Euler’s (Prime to) Prime Generating Equation

Leonhard Euler discovered something that shouldn’t work. A simple formula that spits out prime numbers. Not just a few of them. Forty consecutive primes from a single quadratic equation.

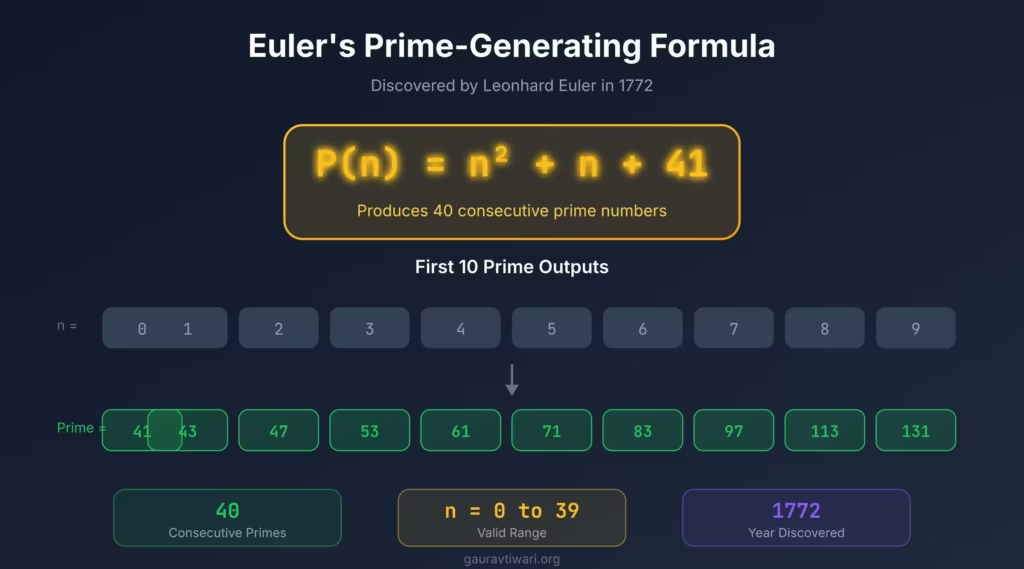

The formula is deceptively simple: n² + n + 41. Plug in 0, you get 41. Plug in 1, you get 43. Keep going through n = 39, and every single result is prime. I’ve run through this myself, and watching the pattern hold is genuinely satisfying.

But here’s where it gets interesting. At n = 40, the magic breaks. And the reason why it breaks reveals something deep about the structure of numbers themselves.

The Formula That Generates 40 Primes

Euler presented this formula in 1772, and mathematicians have been fascinated by it ever since. The expression P(n) = n² + n + 41 produces prime numbers for all integers from 0 to 39. That’s not a typo. One formula, forty primes in a row.

Let me show you the first several values:

| n | n² + n + 41 | Prime? |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 41 | Yes |

| 1 | 43 | Yes |

| 2 | 47 | Yes |

| 3 | 53 | Yes |

| 4 | 61 | Yes |

| 5 | 71 | Yes |

| 6 | 83 | Yes |

| 7 | 97 | Yes |

| 8 | 113 | Yes |

| 9 | 131 | Yes |

| 10 | 151 | Yes |

The pattern continues all the way to n = 39, where the formula produces 1601. Still prime. But something changes at n = 40.

