Create a Business Budget in 2026 That Makes Sense

So, you’ve been running your business for a while now. And you probably have a sense of where money goes. Rent, software, maybe some marketing. But if I asked you right now: “What did you spend on tools last quarter?” or “How much should you budget for client acquisition next month?”, could you answer with actual numbers?

Most small business budgets fail before they even start. They’re either too complex to maintain or too simple to be useful. Like, you’ve got this elaborate spreadsheet with 47 expense categories that you touched exactly twice. Or you’ve got the vague “spend less” intention that provides zero guidance when you’re staring at an expense decision. The freelancer or small business owner ends up flying blind, hoping things work out.

But here’s the thing. A useful business budget isn’t complicated. It answers a few key questions: How much money do I need? Where should money go? Am I on track? A budget that provides these answers in a format you’ll actually use beats a sophisticated model that collects dust. And I’ve spent 16 years figuring out what actually works versus what sounds good in theory.

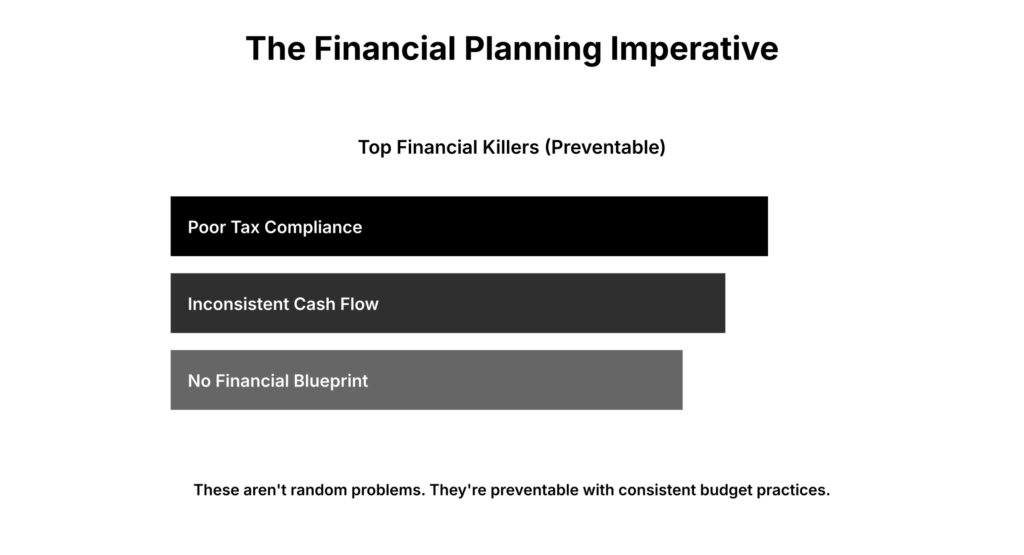

The 2026 Financial Planning Imperative

You remember when poor tax compliance and inconsistent cash flow were just “normal” business challenges? They’re not. They rank among the top 10 financial killers for small businesses. And here’s what nobody tells you: these aren’t random problems that happen to you. They’re preventable with consistent budget practices.

The businesses that struggle financially often lack a blueprint. They react to money problems rather than preventing them. And I’ve watched this play out dozens of times. Client calls me, business is six months behind on bookkeeping, surprise tax bill arrives, panic sets in. Could’ve been avoided entirely.

The ability to accurately track spending is crucial for any well-run business. Knowing where money goes, and which budgets to allocate resources to, gives you full control over your resources. Clear business expense categories make this possible. Without them? Money disappears into undefined “general expenses” that provide no insight. You just can’t find the leak when everything’s pooled together.

Your budget should be treated as a living document. Financial conditions change. Market shifts. Unanticipated opportunities show up. Schedule regular check-ins—monthly or quarterly—to compare actual performance with your budget and make informed adjustments.

Why This Actually Matters

Let me break down the real case for financial planning.

- Clarity. You know where money goes and should go. No more wondering where it all went. Like, you can actually answer “What did I spend last month?” without digging through bank statements.

- Control. Intentional allocation rather than reactive spending. Money goes where it creates value, not where it’s easiest to spend.

