Raman Effect – Biography of CV Raman, Theory and Examples

This is a complete guide to the Raman Effect, covering CV Raman’s life, the theory behind Raman Scattering, and practical applications of Raman Spectroscopy.

If you’re a physics student (graduate or undergraduate), this article will give you everything you need to understand Raman’s groundbreaking work. We’ll cover the history, the classical theory with full derivations, and why this discovery still matters today.

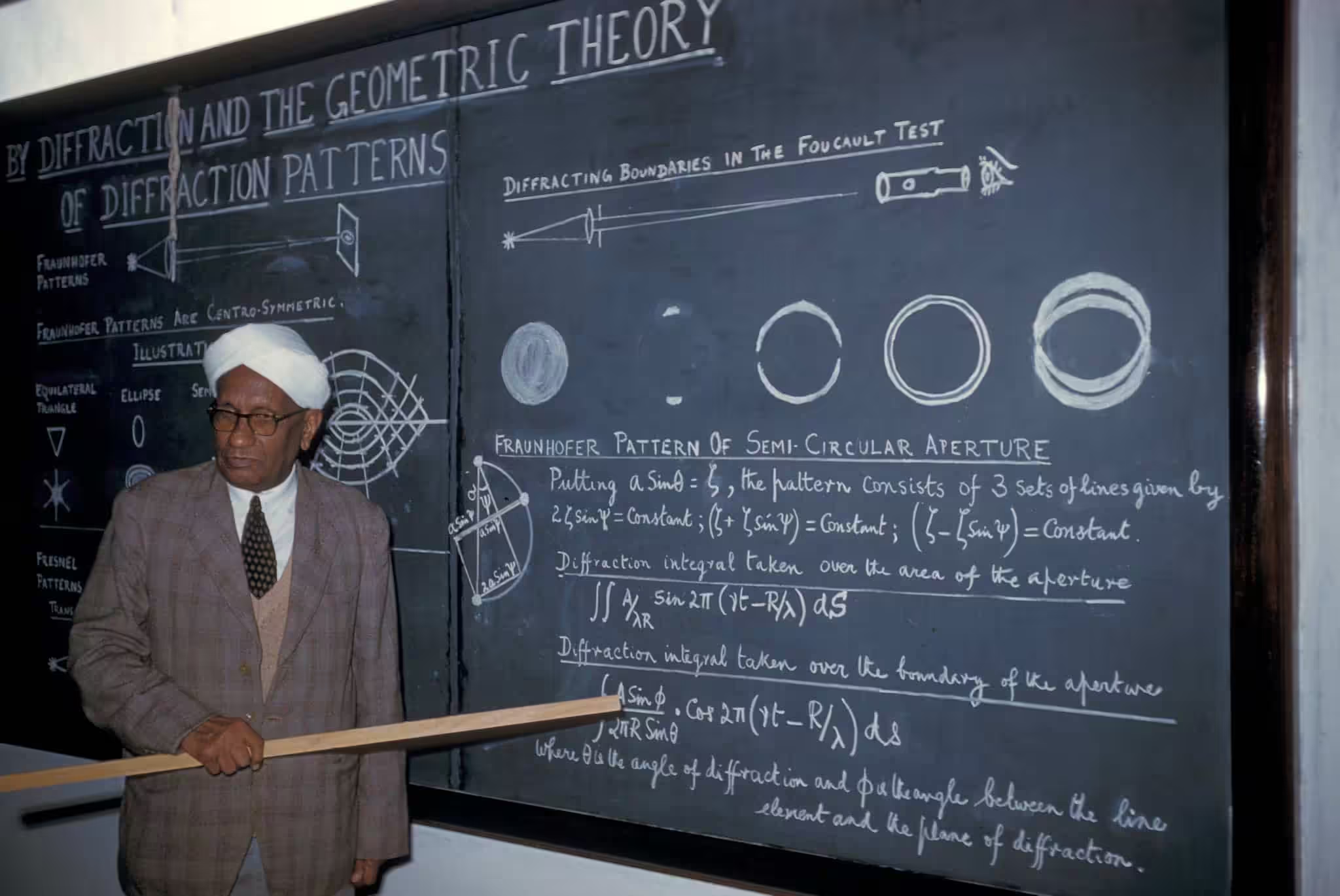

About CV Raman

Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman (known as CV Raman) was an Indian physicist, mathematician, and Nobel laureate. His first name was Venkata. He was a Tamil Brahmin and the second of eight children.