Why the Formula Fails at n = 40

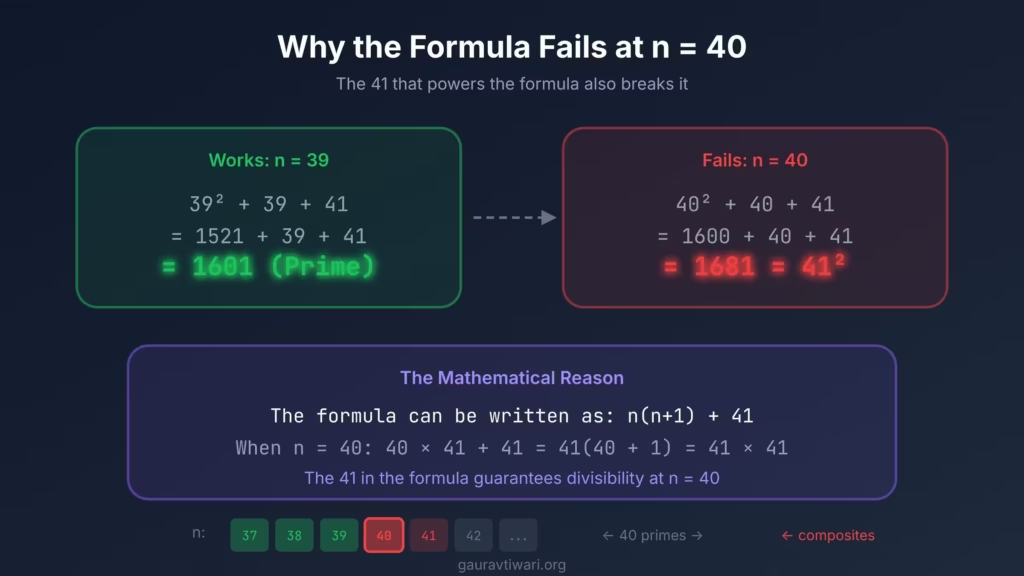

At n = 40, the formula gives us 40² + 40 + 41 = 1600 + 40 + 41 = 1681. And 1681 = 41 × 41 = 41². The number 41 that made this formula work for so long finally catches up and divides the result.

This isn’t a coincidence. The formula can be rewritten as n(n + 1) + 41. When n = 40, you get 40 × 41 + 41 = 41(40 + 1) = 41 × 41. The 41 that sits in the formula guarantees it will divide evenly when n reaches 40.

Similarly, at n = 41, you get 41² + 41 + 41 = 41(41 + 1 + 1) = 41 × 43. Again divisible by 41. The magic number that gave the formula its power is also the reason it must eventually fail.

Negative Values Work Too

Here’s something most explanations skip. The formula also produces primes for negative values of n, from -40 to -1. If you plug in n = -1, you get (-1)² + (-1) + 41 = 1 – 1 + 41 = 41. Prime.

Try n = -2: 4 – 2 + 41 = 43. Prime. This continues all the way to n = -40, which gives 1600 – 40 + 41 = 1601. Still prime. So the formula actually produces primes for 80 consecutive integers: from -40 to 39. (The values at the extremes, n = -40 and n = 39, both give 1601.)

