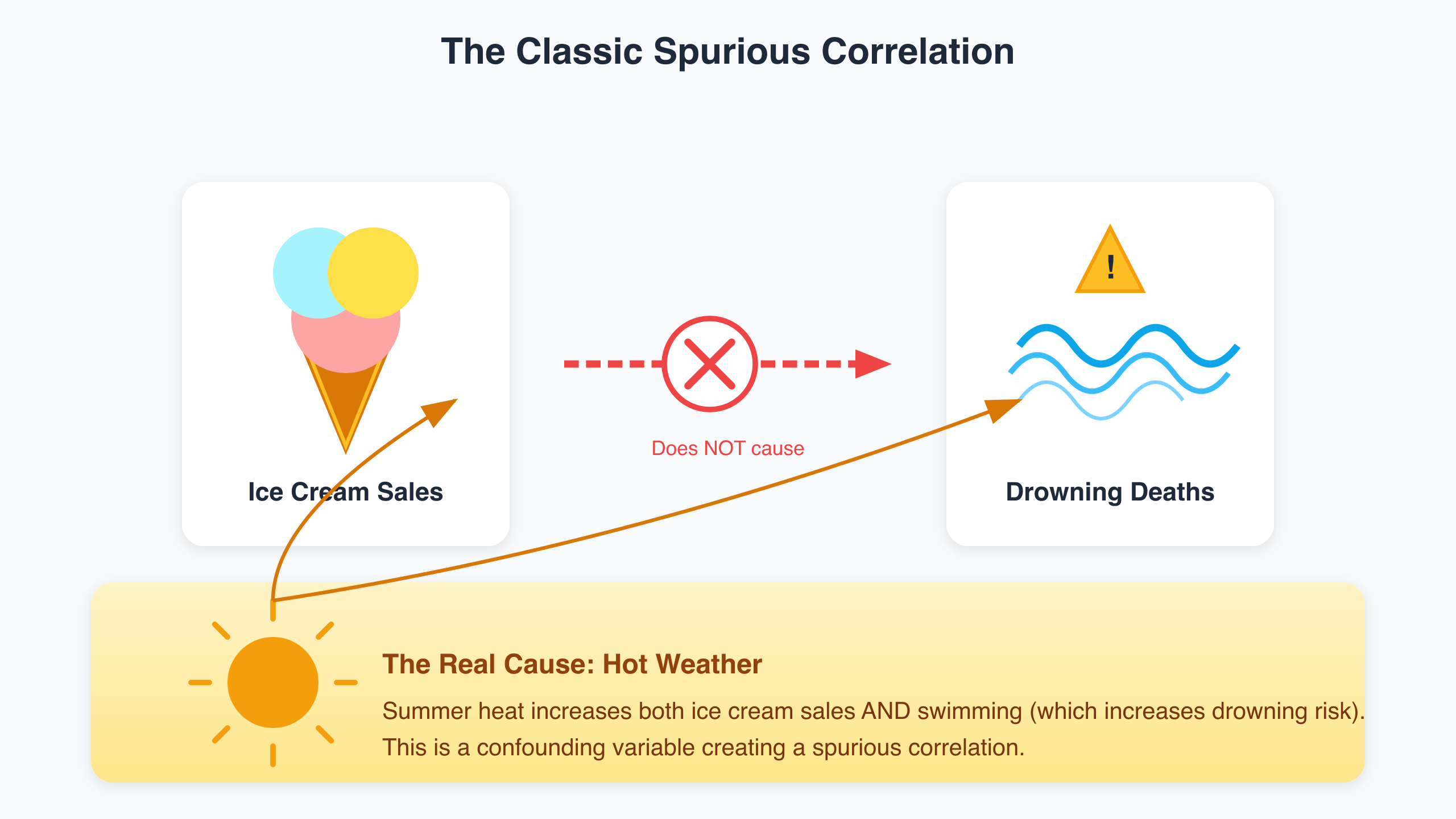

Here’s the classic example that makes this concrete. Ice cream sales and drowning deaths are strongly correlated. Both increase together every summer. But eating ice cream doesn’t cause drowning. Hot weather causes both. People buy more ice cream when it’s hot. People also swim more when it’s hot, which increases drowning risk. The correlation exists, but the causal mechanism people assume (ice cream → drowning) is completely wrong.