- Decision support. Data for business decisions. Can I afford this hire? This tool? This marketing spend? You just know. No guessing.

- Goal progress. Tracking movement toward financial objectives. Savings, debt reduction, investment. You can see the progress. Or lack of progress. Both are useful.

- Stress reduction. And don’t get me wrong, budgets don’t eliminate financial stress. But financial anxiety comes from uncertainty. Budgets create clarity. Clarity reduces stress.

- Cash flow management. Understanding timing of income and expenses. Preventing cash crunches before they arrive.

- Tax preparation. Organized expenses simplify tax time. You know exactly what deductions you’re taking.

A budget is simply a plan for money. Without a plan? Money goes wherever it goes—often to places that don’t serve your business goals.

Core Concepts Before Building

So, now what? Let me explain the fundamentals.

- Income reality. Budget based on actual income, not hoped-for income. I’ve seen freelancers budget for $10,000 months when they’ve never cleared $6,000. That’s not planning. That’s wishful thinking.

- Fixed vs. variable. Fixed costs remain constant—rent, subscriptions. Variable costs fluctuate—materials, marketing. Different planning for each. And the thing is, most people underestimate their variable costs because they only remember the big months.

- Essential vs. discretionary. Essential expenses keep the business running. Discretionary expenses are choices. Know the difference. That new design tool might feel essential. It’s probably discretionary.

- Profit first. Set aside profit before spending, not hoping for leftovers. Because guess what? There are never leftovers.

- Emergency reserves. Buffer for unexpected expenses. Part of budget, not afterthought. The businesses that survive setbacks are the ones who planned for setbacks.

- Personal and business separation. Especially for freelancers. Clear line between business and personal finances. This isn’t about taxes. It’s about knowing whether your business is actually profitable. I spent three years thinking my freelance income was good. Then I tracked expenses properly and realized I’d been subsidizing my business with savings. That was a rough spreadsheet to look at.

- Taxes as expenses. Set aside taxes consistently. Not a surprise in April. Nothing ruins a good revenue month like realizing you owe $15,000 you don’t have.

These fundamentals apply regardless of business size or type. Master them before adding complexity.

Building Your Actual Budget

Step-by-step. This is what actually works.

- Step 1: Know your numbers. Review past 3-12 months of income and expenses. Actual data, not guesses. What did you actually earn? What did you actually spend? And I mean actually. Not “around $3,000”- the real number.

- Step 2: Calculate your baseline income. What’s a realistic monthly income projection? For variable income, use conservative estimates or averages. You remember that $15,000 month last year? Probably shouldn’t base your budget on that if it only happened once.

- Step 3: List fixed expenses. Everything that remains constant: rent, subscriptions, insurance, loan payments. Total these. This is your floor. You can’t go below this without cutting services.

- Step 4: Estimate variable expenses. Categories that fluctuate: marketing, materials, travel, contractors. Use historical averages or reasonable projections. Not best-case scenarios.

- Step 5: Include owner compensation. Your salary or draw. Not afterthought—planned expense. Pay yourself intentionally.

- Step 6: Set aside taxes. 25-30% of income for most self-employed. Adjust based on your situation. I’ve used 30% for years. Better to overset aside than scramble.

- Step 7: Plan profit allocation. What goes to savings, debt reduction, or reinvestment? This is where growth happens.

- Step 8: Create spending categories. Group expenses logically. Not too many categories, not too few. I use about 12. More than that and I stop tracking. Fewer and I lose visibility.

- Step 9: Assign amounts to categories. Based on history and priorities. This is the actual budget. The numbers you’re committing to.

- Step 10: Build in buffer. Contingency for unexpected expenses. 5-10% of total budget. Because things break. Clients delay payment. Surprises happen.

Start simple. Refine over time as you learn what categories and detail levels work for you.