Raman was born on 7th November 1888 at Thiruvanaikaval, near Tiruchirappalli in what was then Madras Presidency (now Tamil Nadu). His father lectured in mathematics and physics, which sparked Raman’s early interest in science.

Here’s how his remarkable career unfolded:

- Raman moved to Visakhapatnam at a young age, where he studied at St. Aloysius Anglo-Indian High School.

- After graduating, he joined the Indian government’s finance department. But his passion for physics never faded.

- In 1917, at just 28 years old, Raman resigned from government service to become the Palit Professor of Physics at the University of Calcutta.

- On 28th February 1928, Raman announced his discovery of the Raman Effect through his experiments on light scattering. This date is now celebrated as National Science Day in India.

- In 1930, Raman received the Nobel Prize in Physics for this discovery, becoming the first Asian to win a Nobel Prize in science.

- In 1932, Raman and S. Bhagavantam discovered the quantum photon spin, further confirming the quantum nature of light.

History of the Raman Effect

Before 1928, scientists had to use infrared spectroscopy to study the vibrational and rotational properties of molecules. This was inconvenient and limited in scope. Raman’s discovery changed everything. Suddenly, researchers could excite molecules using visible light and study their properties with far greater ease.

The theoretical groundwork for the Raman Effect was laid before Raman’s experiments. Adolf Smekal predicted inelastic light scattering in 1923. Kramers and Heisenberg expanded on this work in 1925, followed by Dirac in 1927. But it was Raman and his student K.S. Krishnan who first observed experimental evidence of inelastic scattering in liquids in 1928.

Raman immediately recognized he was dealing with something fundamental. The phenomenon was analogous to the Compton Effect (where X-rays scatter off electrons with a change in wavelength), but this was happening with visible light and molecules.

To confirm his discovery, Raman used a mercury arc lamp and a spectrograph to record the spectrum of scattered light.

What Raman observed was striking. When any transparent substance (solid, liquid, or gas) was illuminated by the mercury arc, the scattered light contained more than just the original frequencies. The spectrum showed new lines, bands, and continuous radiation shifted from the incident frequencies. The unmodified radiation was Rayleigh scattering. The modified radiation was something new entirely.

What is the Raman Effect?

The Raman Effect is the change in wavelength of light when a light beam is deflected by molecules.

When a beam of light passes through a transparent, dust-free sample, most of the light continues in its original direction. But a small portion scatters in other directions. Most of this scattered light has the same wavelength as the incident beam. However, a tiny fraction has a different wavelength. This wavelength shift is the Raman Effect.

Think of it this way. When photons from the light source collide with molecules in the sample, most collisions are elastic. The photons bounce off with the same energy and frequency they had before. But occasionally, a collision is inelastic. The molecule either absorbs energy from the photon or gives energy to it. The scattered photon leaves with a different frequency.

These frequency changes tell us about the energy transitions happening inside the molecule. They reveal information about vibrational and rotational states that would otherwise be difficult to measure.

The Raman Effect is weak. For a typical liquid, the intensity of the modified light might be only 1/100,000th of the incident beam. But every molecule produces a characteristic pattern of Raman lines, with intensity proportional to the number of scattering molecules. This makes Raman spectroscopy useful for both qualitative and quantitative analysis.

The energies corresponding to Raman frequency shifts match the energies of vibrational and rotational transitions within molecules. For simple gaseous molecules, you can observe pure rotational shifts. In liquids, molecular rotation is hindered, so you won’t see discrete rotational Raman lines. The Raman Effect primarily reveals vibrational transitions, which produce observable shifts in solids, liquids, and gases alike.

Gases at ordinary temperatures have low molecular concentration and produce weak Raman effects. That’s why most Raman spectroscopy work focuses on solids and liquids.

