Bhaskara II’s Lilavati: Complete Reference Guide (Download PDF)

I first encountered the Lilavati as a student in India, and it completely changed how I thought about mathematics education. Here’s a 12th-century textbook that wraps arithmetic, algebra, and geometry inside riddles about bees, snakes, peacocks, and beautiful maidens. Bhaskara II (also known as Bhaskaracharya, 1114-1185 CE) didn’t write a dry reference manual. He wrote poetry that teaches you math. And it’s been studied for over 850 years. The Lilavati book, written by Bhaskaracharya, remains one of the most influential mathematical texts in history, studied across Asia and eventually Europe.

What makes the Lilavati remarkable isn’t just the math itself, though the math is extraordinary. It’s the pedagogical approach. While other mathematicians of the era wrote dense technical manuals, Bhaskara embedded his mathematics in vivid word problems that made abstract concepts tangible and memorable. A calculation about ratios became a puzzle about monkeys playing in a garden. A geometry problem transformed into a peacock hunting a snake. From zero and negative numbers to iterative algorithms and the Chakravala method, the Lilavati contains ideas that anticipated European mathematics by centuries.

This guide covers everything you need to know about Lilavati: the mathematician behind the text, the legend of how it got its name, detailed modern solutions to its most famous problems, the mathematical methods it presents, its lasting influence on world mathematics, and where to find the Lilavati book PDF in English and Sanskrit. I’ve included complete worked solutions so you can follow along with pen and paper.

Bhaskaracharya: The Mathematician Behind Lilavati

Biographical Overview

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Bhaskaracharya (Bhaskara II) |

| Born | 1114 CE; Vijjalavida, Karnataka, India |

| Died | c. 1185 CE; Ujjain, Madhya Pradesh, India |

| Father | Mahesvara (mathematician and astronomer) |

| Position | Head of Astronomical Observatory, Ujjain |

| Known for | Siddhanta Shiromani, Lilavati, Bijaganita; Chakravala method, early concepts of calculus |

Bhaskaracharya was born in 1114 CE in Vijjalavida (in the modern-day Bijapur district of Karnataka, India). His father, Mahesvara, was also a mathematician and astronomer, which meant Bhaskara grew up surrounded by mathematical manuscripts and astronomical instruments. This intellectual environment shaped his extraordinary career.

By the age of 36, Bhaskara II had completed his magnum opus: the Siddhanta Shiromani (“Crown of Treatises”). This was not a single book but four interconnected volumes covering different branches of mathematics and astronomy. The Lilavati mathematician biography typically focuses on his work in calculus, where he discovered differential calculus concepts centuries before Newton and Leibniz formalized them in Europe.

Bhaskara II served as the head of the astronomical observatory at Ujjain – the same prestigious position once held by the legendary mathematician Brahmagupta – until his death around 1185 CE. His works were translated into Persian, Arabic, and eventually European languages, influencing mathematical development across cultures.

Remark. Bhaskara II should not be confused with Bhaskara I (c. 600-680 CE), an earlier Indian mathematician who also made significant contributions to mathematics and astronomy. The numeral “II” is used by modern historians to distinguish the two.

Mathematical Achievements

What set Bhaskara apart from his contemporaries was not only the depth of his mathematical knowledge but his writing style. While other mathematicians wrote dry technical manuals, Bhaskara embedded his mathematics in vivid word problems. A calculation about ratios became a puzzle about monkeys playing in a garden. A geometry problem transformed into a peacock hunting a snake. His contributions span multiple domains:

- Arithmetic and Algebra: Systematic treatment of operations with zero, negative numbers, surds (irrational numbers), and indeterminate equations.

- Calculus: Discovery of differential calculus concepts – including the derivative and differential coefficient – centuries before Newton and Leibniz formalized them in Europe.

- Astronomy: Accurate calculations of planetary positions, eclipses, and the length of the tropical year.

- Number Theory: The Chakravala method for solving Pell’s equation, not rediscovered in Europe until Lagrange’s work in the 18th century.

The Siddhanta Shiromani

The Siddhanta Shiromani consists of four parts:

Definition (Siddhanta Shiromani). The Siddhanta Shiromani (“Crown of Treatises”) is Bhaskara II’s four-volume magnum opus, comprising:

- Lilavati – Arithmetic, geometry, and combinatorics

- Bijaganita – Algebra, including indeterminate equations

- Grahaganita – Planetary mathematics and astronomy

- Goladhyaya – Spherical astronomy and the celestial sphere

The Lilavati, as the first and most accessible volume, became by far the most widely read and studied. Its influence on mathematics education persisted for over eight centuries across the Indian subcontinent and beyond.