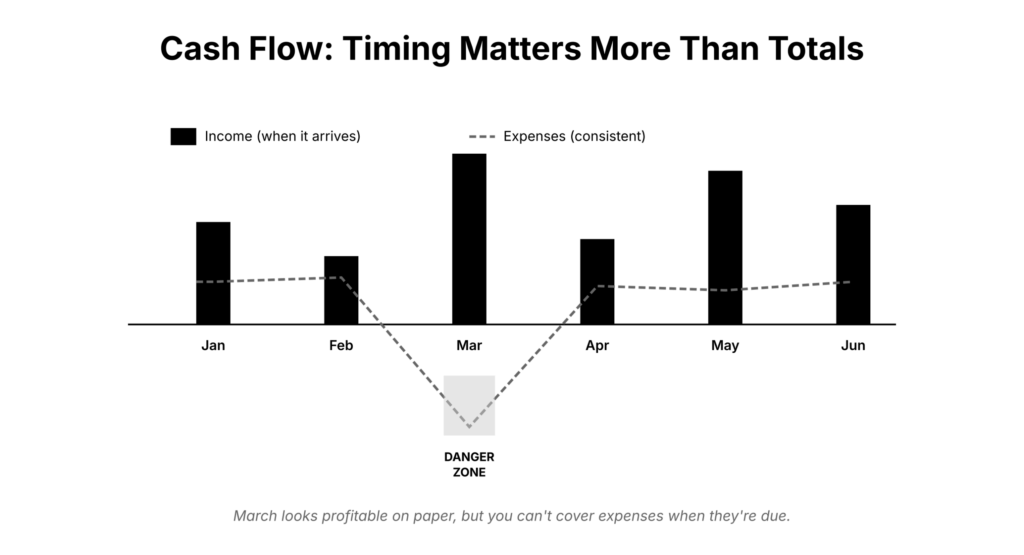

Cash Flow: The Timing Problem

Here’s what kills profitable businesses. You might earn $100,000 this year. Great number. But that doesn’t help if you need $20,000 in March and most income arrives in November. Cash flow forecasting projects when money comes in and when it goes out. The gap between those two? That’s what matters.

- Map payment timing. When do clients actually pay? Because invoicing doesn’t equal cash. I’ve had clients take 90 days to pay. Some pay in 15. Know your patterns. Track the gap between work completion and payment receipt.

- Identify expense timing. When are major expenses due? Annual insurance, quarterly taxes, monthly rent. Map these across the year to identify months when outflows exceed inflows. Those are your danger zones.

- Calculate runway. How many months of expenses can you cover from current cash? This number should stay above three months, ideally six. Watch runway trends. Declining runway signals trouble before it arrives.

- Build cash cushions. When cash flow is positive, build reserves for when it isn’t. The businesses that struggle often have adequate annual income but inadequate cash management. Like, they made $80,000 last year but closed in February because they couldn’t cover rent.

- Plan major purchases. Time capital expenditures for cash-strong periods. Spreading payments through financing can smooth cash flow if rates are reasonable. But don’t finance because you have no cash. Finance because it makes strategic sense.

Cash flow problems kill businesses with adequate revenue. Budget for timing, not just totals.