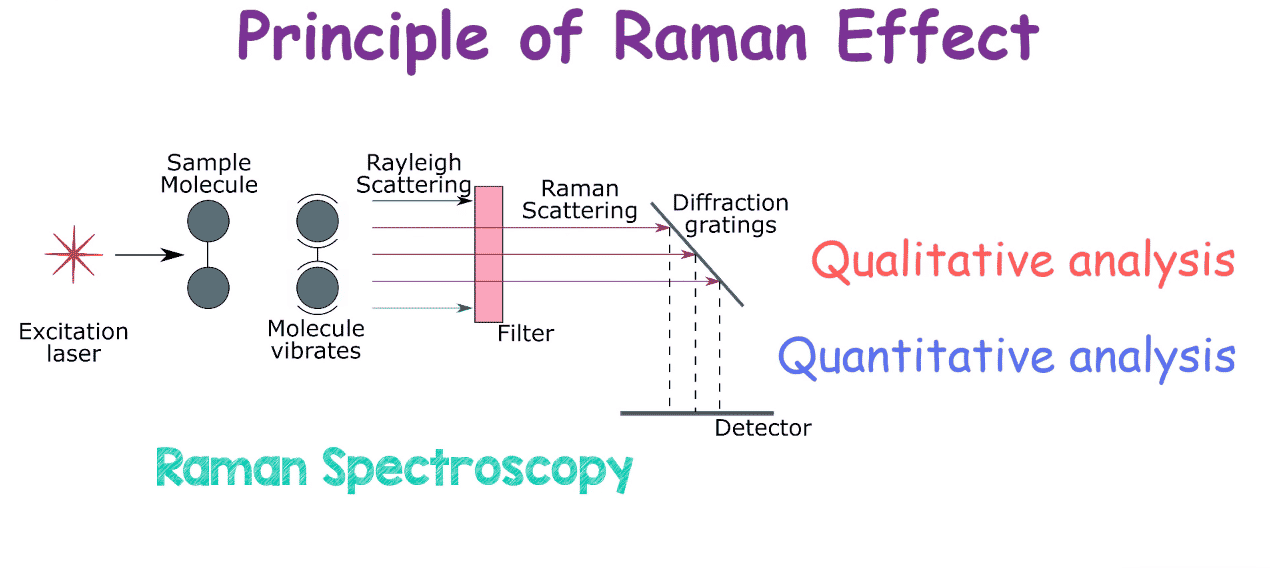

Raman Spectroscopy

Definition: Spectroscopy is the study of how electromagnetic radiation interacts with matter. The goal is to determine the nature of the material being studied. The intensity of radiation as a function of wavelength, frequency, or energy is called the “spectrum.”

Unlike other forms of spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy doesn’t measure light absorption. It measures light scattering. This distinction makes it uniquely powerful for certain applications.

Raman Scattering Explained

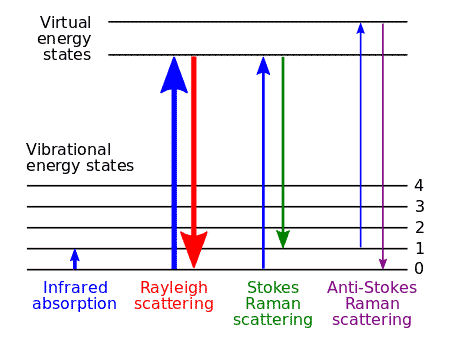

When light of a specific frequency passes through any substance (gas, liquid, or solid), the scattered light contains more than just the original frequency. Raman discovered that light scattered at right angles includes frequencies that are generally lower (sometimes higher) than the incident light.

This phenomenon is Raman Scattering. The scattered lines with lower frequencies are called Stokes lines. Those with higher frequencies are anti-Stokes lines.

If \( f \) is the frequency of incident light and \( f’ \) is the frequency of a scattered line, then \( f – f’ \) is the Raman Frequency. This frequency difference doesn’t depend on the incident light frequency. It’s a constant that characterizes the substance itself.

A remarkable feature of Raman Scattering is that Raman Frequencies match (within experimental error) the frequencies obtained from infrared rotation-vibration spectra of the same substance.