Bhaskaracharya's Lilavati: Ancient Indian Mathematics

- 100% Free Download

- Explore the mathematical genius of 12th-century India through Bhaskaracharya’s Lilavati. Covers arithmetic, geometry, the Kuttaka method, Chakravala algorithm, and famous problems like the Peacock and the Snake. Includes historical context and comparisons with Greek and Chinese mathematics.

The Legend of Lilavati

The name “Lilavati” means “beautiful” or “playful” in Sanskrit. According to a celebrated legend, it was the name of Bhaskara’s daughter.

The Legend: Bhaskara, being an accomplished astronomer, cast his daughter Lilavati’s horoscope and discovered she had a narrow window for an auspicious marriage. He designed a water clock to track the precise moment. As Lilavati watched the device, a pearl from her dress fell into the water and blocked the hole, stopping the clock. The auspicious moment passed unnoticed. Lilavati’s marriage never happened.

To console his daughter, Bhaskara wrote a mathematics treatise in her name, addressing many problems directly to her with affectionate phrases such as “Oh Lilavati, intelligent girl…” and “Tell me, beautiful one…”

Whether this story is historically accurate remains debated among scholars; some think it is a later embellishment. But the affectionate tone throughout the Lilavati granth original text is undeniable. Bhaskara wanted his mathematics to be engaging, personal, and memorable. This personal touch made the book feel less like a textbook and more like a conversation between father and daughter.

Remark. The personal address in mathematical texts was unusual for the era. Most treatises were written in an impersonal, formal style. Bhaskara’s conversational approach was a pedagogical innovation that anticipated modern principles of student engagement by nearly a millennium.

The Structure of Lilavati

The Lilavati contains thirteen chapters, progressing from basic arithmetic to advanced problem-solving techniques. We summarize each chapter below.

Chapter 1: Definitions and Basic Operations

The opening chapter establishes fundamental terms and operations. Bhaskara defines numbers, place values, and the basic operations of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. He also introduces the concept of zero, which Indian mathematicians had developed centuries earlier.

Chapter 2: Fractions

Operations with fractions are covered in detail, including addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and simplification, all presented through practical examples involving trade, measurement, and distribution.

Chapter 3: Zero and Negative Numbers

Bhaskara on Zero: Bhaskara explores the properties of zero, including division by zero. He correctly identifies that \( \dfrac{a}{0} \) leads to infinity (which he calls khahara), writing:

“A quantity divided by zero becomes a fraction the denominator of which is zero. This fraction is termed an infinite quantity.”

While not fully rigorous by modern standards, this showed remarkable insight into the concept of limits.

Bhaskara also addresses operations with negative numbers, treating negative quantities as natural mathematical objects with consistent operational rules – something European mathematicians struggled to accept well into the 18th century.

Chapter 4: Square and Cube Roots

Bhaskara presents efficient algorithms for calculating square roots and cube roots of integers and fractions. His iterative methods remained standard practice in Indian mathematics education for centuries.

Theorem (Bhaskara’s Square Root Algorithm). To find \( \sqrt{N} \), choose an initial approximation \( a \) such that \( a^2 \approx N \). Then refine using:

$$ \sqrt{N} \approx a + \frac{N – a^2}{2a} $$

This is equivalent to one step of Newton’s method applied to \( f(x) = x^2 – N \).

Chapter 5: Arithmetic Progressions

This section covers sequences where each term increases by a constant difference. Bhaskara provides the formula for the sum of an arithmetic series:

Sum of an Arithmetic Progression:

$$ S_n = \frac{n}{2}\bigl(2a + (n-1)d\bigr) $$

where \( n \) is the number of terms, \( a \) is the first term, and \( d \) is the common difference.

Chapter 6: Geometric Progressions

Bhaskara extends to sequences where each term is multiplied by a constant ratio:

$$ S_n = a \cdot \frac{r^n – 1}{r – 1} $$

where \( r \) is the common ratio. This formula, known in India well before Bhaskara’s time, was presented by him with particularly clear examples.

Chapter 7: Plane Geometry

This substantial chapter covers properties of triangles, quadrilaterals, and circles. Bhaskara presents formulas for areas, perimeters, and relationships between geometric figures.