The Connection to Heegner Numbers

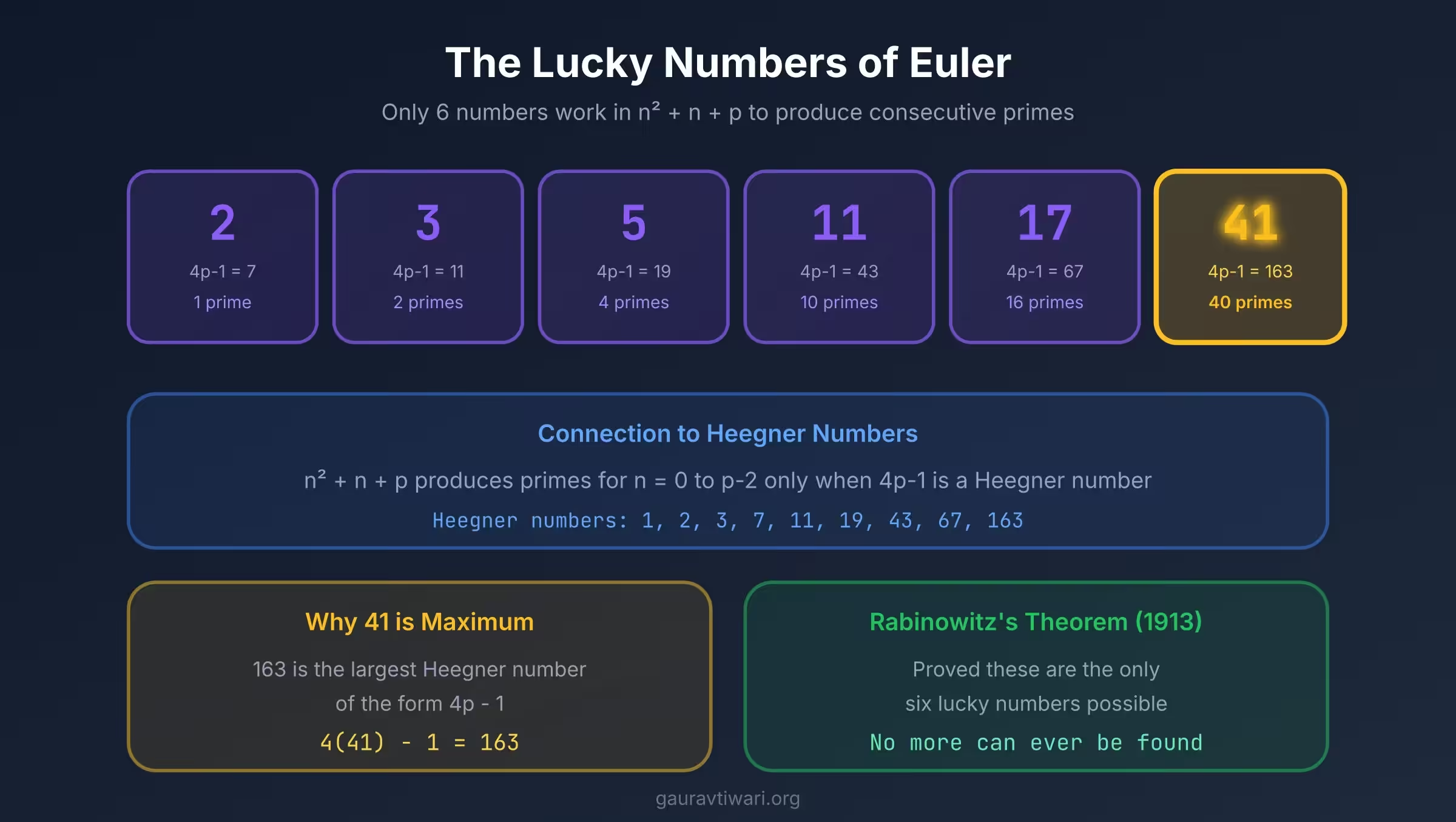

The number 41 isn’t random. It connects to one of the deepest results in number theory. There’s a concept called Heegner numbers, which are specific integers with a remarkable property in algebraic number theory. The complete list is: 1, 2, 3, 7, 11, 19, 43, 67, and 163.

Notice that 163 is on this list. And 163 = 4 × 41 – 1. This relationship isn’t an accident. The mathematical structures that make Heegner numbers special are the same structures that make Euler’s formula produce so many primes.

Rabinowitz proved in 1913 that n² + n + p produces primes for n = 0 to p – 2 if and only if 4p – 1 is a Heegner number. Since 4 × 41 – 1 = 163 is indeed a Heegner number, the formula works for those 40 consecutive values.

The Lucky Numbers of Euler

Mathematicians call certain constants “lucky numbers of Euler.” These are positive integers p where n² + n + p is prime for all n from 0 to p – 2. Based on Rabinowitz’s theorem, there are exactly six lucky numbers: 2, 3, 5, 11, 17, and 41.

Each of these corresponds to a Heegner number:

- p = 2 → 4(2) – 1 = 7 (Heegner number)

- p = 3 → 4(3) – 1 = 11 (Heegner number)

- p = 5 → 4(5) – 1 = 19 (Heegner number)

- p = 11 → 4(11) – 1 = 43 (Heegner number)

- p = 17 → 4(17) – 1 = 67 (Heegner number)

- p = 41 → 4(41) – 1 = 163 (Heegner number)

Since there are exactly nine Heegner numbers and only six of them fit the form 4p – 1 for positive integers p, there can never be another lucky number of Euler. The number 41 gives the longest possible run of primes from this type of formula.

A Related Formula With an Even Longer Run

There’s a clever variation: n² – 79n + 1601. This formula produces primes for n = 0 to 79. That’s 80 prime values. But it’s not fundamentally different from Euler’s original. If you substitute m = n – 40 into Euler’s formula, you get this one.

The primes produced are the same. You’re just indexing them differently. The formula n² + n + 41 for n = -40 to 39 gives exactly the same outputs as n² – 79n + 1601 for n = 0 to 79.

The Ulam Spiral Connection

In 1963, physicist Stanislaw Ulam was sitting in a boring meeting and started writing integers in a spiral pattern. When he circled the primes, he noticed they tended to line up along diagonal lines. This is now called the Ulam spiral.