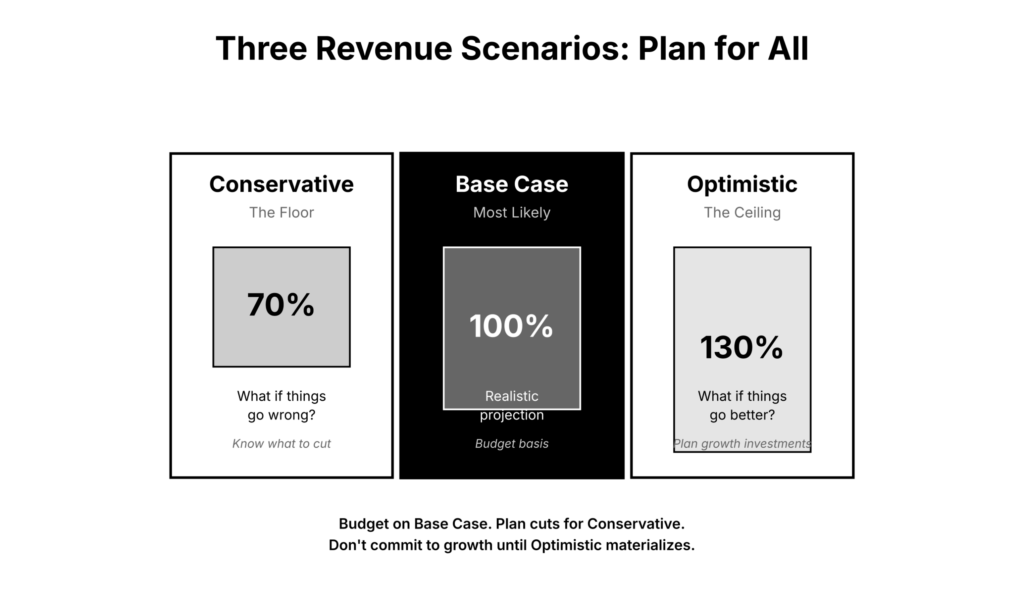

Projecting Revenue Realistically

You need three scenarios.

- Base case projection. What income is reasonably likely? Use historical data and current pipeline. This is your primary budget basis. Most of your decisions should be based on this number.

- Conservative case. What if things go worse than expected? Lose a major client, miss targets, experience market downturn. What’s the floor? I plan for 70% of my base case. Gives me room to handle problems.

- Optimistic case. What if things exceed expectations? Win new clients, prices increase, economy booms. What’s the ceiling? This is where you plan growth investments. But you don’t commit to them until the revenue materializes.

Probability weighting. Base case gets most weight. But having scenarios prepared enables faster response to changing conditions. You’re not scrambling to figure out what to cut when things go sideways.

Lagging indicators. Revenue often lags business activity. Orders placed today become revenue next month. Account for these delays in projections. I typically see a 30-45 day lag between closing a deal and getting paid.

Recurring versus one-time. Recurring revenue is more predictable than project-based income. Weight your confidence accordingly. I’m 90% confident in my recurring revenue projections. Maybe 60% confident in project pipeline.

Pipeline realism. Prospective deals aren’t revenue until they close. Discount pipeline appropriately based on your historical conversion rates. If you close 30% of proposals, that $50,000 pipeline is really $15,000 of expected revenue.

Conservative projections prevent overextension. Optimistic planning when it doesn’t materialize creates cash problems.

Taxes

So let me explain how to actually handle taxes.

- Quarterly estimates. Self-employed individuals pay quarterly estimated taxes. Budget for these and schedule payments to avoid penalties. Set reminders. I use recurring calendar events. Can’t forget when it’s automated.

- Tax rate estimation. 25-30% of income is a reasonable starting estimate for combined federal and state taxes. Adjust based on your actual situation and deductions. I use 30%. Covers me every time.

- Set-aside discipline. Transfer tax portions to a separate account when income arrives. Money you can see is money you might spend. I have a dedicated tax savings account. Money goes in, doesn’t come out until tax time.

- Deduction tracking. Document business expenses throughout the year. Categories in your budget often align with tax categories. Makes filing so much easier when everything’s already organized.

- Professional advice. Tax strategy affects budgeting. A consultation with a tax professional can save more than it costs. I meet with my accountant quarterly. Costs $500 per session. Saves me thousands in optimized deductions.

- Year-end planning. December decisions affect tax liability. Timing of expenses and income matters. Plan rather than react. You can shift income or accelerate expenses strategically if you know your situation.

Categories That Actually Work

Here’s how I organize expenses. Customize for your business, but this is the starting point.

- Core operations. Rent, utilities, essential subscriptions—the business wouldn’t function without these. This is typically 20-30% of my budget.

- Tools and technology. Software, hardware, services that enable work. Understanding if marketing is working.

- Marketing. Advertising, content creation, promotional activities. The thing is, most businesses either spend nothing or overspend. Find the middle ground.

- Professional services. Accounting, legal, consulting. Expert help when needed. Worth every penny when you actually need it.

- Education and development. Training, courses, books. Skill investment. I budget 5% of revenue here. Compounds over time.

- Team and contractors. Anyone you pay to help with work. Biggest variable expense for most service businesses.

- Travel and meetings. Business travel, client entertainment. Went way down after [year-2]. Remote work changed everything.