Theorem (Area of a Triangle – Heron’s Formula). For a triangle with sides \( a \), \( b \), and \( c \), the area is:

$$ A = \sqrt{s(s-a)(s-b)(s-c)} $$

where \( s = \dfrac{a+b+c}{2} \) is the semi-perimeter.

Remark. This formula was known in India before Heron of Alexandria (c. 10-70 CE). Indian mathematicians attribute it to earlier traditions. Bhaskara’s contribution was a particularly elegant proof and systematic presentation.

Chapter 8: Solid Geometry

Volumes and surface areas of three-dimensional shapes including spheres, cones, and pyramids. Bhaskara uses the approximations \( \pi \approx \frac{22}{7} \) (for rough calculations) and the more accurate \( \pi \approx \frac{355}{113} \).

Chapter 9: The Shadow of the Gnomon

This chapter applies geometry to astronomical measurements using shadow calculations. A gnomon is a vertical stick whose shadow length changes with the sun’s position.

Example. If a gnomon of height \( h \) casts a shadow of length \( s \), then the altitude angle \( \alpha \) of the sun satisfies:

$$ \tan \alpha = \frac{h}{s} $$

Bhaskara shows how to calculate solar angles, time, and geographical latitude from shadow measurements.

Chapter 10: The Pulverizer (Kuttaka)