With ice cream and drowning, the error is obvious. With SEO data, it’s far less obvious. Pages with more backlinks rank higher. Correlation? Absolutely. Causation? Partially, yes. But here’s the complication: pages that rank higher also attract more backlinks because they’re visible. The causation runs in both directions, and separating the two effects is nearly impossible without controlled experiments.

This bidirectional causation is why so much SEO advice fails in practice. Someone observes that top-ranking pages have characteristic X. They conclude: do X to rank higher. But X might be a consequence of ranking, not a cause. Or X might correlate with ranking because both are caused by something else entirely.

SEO Correlation Traps I’ve Fallen Into

These are mistakes I see constantly. I’ve made most of them at some point, and some of them cost me real money and time before I figured out what was happening.

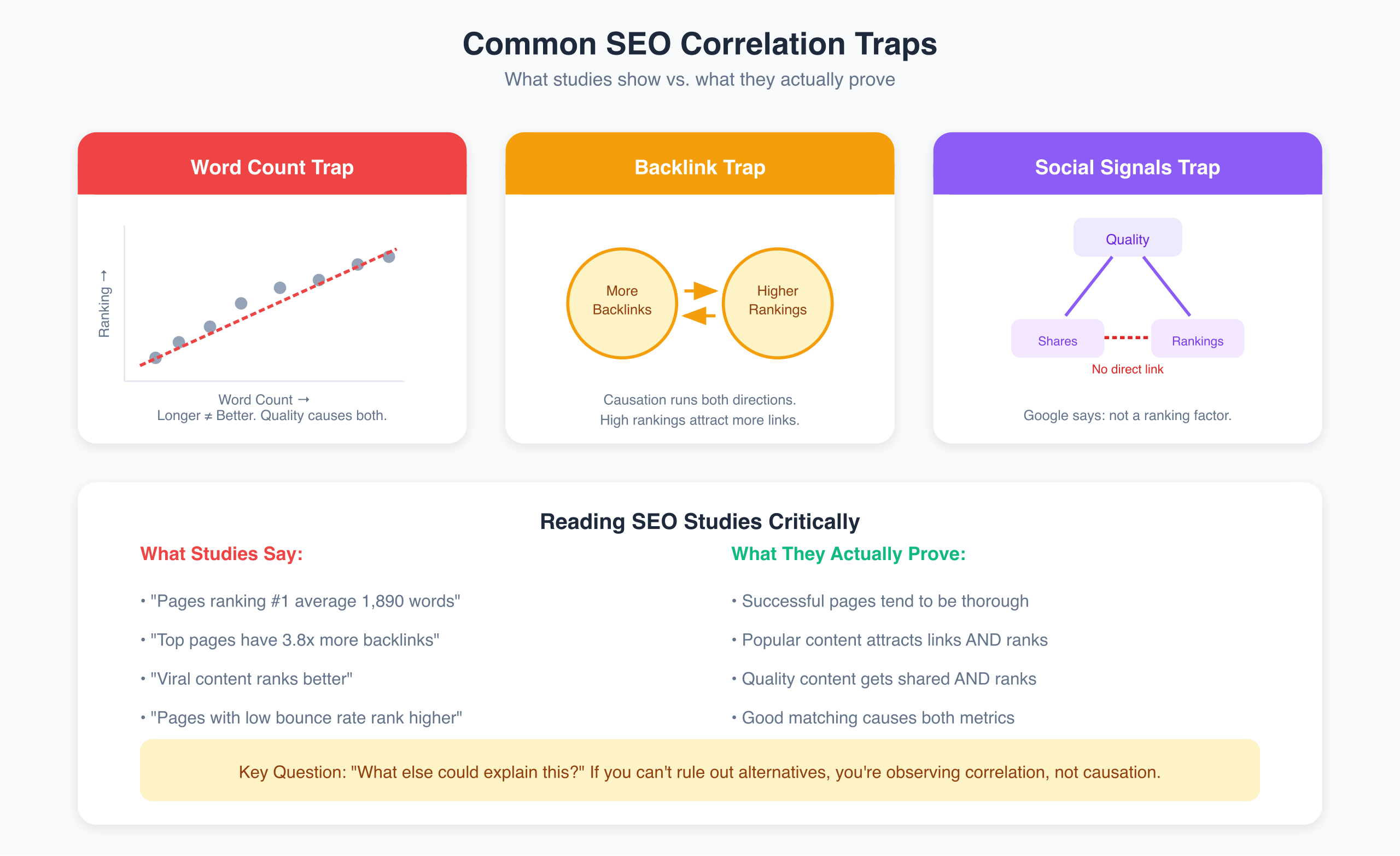

The Word Count Trap

You’ve seen the studies. Pages ranking #1 average 1,890 words. Or 2,450 words. The number changes depending on who’s doing the analysis, but the conclusion is always the same: write longer content.