- Office and supplies. Physical materials, workspace costs.

- Insurance. Business insurance and health coverage. Non-negotiable.

- Taxes. Set-asides for quarterly and annual taxes.

- Savings and reserves. Emergency fund contributions, planned savings.

- Owner compensation. Your pay from the business.

Tracking: The Part Nobody Wants to Do

A budget only works if you track against it. And I get it. Tracking feels tedious. But either way, you need to know where you stand.

- Regular review. Weekly or monthly comparison of actual versus budgeted. I do this every Monday morning. Takes 15 minutes.

- Variance analysis. When actual differs from budget, understand why. Legitimate reason or spending problem? Both happen. But you need to know which is which.

- Category monitoring. Which categories consistently over or under budget? Adjust future budgets accordingly. I’ve learned that I always underbud get marketing. Now I just allocate more upfront.

- Running totals. Year-to-date tracking against annual budget. Are you on pace? This is the number that actually matters.

- Course correction. When off track, adjust either spending or budget. Don’t ignore variances. They compound.

- Simple tools. Spreadsheet, accounting software, or dedicated budgeting apps. Whatever you’ll actually use. I’ve tried fancy tools. A Google Sheet works best for me.

Tracking takes just minutes per week. The insight it provides is well worth the time invested.

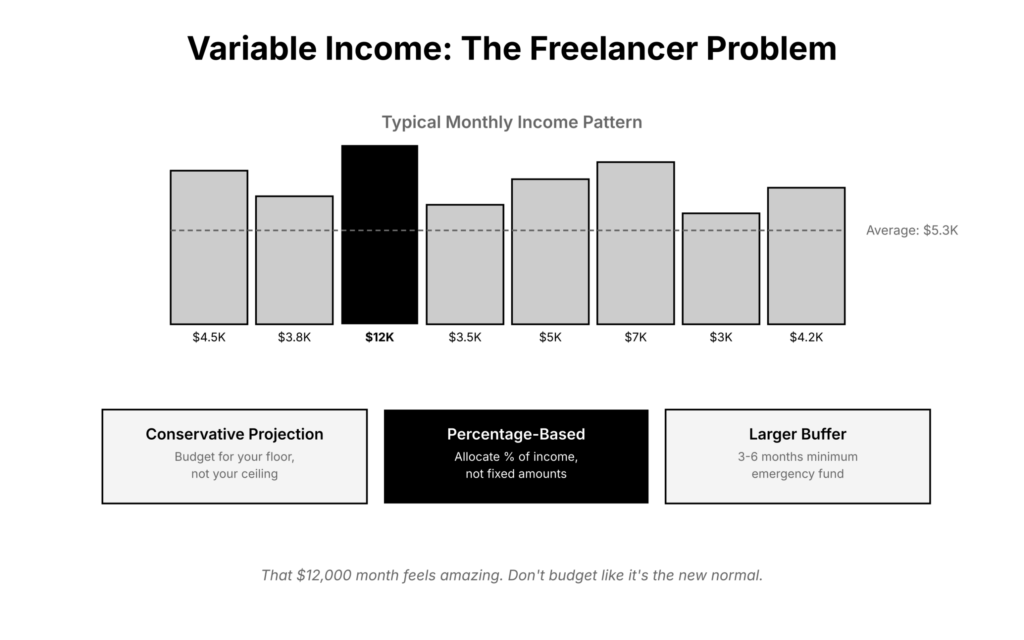

Variable Income: The Freelancer Problem

So, freelancers and project-based businesses face unique challenges. Let me show you what actually works.

- Conservative income projection. Budget for your floor, not your ceiling. Windfalls go to savings, not spending. This is the hardest rule to follow. That $12,000 month feels amazing. Don’t budget like it’s the new normal.

- Percentage-based budgeting. Allocate percentages of income rather than fixed amounts. Scales with revenue. When income is high, everything scales up. When income drops, everything scales down automatically.

- Monthly average smoothing. Annual income divided by 12 for monthly planning, even if actual income varies. Psychologically easier to manage.