Physically, Raman scattering occurs because of inelastic collisions between photons and electrons. The energy difference between incident and scattered photons generates the Raman lines.

Advantages of Raman Spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy offers several advantages over infrared spectroscopy:

- It works for gases, liquids, and solids. Infrared spectra of liquids and solids are often too diffuse to be quantitatively useful.

- Non-polar molecules like \( \text{O}_2 \), \( \text{N}_2 \), and \( \text{Cl}_2 \) show Raman scattering even though they don’t appear in infrared spectra. This is because Raman activity requires a change in polarizability, not a permanent dipole moment.

- Rotation-vibration changes in non-polar molecules can only be observed through Raman spectroscopy.

- Raman frequencies are only slightly different from incident frequencies. By choosing appropriate incident radiation, you can bring the scattered lines into the visible region where measurement is easier. Infrared measurements are far more challenging.

- It uses visible or ultraviolet radiation instead of infrared, which simplifies the experimental setup.

Applications of Raman Spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy has found applications across multiple fields:

- Investigating biological systems, including polypeptides and proteins in aqueous solutions. Water doesn’t interfere with Raman measurements the way it does with infrared.

- Determining molecular structures. The Raman spectrum provides a “fingerprint” of the molecule.

- Pharmaceutical analysis, where it’s used to identify compounds and verify drug purity.

- Materials science, including the characterization of carbon nanotubes and graphene.

- Art conservation and forensics, where non-destructive analysis of samples is critical.

Classical Theory of Raman Effect

The classical theory of the Raman Effect (also called the polarizability theory) was developed by George Placzek in 1934. It provides an elegant explanation for why Raman scattering occurs.

The basic idea is this: when a photon interacts with a molecule, it causes the electrons and nuclei to move, inducing an oscillating electric dipole. This dipole then radiates photons, some of which have different frequencies from the incident light.

The electric field \( E \) of electromagnetic radiation induces a dipole moment \( \mu \) in a molecule:

$$ \mu = \alpha E \quad \text{…(1)} $$

Here, \( \alpha \) is the polarizability of the molecule. The electric field oscillates as:

$$ E = E_0 \sin \omega t = E_0 \sin 2\pi \nu t \quad \text{…(2)} $$

where \( E_0 \) is the amplitude and \( \nu \) is the frequency of the incident light.

Substituting equation (2) into equation (1):

$$ \mu = \alpha E_0 \sin 2\pi \nu t \quad \text{…(3)} $$

An oscillating dipole at frequency \( \nu \) radiates light at that same frequency. This is Rayleigh scattering. But here’s where it gets interesting.

If the polarizability changes during molecular vibration, we can write:

$$ \alpha = \alpha_0 + \frac{d\alpha}{dq} q \quad \text{…(4)} $$

where \( q \) describes the molecular vibration coordinate. The vibration itself oscillates as:

$$ q = q_0 \sin 2\pi \nu_m t \quad \text{…(5)} $$

Here, \( q_0 \) is the amplitude and \( \nu_m \) is the molecular vibration frequency.

Combining equations (4) and (5):

$$ \alpha = \alpha_0 + \frac{d\alpha}{dq} q_0 \sin 2\pi \nu_m t \quad \text{…(6)} $$

Substituting this into equation (3):

$$ \mu = \alpha_0 E_0 \sin 2\pi \nu t + \frac{d\alpha}{dq} q_0 E_0 \sin 2\pi \nu t \sin 2\pi \nu_m t \quad \text{…(7)} $$

Using the trigonometric identity \( \sin x \sin y = \frac{1}{2}[\cos(x-y) – \cos(x+y)] \), this becomes:

$$ \mu = \alpha_0 E_0 \sin 2\pi \nu t + \frac{1}{2} \frac{d\alpha}{dq} q_0 E_0 \left[ \cos 2\pi(\nu – \nu_m)t – \cos 2\pi(\nu + \nu_m)t \right] \quad \text{…(8)} $$

This result shows that the oscillating dipole has three frequency components:

- The incident frequency \( \nu \) with amplitude \( \alpha_0 E_0 \) (Rayleigh scattering)

- The frequency \( \nu – \nu_m \) (Stokes line)

- The frequency \( \nu + \nu_m \) (Anti-Stokes line)

The Stokes and anti-Stokes lines have much smaller amplitudes of \( \frac{1}{2} \frac{d\alpha}{dq} q_0 E_0 \), which explains why Raman scattering is so much weaker than Rayleigh scattering.