But think about this more carefully. Maybe longer content ranks because it naturally covers topics more thoroughly. Maybe thorough content attracts more backlinks because there’s more substance to reference. Maybe it earns better engagement metrics because users find more value. Maybe the types of queries requiring comprehensive answers are fundamentally different from queries where 300 words suffice.

Or maybe the causation runs entirely the other direction. Content that’s good enough to rank #1 tends to be thorough. Thorough content tends to be longer. Length is a byproduct of quality, not a cause of ranking.

I’ve tested this directly. I have 500-word pages that outrank 5,000-word comprehensive guides on similar topics. The correlation exists in aggregate across millions of pages. It often fails completely in specific cases. That inconsistency is a red flag for weak or non-existent causation.

The Backlink Trap

Pages with more backlinks rank higher. Google has confirmed links matter. The mechanism (links as votes of confidence) makes intuitive sense. This is probably the strongest causal relationship we have in SEO.

But the relationship is bidirectional. Pages that rank higher get more visibility. More visibility attracts more links. High-ranking pages accumulate links because they rank, not just before they rank.

This matters because treating the correlation as purely one-directional leads to strategies that work differently for new pages than for established ones. The link-building approach for a page at position 50 isn’t the same as maintaining a page at position 1. If you only study what successful pages have without accounting for what they gained after success, your strategy will be miscalibrated.

The Engagement Metrics Trap

Pages with low bounce rates rank better. The intuitive conclusion: reduce bounce rate to improve rankings.

Google has repeatedly stated they don’t use bounce rate as a ranking factor. Yet the correlation exists. What’s happening?

Think about it from a different angle. Google shows pages that match user intent well. Pages that match intent have low bounce rates because users find what they’re looking for. The low bounce rate is a result of good intent matching, not a cause of ranking. Or consider that a third factor (content quality) causes both low bounce rates and high rankings. You’re observing correlation between two effects of the same hidden cause.

The Social Sharing Trap

This one got me for years. Viral content gets lots of social shares and ranks well. I was convinced social signals were a ranking factor despite Google saying otherwise. The correlation was too strong to ignore.

Eventually I figured out what was actually happening. Viral content attracts links. Those links help rankings. Viral content also gets mentioned in other articles and publications, creating even more links and brand exposure. Social sharing correlates with ranking because both are caused by content quality and promotion effort, not because one causes the other.

The shares didn’t cause the rankings. The underlying quality caused both.