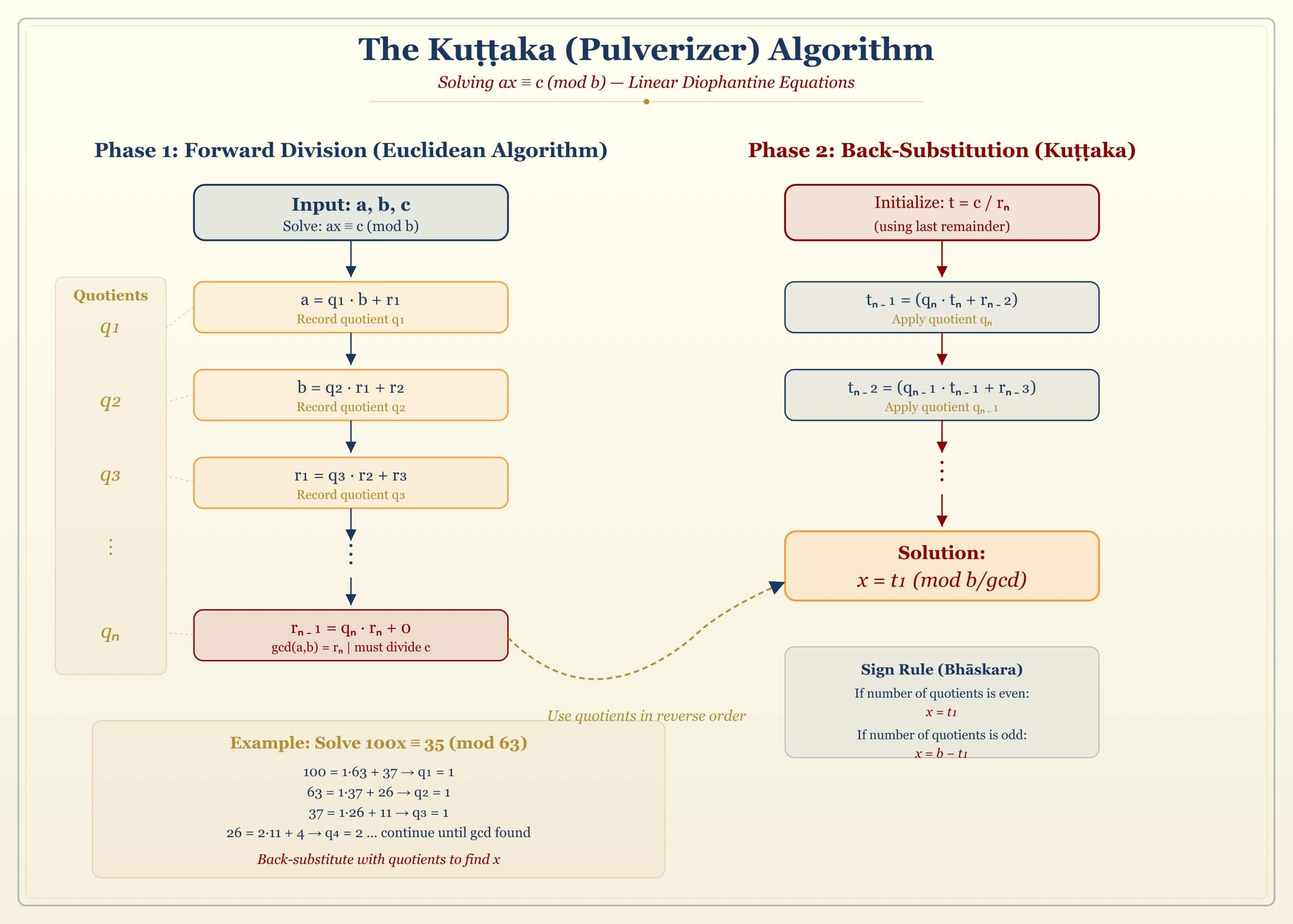

Definition (Kuttaka). The Kuttaka (“pulverizer”) is a method for solving linear indeterminate equations of the form:

$$ ax + by = c $$

where integer solutions \( (x, y) \) are sought. The method proceeds by a sequence of divisions analogous to the Euclidean algorithm.

This technique, refined over centuries by Indian mathematicians from Aryabhata onwards, produces integer solutions when they exist. Bhaskara’s treatment is among the most complete and systematic.

Chapter 11: Combinations and Permutations

Bhaskara presents methods for counting arrangements and selections:

Theorem (Combinations). The number of ways to choose \( r \) objects from \( n \) distinct objects is:

$$ \binom{n}{r} = \frac{n!}{r!\,(n-r)!} $$

Bhaskara expresses this through examples involving selections of tastes (sweet, sour, bitter, etc.) and provides a systematic method for enumeration.

Chapter 12: Net of Numbers

This chapter covers magic squares and number patterns with specific properties, demonstrating Bhaskara’s interest in recreational mathematics alongside serious computation.

Chapter 13: Miscellaneous Problems

The final chapter presents diverse word problems combining techniques from earlier chapters. Many of the Lilavati‘s most famous puzzles appear here.

Sample Problems from Lilavati with Detailed Solutions

The best way to appreciate the Lilavati is to work through its problems. We present several classic examples with complete modern solutions, mathematical analysis, and comparisons to modern methods.

Problem 1: The Beautiful Maiden’s Riddle

This is perhaps the Lilavati‘s most famous problem.

Problem (The Beautiful Maiden). “A beautiful maiden, with beaming eyes, asks: which is the number that, multiplied by 3, then increased by three-fourths of the product, divided by 7, diminished by one-third of the quotient, multiplied by itself, diminished by 52, the square root found, the addition of 8, and division by 10 gives the number 2?”

Solution. The solution requires working backwards through each operation, undoing them one at a time.

Step 1: Start with the final result: \( 2 \).

Step 2: Undo “division by 10”: \( 2 \times 10 = 20 \).

Step 3: Undo “addition of 8”: \( 20 – 8 = 12 \).

Step 4: Undo “square root found”: \( 12^2 = 144 \).

Step 5: Undo “diminished by 52”: \( 144 + 52 = 196 \).

Step 6: Undo “multiplied by itself”: \( \sqrt{196} = 14 \).

Now we must undo the chain of operations applied to the unknown number \( n \):

Step 7: The operations on \( n \) are:

$$ \begin{aligned} \text{Multiply by 3:} &\quad 3n \\ \text{Increase by } \tfrac{3}{4} \text{ of the product:} &\quad 3n + \tfrac{3}{4}(3n) = 3n + \tfrac{9n}{4} = \tfrac{21n}{4} \\ \text{Divide by 7:} &\quad \frac{21n}{4 \times 7} = \frac{3n}{4} \\ \text{Diminish by } \tfrac{1}{3} \text{ of the quotient:} &\quad \frac{3n}{4} – \frac{1}{3} \cdot \frac{3n}{4} = \frac{3n}{4} – \frac{n}{4} = \frac{n}{2} \end{aligned} $$

Step 8: Setting \( \dfrac{n}{2} = 14 \):

$$ \boxed{n = 28} $$

Verification: Starting with \( n = 28 \):

- \( 28 \times 3 = 84 \)

- \( 84 + \frac{3}{4}(84) = 84 + 63 = 147 \)

- \( 147 \div 7 = 21 \)

- \( 21 – \frac{1}{3}(21) = 21 – 7 = 14 \)