If the molecular vibration doesn’t change the polarizability (meaning \( \frac{d\alpha}{dq} = 0 \)), then the dipole oscillates only at the incident frequency. No Raman scattering occurs.

This gives us the selection rule for Raman activity: for a vibration or rotation to be Raman-active, it must cause a change in molecular polarizability:

$$ \frac{d\alpha}{dq} \neq 0 \quad \text{…(9)} $$

This is why homonuclear diatomic molecules like \( \text{H}_2 \), \( \text{N}_2 \), and \( \text{O}_2 \) show Raman spectra but no infrared spectra. They lack permanent dipole moments (so no IR absorption), but their vibrations do change polarizability (so Raman scattering occurs). The changing polarizability induces a changing dipole moment at the vibrational frequency, which radiates the Raman-shifted light.

Further Reading

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was CV Raman?

Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman was an Indian physicist and mathematician who won the 1930 Nobel Prize in Physics. He discovered the Raman Effect, which describes how light changes wavelength when scattered by molecules.

What was CV Raman’s first name?

Venkata was his first name. “CV Raman” stands for Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman.

When was CV Raman born?

He was born on 7th November 1888 at Thiruvanaikaval, near Tiruchirappalli in the Madras Presidency (now Tamil Nadu, India).

When did CV Raman receive the Nobel Prize?

Raman received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1930 for his work on light scattering and the discovery of the Raman Effect. He was the first Asian scientist to win a Nobel Prize in any science field.

Why is National Science Day celebrated on 28th February?

National Science Day commemorates the announcement of the Raman Effect on 28th February 1928. It marks the day Raman publicly revealed his discovery, not his birthday (which was 7th November).

What is the Raman Effect?

The Raman Effect is the change in wavelength of light when it’s scattered by molecules. Most scattered light keeps the same wavelength (Rayleigh scattering), but a small fraction shifts to different wavelengths. This shift reveals information about molecular vibrations and rotations.

What is spectroscopy?

Spectroscopy is the study of how electromagnetic radiation interacts with matter. Scientists use it to identify substances and understand their properties by analyzing the spectrum of absorbed, emitted, or scattered radiation.

What is the polarizability theory?

The polarizability theory is the classical explanation for the Raman Effect, developed by George Placzek in 1934. It explains that Raman scattering occurs when molecular vibrations cause changes in the molecule’s polarizability, inducing oscillating dipoles that radiate at shifted frequencies.

What are Stokes and anti-Stokes lines?

Stokes lines are scattered light with lower frequency (longer wavelength) than the incident light. The molecule absorbs energy from the photon. Anti-Stokes lines have higher frequency (shorter wavelength) because the molecule gives energy to the photon. At room temperature, Stokes lines are more intense because more molecules start in the ground vibrational state.

sir super, thanks you so much

thank you sir , your effort gives me life to my dreame,

The #BirthAnniversary of one of the most prominent #Indian #scientists in history, Sir #CVRaman was on 07th Nov. Let us all pay a #heartfelt #tribute to him on cvraman.tributes.in.

He was the first Indian person to win the Nobel Prize in science for his illustrious 1930 discovery, which is known as the “Raman Effect”.

In case you wish to create a tribute for your loved ones as well, please give us a missed call on +91-9643105042.

Our associates will get in touch with you.

You can also create a profile yourself on – tributes.in

https://cvraman.tributes.in

Great article! Thanks for sharing.

Thanks for sharing this. I am a Non-medical student at Panjab University. IIn Bsc there is topic on Raman effect. you had explain the topic very well.

Good job amazing explanation

Thanks for sharing this. I am a Non-medical student at Panjab University. IIn Bsc there is topic on Raman effect. you had explain the topic very well.

I am not very wonderful with English but I get hold this very easy to interpret.