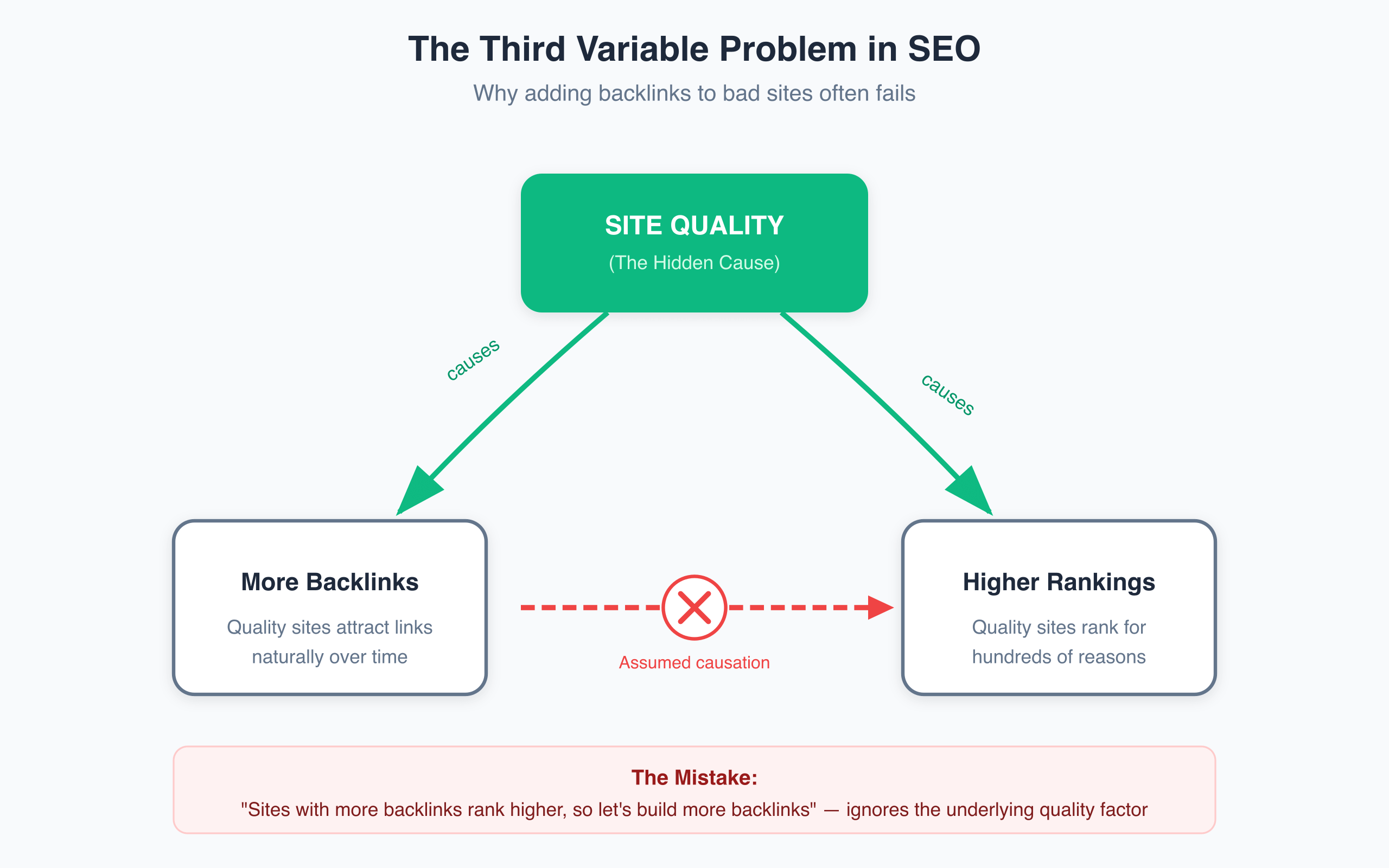

The Third Variable Problem

Most spurious correlations in SEO come from confounding variables. A third factor you didn’t measure causes both things you’re looking at.

High-quality sites tend to have more backlinks, better content, faster load times, lower bounce rates, and higher rankings. All of these metrics correlate with each other. If you compare any two of them, you’ll see a relationship. But is that relationship causal, or are you just measuring two symptoms of the same underlying condition?

This is why adding backlinks to a low-quality site often fails. The correlation between backlinks and rankings exists partly because quality sites attract both naturally. You can’t hack your way to high rankings by mimicking surface-level characteristics of successful sites without addressing the underlying quality factor.

The same logic applies to topic authority. Sites with expertise on a subject rank well. They also have more internal links on the topic, more related content, longer average articles. Studies might show any of these correlating with rankings. But the real cause is topical depth. Adding internal links without building genuine authority misses the point.

Brand strength works the same way. Established brands rank for competitive keywords. They also have faster sites, better design, more backlinks, higher CTR from search results. Which of these causes their rankings? All of them? None of them? Most likely, brand strength itself creates advantages that manifest across multiple metrics simultaneously.