Some of those diagonal lines correspond to quadratic polynomials like Euler’s formula. The visual clustering of primes along certain diagonals reflects the same mathematical structure that makes n² + n + 41 so effective at generating primes.

If you generate the Ulam spiral and trace the values produced by Euler’s formula, they fall on a prominent diagonal. The formula captures a genuine pattern in how primes distribute themselves among the integers.

Can We Find a Formula for All Primes?

No simple formula can produce all primes and only primes. This has been proven. Any polynomial that produces infinitely many values will eventually produce composite numbers. Euler’s formula is remarkable precisely because 40 consecutive primes is so much longer than we’d expect.

There are more complex formulas that technically produce all primes, but they’re useless for practical calculation. They involve operations that essentially encode the primality test into the formula itself. They’re mathematical curiosities, not computational tools.

What makes n² + n + 41 special is its simplicity. A quadratic polynomial with small coefficients producing 40 primes in a row. The connection to deep algebraic structures like Heegner numbers suggests this formula reveals something fundamental about the distribution of primes.

Practical Applications

Prime numbers power modern cryptography. Every secure connection you make online relies on the difficulty of factoring large primes. While Euler’s formula isn’t used directly in cryptography (the primes it generates are too small), understanding prime distribution helps mathematicians develop better algorithms.

The formula also makes an excellent teaching tool. It demonstrates that primes aren’t randomly scattered among integers. There’s structure there, even if we can’t fully characterize it. Showing students that 40 consecutive outputs of a simple quadratic are all prime is a powerful way to spark interest in number theory.

Verification

You don’t have to take anyone’s word for this. Grab a calculator or write a quick program. The formula is simple enough that you can verify every claim yourself.

def is_prime(n):

if n < 2:

return False

for i in range(2, int(n**0.5) + 1):

if n % i == 0:

return False

return True

def euler_formula(n):

return n*n + n + 41

# Check n = 0 to 45

for n in range(46):

result = euler_formula(n)

prime = is_prime(result)

print(f"n={n}: {result} {'Prime' if prime else 'Composite'}")Run this and watch the pattern yourself. Primes from n = 0 through n = 39. Then 1681 = 41² at n = 40.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Euler’s prime generating formula?

Euler’s prime generating formula is n² + n + 41. When you plug in integers from 0 to 39, every result is a prime number. Euler discovered this formula in 1772, and it remains one of the most famous examples of a polynomial that generates an unusually long sequence of consecutive primes.

Why does Euler’s formula fail at n = 40?

At n = 40, the formula produces 40² + 40 + 41 = 1681 = 41². The number 41 in the formula guarantees divisibility when n = 40 because 40(41) + 41 = 41(41). The same constant that makes the formula work for 40 values eventually causes it to fail.

What are Heegner numbers and how do they relate to this formula?

Heegner numbers are special integers in algebraic number theory: 1, 2, 3, 7, 11, 19, 43, 67, and 163. The formula n² + n + p produces primes for n = 0 to p-2 only when 4p – 1 is a Heegner number. Since 4(41) – 1 = 163 is a Heegner number, Euler’s formula works for 40 consecutive values.

Are there other numbers like 41 that work in this formula?

Yes, but only five others. The lucky numbers of Euler are 2, 3, 5, 11, 17, and 41. Each produces primes for n = 0 to p-2. Since there are exactly nine Heegner numbers and only six work in the formula 4p – 1, there can never be another lucky number. The number 41 gives the longest run.

Can any formula generate all prime numbers?

No simple polynomial can produce all primes and only primes. This has been mathematically proven. Any polynomial generating infinitely many values will eventually produce composite numbers. More complex formulas exist that technically work, but they encode primality testing into the formula itself and aren’t useful for calculation.

What is the Ulam spiral and how does it connect to Euler’s formula?

The Ulam spiral is a visualization where integers are written in a spiral pattern and primes are marked. Primes cluster along certain diagonal lines, and some of these diagonals correspond to quadratic polynomials like n² + n + 41. Euler’s formula values fall on a prominent diagonal, showing a genuine pattern in prime distribution.

Euler’s formula captures something beautiful about mathematics. A simple expression connecting quadratic polynomials, prime numbers, and deep algebraic structures. The fact that we can trace why it works, through Rabinowitz’s theorem and Heegner numbers, makes it even more satisfying. It’s not magic. It’s structure.