- Expense prioritization. When income is low, know what to cut first. Essential versus discretionary clarity. I have a three-tier system: never cut, cut if needed, cut immediately. Decided in advance, not during crisis.

- Buffer emphasis. Larger emergency fund for income volatility. Three to six months expenses minimum. I keep six. Variable income requires more cushion.

- Income goals. Monthly and annual revenue targets that inform budget assumptions. But goals aren’t projections. Don’t confuse the two.

- Scenario planning. What if income drops 30%? What expenses would you cut? Plan before you need to. I’ve run this scenario a dozen times. Know exactly what I’d do.

Variable income requires more conservative budgeting, not less budgeting.

Profit First: Reverse Engineering

Traditional approach says: Revenue – Expenses = Profit. Profit is whatever’s left. Which is usually nothing.

Profit First approach says: Revenue – Profit = Expenses. Profit is taken first, expenses fit what remains. And the thing is, this works because it enforces discipline through structure.

Implementation. When money comes in, immediately allocate percentages to separate accounts: profit, taxes, operating expenses, owner pay. I use four checking accounts. Money gets distributed on receipt. Can’t spend what’s not in the operating account.

Forced discipline. Can’t spend what’s already allocated elsewhere. Budget enforced by structure, not willpower.

Percentage guidelines. Vary by revenue level, but typically: profit (5-15%), taxes (15-35%), owner pay (25-50%), operating (15-30%). These percentages shift as revenue grows.

Gradual implementation. Start with small profit percentage and increase over time. I started at 5%. Now at 15%. Took three years to get there.

Profit First provides structure that prevents overspending, especially for those who struggle with traditional budgets. It’s not for everyone. But if you consistently end months with zero profit despite decent revenue? Try this.

Planning for Growth

Growth requires intentional investment. Budget for it explicitly rather than hoping for extra money. Because there’s never extra money unless you allocate for it.

- Investment categories. Separate budgets for growth spending versus maintenance spending. Know the difference. Growth spending should have expected returns. Maintenance spending keeps things running.

- Hiring budgets. When to hire, what to pay, total cost including taxes and benefits. Plan before committing. I’ve made this mistake. Hired without proper budgeting. Stressful. Don’t recommend.

- Marketing investment. Allocating funds for customer acquisition. Understanding acceptable acquisition costs. If a client is worth $5,000 lifetime value, spending $1,000 to acquire them makes sense. Spending $6,000 doesn’t.

- Tool and infrastructure. Systems that enable scale. Planning major purchases. Sometimes spending $500/month on automation saves $2,000/month in time. Do the math first.

- Revenue targets. Growth budget tied to revenue goals. Investment justified by expected returns. This isn’t a leap of faith. It’s calculated investment.

- Conservative staging. Increase growth spending as revenue proves out. Don’t bet the business on projections. Test small, scale what works.

- Runway awareness. How long can you sustain growth investment without returns? Know your limits. I won’t invest in growth if it drops runway below four months.

Strategic Expense Reduction

When budget needs reduction. And sometimes it does.

- Audit all expenses. Review every line item. What’s actually necessary? I do this annually. Always find subscriptions I forgot I had.

- Subscription review. Tools and services often accumulate. Cancel what’s not actively used. That $29/month tool you haven’t opened in three months? Gone.

- Renegotiation. Vendors often have flexibility. Ask for better rates. You’d be surprised how often this works. I’ve negotiated better hosting rates just by asking.

- Discretionary first. Cut nice-to-have before essential. Know the difference. And don’t get me wrong, sometimes “nice-to-have” is actually driving revenue. Protect those.

- Efficiency gains. Sometimes spending more on one thing reduces total spending. Automation, better tools. I spent $2,000 on automation that saved me 10 hours per week. ROI was immediate.

- Revenue focus. Sometimes increasing revenue is easier than cutting expenses. Both matter. But cutting to zero still leaves you at zero. Growing revenue has upside.

- Avoid false economy. Cutting expenses that generate revenue is counterproductive. Cut strategically, not desperately.

Mistakes That Kill Budgets

What undermines business budgeting. I’ve made most of these mistakes. Learn from them.

- Overcomplication. Too many categories, too much detail. Unsustainable to maintain. The 47-category budget I mentioned earlier? That was me. Used it twice.