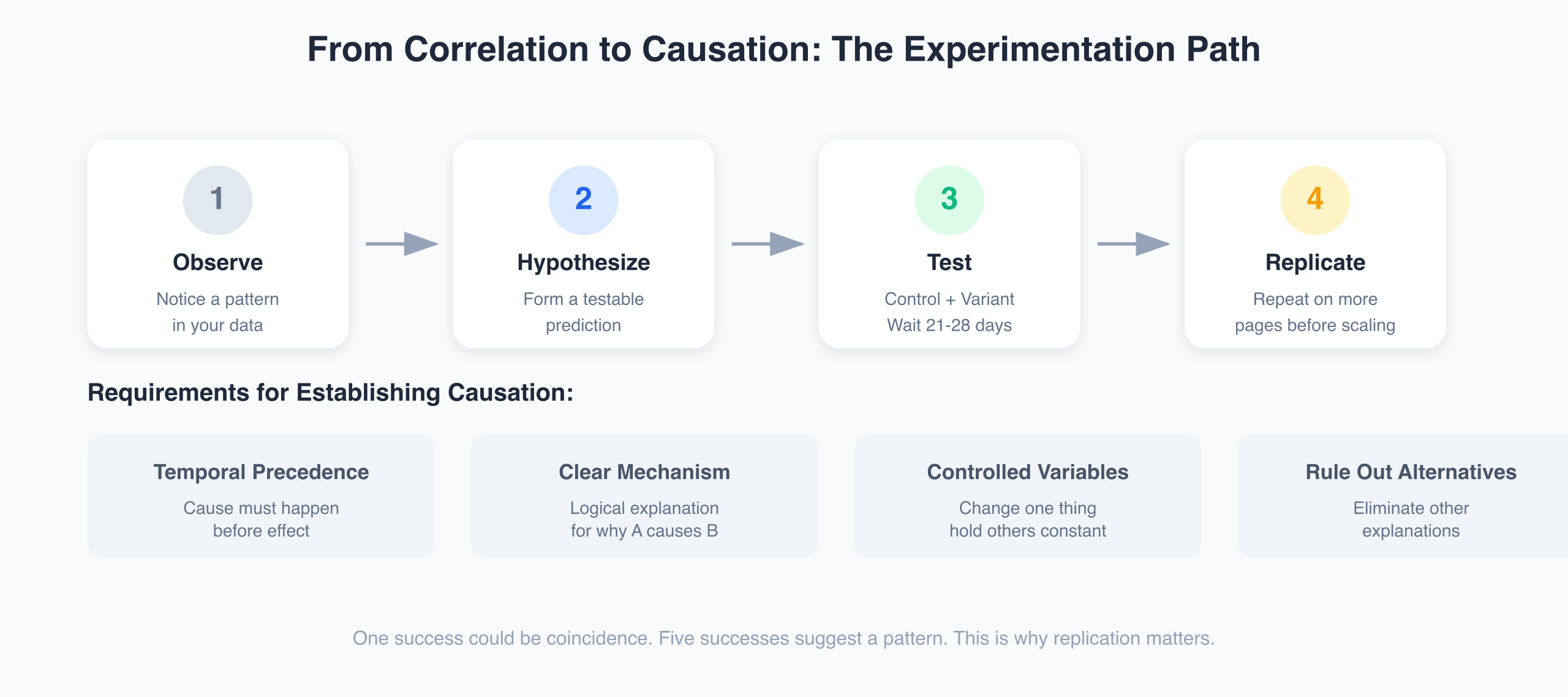

Establishing Causation Properly

Proving causation requires more than observing correlation. Here’s what you actually need.

Temporal Precedence

The cause must happen before the effect. If you add links and rankings improve later, that’s suggestive. If rankings were already improving before you got the links, links didn’t cause that specific improvement.

This sounds obvious but gets ignored constantly. “We implemented this change and rankings improved” proves nothing if rankings were trending up anyway. You need to establish the timeline precisely and account for pre-existing trends.

Clear Mechanism

There should be a logical explanation for why one thing causes another. Links as votes of confidence makes sense. Google can identify when sites reference other sites, and it’s reasonable that referenced content might be more valuable.

For unconfirmed factors, ask: why would this cause that? If you can’t explain the mechanism, be skeptical. “Social shares cause rankings” lacks a clear mechanism because Google can’t access most social platform data and has explicitly said they don’t use it.

Controlled Variables

The gold standard is controlled experimentation. Change one thing. Hold everything else constant. Measure what happens.

This is difficult in SEO because Google’s algorithm changes constantly, you can’t control every variable on a live site, sample sizes are often small, and results take weeks or months to manifest. But it’s not impossible. Split testing title tags, running experiments on similar pages, and before/after analysis with proper controls all help establish causation.