- \( 14 \times 14 = 196 \)

- \( 196 – 52 = 144 \)

- \( \sqrt{144} = 12 \)

- \( 12 + 8 = 20 \)

- \( 20 \div 10 = 2 \) ✓

Remark (Modern Algebraic Perspective). In modern notation, the problem can be expressed as the equation:

$$ \frac{\sqrt{\left(\frac{n}{2}\right)^2 – 52} + 8}{10} = 2 $$

The “working backwards” method used by Bhaskara is equivalent to solving this equation by algebraic manipulation. This technique is now standard in puzzle-type problems and is taught in middle school under the name “inverse operations.”

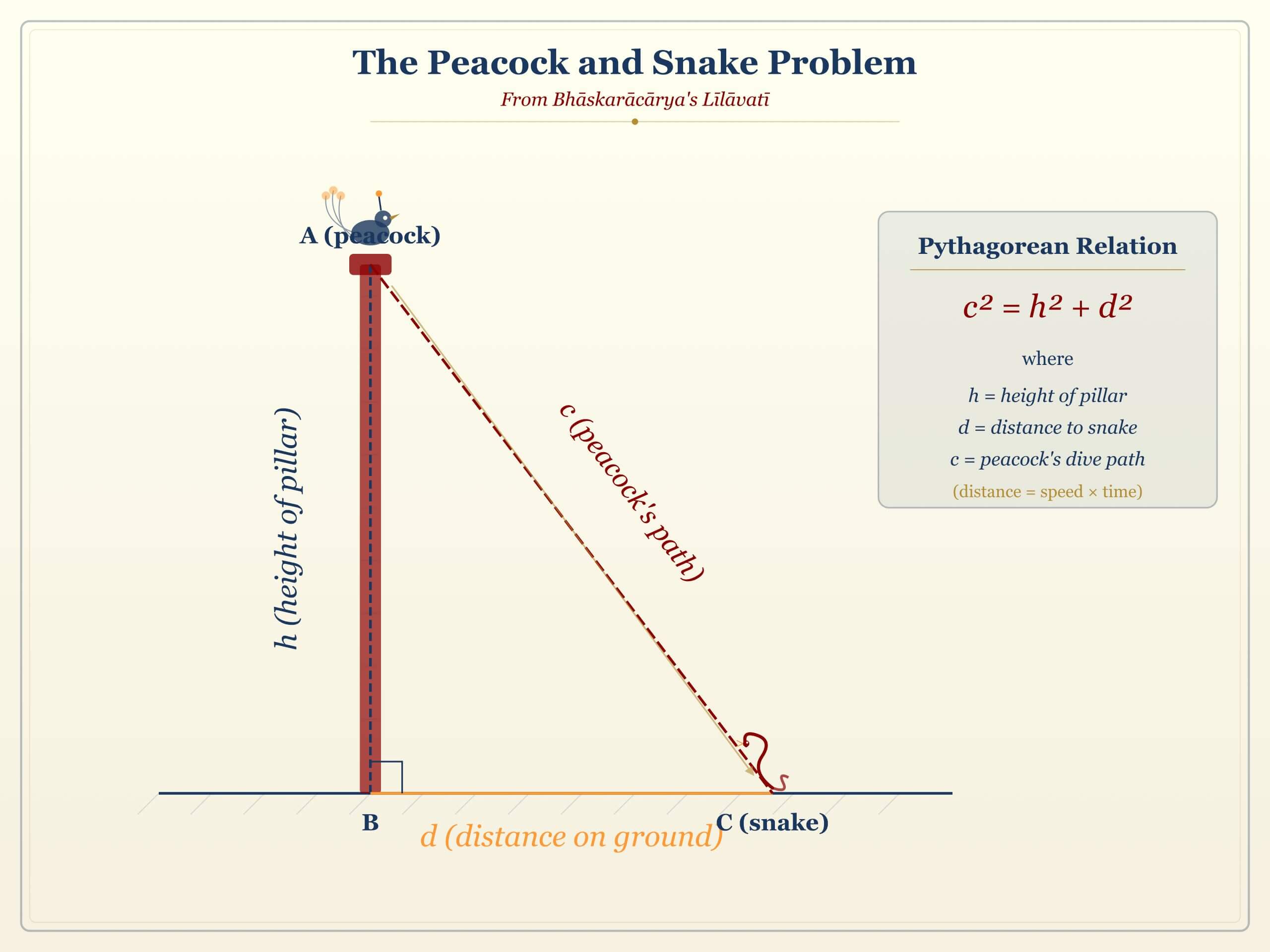

Problem 2: The Peacock and the Snake

Problem (The Peacock and the Snake). “A peacock sits on a pillar 9 feet high. Seeing a snake coming towards its hole at the base of the pillar from a distance of 27 feet, the peacock flies down to catch it. If both move at the same speed, at what distance from the pillar do they meet?”