- Undercomplication. No useful detail. “Spend less” isn’t a budget. Neither is three categories: “stuff,” “things,” “other.”

- Unrealistic revenue. Budgeting for income you hope to earn. Creates spending problems. This is the fastest way to overspend.

- Ignoring taxes. Treating tax obligations as optional. They’re not. They’re the most mandatory expense you have.

- No profit allocation. Profit as afterthought. Never arrives. Profit First fixes this entirely.

- Personal/business mixing. Unclear what’s business expense. Tracking becomes impossible. Taxes become painful. Just don’t.

- Set and forget. Creating budget then never reviewing. Budgets require ongoing attention. Like maybe 30 minutes per week.

- Guilt without action. Seeing variances, feeling bad, doing nothing. Action matters. Guilt doesn’t.

- Perfect over useful. Waiting for perfect budget instead of starting with good enough. Start now. Refine later.

Review and Evolution

Budgets evolve. They should.

- Monthly review. Compare actual to budget. Note variances. Understand causes. This is non-negotiable. You need to know where you stand.

- Quarterly adjustment. Revise budget based on actual patterns. Reality informs future planning. Every quarter I adjust something based on what I learned.

- Annual planning. Major budget revision annually. Incorporate lessons from previous year. New revenue targets, new expense patterns, new priorities.

- Trigger-based review. Major business changes trigger budget review: new clients, lost clients, major expenses. Don’t wait for scheduled review when circumstances change dramatically.

- Category refinement. Add or remove categories as you learn what tracking is useful. My categories have evolved significantly over 16 years.

- Process improvement. How you budget and track can improve over time. Find what works for you. I’ve tried a dozen systems. Current one is simple and sustainable.

Tools That Actually Help

From simple to sophisticated.

- Accounting software. FreshBooks or QuickBooks integrates accounting and budgeting in one platform. These tools provide cash flow management for tracking the timing of income and expenses, budget versus actual comparison with side-by-side projected versus actual numbers, and growth planning sections for capital expenditures. I’ve used FreshBooks for eight years. Does everything I need.

- Spreadsheets. Google Sheets or Excel. Maximum flexibility, requires more manual work. Started here. Still use spreadsheets for certain projections.

- Project management. ClickUp or monday.com helps track project-based expenses and resource allocation.

- Time tracking. Toggl connects time spent to project profitability, essential for service businesses. Can’t improve what you don’t measure.

- Dedicated budgeting apps. YNAB, Monarch. Budget-focused with automation. Great for some people. Too restrictive for me.

- Bank account structure. Multiple accounts for different purposes (Profit First approach). This is free. Just open more accounts.

- Accounting professionals. Bookkeepers and accountants who can set up and maintain systems. Worth the investment if numbers aren’t your thing.

Start simple. Add complexity only when simple doesn’t meet your needs.

The Reality Check

Once your budget is set, the next step is getting visibility without overspending. My SEO services help small businesses grow organically instead of burning cash on ads. For tracking what’s working, the marketing ROI calculator puts actual numbers behind your marketing spend. If you’re a service business, the freelance rate calculator helps price your work profitably.

So here’s what actually matters. The budget that works is the one you use. A perfect budget abandoned is worse than a simple budget followed. I’ve seen both. The simple budget wins every time.

Start with something manageable. Track consistently. Refine over time. Financial clarity is achievable without financial complexity. You don’t need 47 expense categories and three-way variance analysis. You need to know where money goes, where it should go, and whether you’re on track.

And the thing is, most business financial problems aren’t complex. They’re basic: spending more than earned, not planning for taxes, confusing revenue with profit, ignoring cash flow timing. A basic budget prevents all of these. Not through sophisticated analysis. Through consistent attention.

You just can’t manage what you don’t measure. And you can’t improve what you don’t manage. The budget is the starting point. Everything else builds from there.

Disclaimer: This site is reader-supported. If you buy through some links, I may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. I only recommend tools I trust and would use myself. Your support helps keep gauravtiwari.org free and focused on real-world advice. Thanks. - Gaurav Tiwari