Ruling Out Alternatives

Can you explain the correlation another way? If you added images and rankings improved, maybe seasonal traffic patterns changed. Maybe a competitor dropped. Maybe you made other edits you forgot about. Maybe Google rolled out an algorithm update.

The more alternative explanations you can eliminate, the stronger your causal claim. If you can’t rule out alternatives, you’re observing correlation at best.

Practical SEO Experimentation in 2026

Testing causation in SEO has gotten more sophisticated. Here’s how to do it properly.

Understand the Different Test Types

Before-and-after studies are the weakest form of evidence. You change something, then observe what happens. No control group. No randomization. Any changes could be explained by external factors. These are common but nearly useless for establishing causation.

Single-case experiments improve slightly. You change one specific element on one page and track the impact. Better than nothing, but one success could easily be coincidence.

True SEO A/B testing is the gold standard. You randomize pages into control and variant groups, make changes only to variants, and compare results. This is fundamentally different from user A/B testing because you’re randomizing by page rather than by visitor.

Lab studies use test sites to examine specific technical behaviors in controlled environments. Useful for questions like “how does Google handle canonical tags in this situation?” Less useful for ranking factor questions.

Isolate Your Variables

Change one thing at a time. If you rewrite content, add images, update the title, and build links simultaneously, you’ll never know what helped. Maybe one change hurt while another helped, and they canceled out. You have no idea.

This is painful. It means slower optimization. But it’s the only way to know what actually works for your specific situation. Move fast and break things works for product development. It’s terrible for learning what actually drives rankings.

Build Proper Control Groups

Control groups are pages you leave completely unchanged. They represent your baseline. Variant groups get the specific change you’re testing. The comparison between them reveals whether your change had an effect.

Matching matters enormously. Control and variant pages should be similar in intent, template, traffic volume, and historical volatility. Poor matching destroys your ability to draw conclusions. If your control pages are fundamentally different from your variants, any difference in outcomes might be due to the page differences rather than your change.

Account for External Factors

Track algorithm updates during your test period. Monitor competitor changes. Note seasonal patterns. Document anything that might affect results beyond your experimental changes.

A ranking improvement means nothing if it coincided with a competitor’s site going down. A traffic drop might be December seasonality, not your changes. Keep detailed logs. Tools like Semrush track algorithm volatility and competitor movements that help explain your results.

Replicate Before Scaling

If changing something helped one page, try it on another. And another. If it works consistently across multiple pages with different characteristics, causation becomes much more likely.

One success could be noise. Five successes suggest a pattern. Ten successes across different page types is strong evidence. This is why single-case experiments are weak. You need replication before drawing conclusions you’ll act on at scale.

Wait Long Enough

SEO changes take time to manifest. A one-week test might show nothing even if the change would help over time. Google needs to recrawl, reindex, and reprocess. Rankings fluctuate naturally and need time to stabilize.

Most SEO tests need at least 21-28 days minimum. Tests for competitive terms need longer. Sites with lower traffic need even longer to reach statistical significance. Patience is part of the methodology. Impatient conclusions are usually wrong conclusions.

Real-World Experiment Examples

Here are some actual controlled SEO experiments that demonstrate proper methodology.

SearchPilot tested Google’s auto-generated descriptions versus custom meta descriptions. They used the data-nosnippet attribute on half their test pages to force Google to generate descriptions, while the other half used custom metas. Within two weeks, click-through rates for Google-generated descriptions were about 3% lower than custom descriptions. Statistical significance confirmed the difference was real, not random variation.

This is genuine causal evidence. Controlled conditions. Randomized assignment. Measurable outcome. The meta description choice caused the CTR difference.

SearchPilot also tested visible content versus content hidden in tabs. Pages with fully visible text received 12% more organic sessions than versions with content in expandable tabs. The controlled experiment established causation. Google treats hidden content differently, or users engage differently with visible content. Either way, the experimental design allowed causal inference.

Reboot Online ran a 3-month controlled experiment comparing AI-written and human-written content. Same site structure. Same link building. Same everything except content creation method. Human content performed better. But the valuable insight isn’t the specific result. It’s that by controlling all other variables, they could isolate the content creation factor and make a causal claim.

Reading SEO Studies Critically

Most published SEO research is correlation research. Read it with appropriate skepticism.

“Pages ranking #1 have X characteristic” tells you what successful pages look like. It doesn’t tell you what made them successful. It’s descriptive, not prescriptive. Top-ranking pages might have certain features as a consequence of their success, not as a cause of it.

“We analyzed 1 million pages and found…” sounds impressive, but large sample sizes don’t eliminate confounding variables. They might even amplify misleading correlations by making spurious relationships look statistically significant. A million pages might all share a confounding variable you didn’t measure. Sample size doesn’t fix that problem.

“After implementing X, rankings improved” proves nothing in isolation. What else changed? Was there a control group? How long was the observation period? Did competitors or Google’s algorithm change during that time? Without answers to these questions, you’re looking at observational evidence that suggests further investigation, not confident conclusions.

“Our data shows X causes Y” is a red flag. Look at the methodology. Were variables controlled? Was there randomization? Did they actually test causation or just observe correlation? Most studies claiming causation are actually showing correlation with sloppy language. Don’t be fooled by confident phrasing.

What We Actually Know

Some SEO causation is well-established through extensive evidence, Google confirmation, and consistent experimental replication.

Quality backlinks help rankings. Extensive evidence. Google confirms. Mechanism makes sense. Experiments consistently show impact. This is as close to proven causation as we get.

Relevant, comprehensive content helps. Matches Google’s stated goals. Correlates strongly in studies. Replicates experimentally. The relationship is causal, though exactly how Google measures “comprehensive” remains unclear.

Technical problems hurt. Slow sites, crawl errors, broken pages, and indexing issues demonstrably hurt rankings. Fix the problem, rankings recover. Testable and consistent.

Title tags affect click-through rates. Directly testable. Changes to titles change CTR. The mechanism is obvious: users read titles and decide whether to click.

Much else remains genuinely uncertain:

Content length impact: Correlation is strong. Independent causation is unclear. Thorough content helps. Whether word count itself matters beyond thoroughness is debatable.

Engagement metrics: Google says they’re not direct ranking factors. Correlations exist. Confounding variables likely explain much of the relationship.

Social signals: Correlation with rankings exists. Direct causation is denied by Google. Indirect effects through links and brand awareness are likely explanations.

Many on-page factors: We know they matter in aggregate. We don’t know exact weights or precise mechanisms. Experiments help, but the algorithm is genuinely complex.

Building an Experimental Mindset

Good SEO analysis requires intellectual humility and systematic thinking. Here’s how I approach it now, after years of making correlation-based mistakes.

Hold conclusions loosely. You don’t know everything. Nobody does. Google’s algorithm has hundreds of interacting factors. Even Google engineers don’t fully understand how changes propagate through the system. Certainty is usually a sign you haven’t thought hard enough about alternatives.

Treat correlations as questions, not answers. When you observe that A and B occur together, your next step is designing an experiment to test causation. Not implementing a strategy based on unproven assumptions.

Test before scaling. If you’re planning to change 100 pages based on a hypothesis, test on 10 first. With controls. If the test fails, you saved 90 pages from useless changes. If it succeeds, you have evidence to justify scaling.

Document everything. Keep logs of changes, timing, external factors, and results. Six months later, you won’t remember what you changed when. Documentation enables learning from your own experiments.

Update beliefs when evidence contradicts them. Stubbornly defending disproven assumptions is expensive. When experiments show your hypothesis was wrong, update your mental model. That’s how you get better at this.

Build testing into your process. Don’t treat experiments as special projects. Every significant change should be testable. Make experimentation part of how you do SEO, not an occasional add-on.

Common Experimental Failures

Even with good intentions, experiments fail. I’ve made all of these mistakes.

No control group. “We changed all our title tags and traffic increased.” Compared to what? Maybe traffic would have increased anyway due to seasonal patterns or algorithm changes.

Too many variables. You changed title, added content, updated images, and built links. Rankings improved. Which change helped? All of them? None of them? Some helped while others hurt? You can’t know.

Too short duration. One week isn’t enough. Google’s indexing and ranking process takes time. Wait at least 3-4 weeks. Competitive queries need longer.

Too small sample. One page isn’t enough to establish patterns. You need multiple pages to separate signal from noise.

Ignored external factors. An algorithm update happened during your test. A major competitor launched a campaign. Your results are contaminated by factors you didn’t account for.

Confirmation bias. You wanted the test to succeed, so you interpreted ambiguous results as success. Be honest about uncertain outcomes. “Inconclusive” is a valid result.

No replication. It worked once. Will it work again? Test on more pages before deciding it’s a reliable strategy.

Tools for SEO Experimentation

Several tools make controlled SEO experimentation practical.

SearchPilot offers enterprise-level SEO A/B testing. Expensive, but methodologically sound. Worth it for large sites that need rigorous testing at scale.

Google Search Console provides before-and-after data for any changes you make. Not controlled experimentation, but essential for tracking outcomes.

Semrush or Ahrefs track rankings, competitors, and algorithm updates. Essential context for interpreting experimental results. You need to know what else was happening when your metrics changed.

Spreadsheets for documenting changes, timelines, and results. I use Notion databases for this. Not glamorous but essential. The tools matter less than the discipline of recording everything.

Statistical tools for determining significance. Google Sheets can handle basic statistical tests. More sophisticated experiments might need proper statistical software, but don’t let tool complexity stop you from starting with basics.

The Bottom Line

Confusing correlation with causation leads to confident wrongness. Understanding the difference leads to effective experimentation and genuine learning.

Most SEO advice is based on correlation. Most “best practices” are untested assumptions dressed up as facts. The industry is full of confident statements built on shaky evidence. That’s not cynicism. It’s observation.

The best SEOs I know hold their conclusions loosely. They’re always testing, always questioning, always updating their understanding. They don’t confuse what successful pages look like with what made them successful.

You don’t need to test everything from scratch. Some things are established. Links help. Good content helps. Technical problems hurt. But for anything else, especially anything that sounds clever or counterintuitive, be skeptical until you’ve tested it yourself in your specific context.

Run experiments. Use controls. Wait long enough. Replicate results. That’s how you move from correlation to causation, from guessing to knowing, from following industry myths to understanding what actually works.

FAQs

What’s the difference between correlation and causation in SEO?

Correlation means two variables move together. Causation means one variable directly produces a change in another. High-ranking pages have more backlinks (correlation). But do backlinks cause high rankings, or do high rankings attract backlinks? Often both, or a third factor causes both. Most SEO mistakes come from treating correlation as causation without controlled testing.

Does longer content actually cause better rankings?

Studies show correlation between word count and rankings. But longer content might rank because it’s more comprehensive, attracts more links, or earns better engagement. Length is likely a byproduct of quality rather than an independent cause. Thorough content helps. Whether word count itself matters independently is debatable and mostly untested in controlled conditions.

How do I run a proper SEO A/B test?

Split pages into control and variant groups matched by intent, template, and traffic level. Change only one variable on variant pages. Wait at least 21-28 days for results. Track external factors like algorithm updates. Compare performance between groups. Replicate on additional pages before scaling. SEO A/B testing randomizes by page rather than by visitor, which is different from traditional web A/B testing.

What is the third variable problem in SEO studies?

A confounding variable causes both things you’re measuring, creating an illusion of causation. High-quality sites have more backlinks AND higher rankings. The correlation between backlinks and rankings might exist partly because quality causes both, not purely because backlinks cause rankings. This is why adding backlinks to low-quality sites often fails despite strong correlation in aggregate studies.

How should I read SEO studies critically?

Ask: were variables controlled? Was there randomization? Is this correlation or tested causation? What else could explain this finding? Large sample sizes don’t eliminate confounding variables. ‘Pages ranking #1 have X’ tells you what successful pages look like, not what made them successful. Most SEO studies are descriptive, not prescriptive, regardless of how confidently they’re written.

What SEO factors have proven causation?

Quality backlinks, relevant comprehensive content, and technical performance have strong causal evidence through experiments and Google confirmation. Title tags cause CTR changes (directly testable). Much else is genuinely uncertain: content length, engagement metrics, social signals, and many on-page factors show correlation but unclear causation. Test before assuming any unconfirmed factor matters for your specific situation.

Disclaimer: This site is reader‑supported. If you buy through some links, I may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. I only recommend tools I trust and would use myself. Your support helps keep gauravtiwari.org free and focused on real-world advice. Thanks. — Gaurav Tiwari