Solution. Let \( x \) be the distance from the base of the pillar where they meet.

- The snake travels from 27 feet away toward the base, covering a distance of \( (27 – x) \) feet.

- The peacock flies diagonally from the top of the 9-foot pillar to the meeting point on the ground. By the Pythagorean theorem, the peacock covers \( \sqrt{9^2 + x^2} = \sqrt{81 + x^2} \) feet.

Since both travel at the same speed and meet simultaneously:

$$ 27 – x = \sqrt{81 + x^2} $$

Squaring both sides:

$$ (27 – x)^2 = 81 + x^2 $$

$$ 729 – 54x + x^2 = 81 + x^2 $$

The \( x^2 \) terms cancel:

$$ 729 – 54x = 81 $$

$$ 648 = 54x $$

$$ \boxed{x = 12} $$

Verification:

- Snake’s distance: \( 27 – 12 = 15 \) feet.

- Peacock’s distance: \( \sqrt{81 + 144} = \sqrt{225} = 15 \) feet. ✓

Remark (Geometric Interpretation). This problem is a beautiful application of the Pythagorean theorem disguised as a nature story. The key insight is that the \( x^2 \) terms cancel, reducing a potentially difficult quadratic to a simple linear equation. This cancellation occurs because the equal-speed constraint creates a relationship that eliminates the squared unknown.

In modern terminology, the meeting point lies on the perpendicular bisector of the line segment joining the snake’s starting position and the peacock’s starting position (projected onto the ground). This is because all points equidistant from two fixed points lie on their perpendicular bisector.

Example (Generalization). If the pillar has height \( h \) and the snake starts at distance \( d \), the meeting point is at distance \( x \) from the pillar where:

$$ x = \frac{d^2 – h^2}{2d} $$

This formula requires \( d > h \) for a physically meaningful solution (\( x > 0 \)). For \( h = 9 \) and \( d = 27 \): \( x = \frac{729 – 81}{54} = \frac{648}{54} = 12 \).

Problem 3: The Bees and the Lotus

Problem (The Bees and the Lotus). “One-fifth of a swarm of bees flew to the Kadamba flower, one-third flew to the Silandhara, three times the difference of these two numbers flew to an arbor. One bee remained, hovering and attracted on each side by the fragrant Ketaki and the Malati. What is the number of bees?”

Solution. Let \( n \) be the total number of bees.

$$ \begin{aligned} \text{Bees to Kadamba:} &\quad \frac{n}{5} \\ \text{Bees to Silandhara:} &\quad \frac{n}{3} \\ \text{Difference:} &\quad \frac{n}{3} – \frac{n}{5} = \frac{5n – 3n}{15} = \frac{2n}{15} \\ \text{Three times the difference (to arbor):} &\quad 3 \times \frac{2n}{15} = \frac{6n}{15} = \frac{2n}{5} \\ \text{Remaining bee:} &\quad 1 \end{aligned} $$

The sum of all parts equals the total:

$$ \frac{n}{5} + \frac{n}{3} + \frac{2n}{5} + 1 = n $$

Finding a common denominator of 15:

$$ \frac{3n}{15} + \frac{5n}{15} + \frac{6n}{15} + 1 = n $$

$$ \frac{14n}{15} + 1 = n $$

$$ 1 = n – \frac{14n}{15} = \frac{n}{15} $$

$$ \boxed{n = 15} $$

Verification: Kadamba: \( 3 \); Silandhara: \( 5 \); Arbor: \( 6 \); Remaining: \( 1 \). Total: \( 3 + 5 + 6 + 1 = 15 \). ✓

Remark. This type of problem – where an unknown quantity is divided into fractional parts that must sum to the whole – appears across many ancient mathematical traditions. The Rhind Papyrus of ancient Egypt (c. 1650 BCE) contains similar problems. Bhaskara’s innovation was the poetic framing that makes the problem memorable.

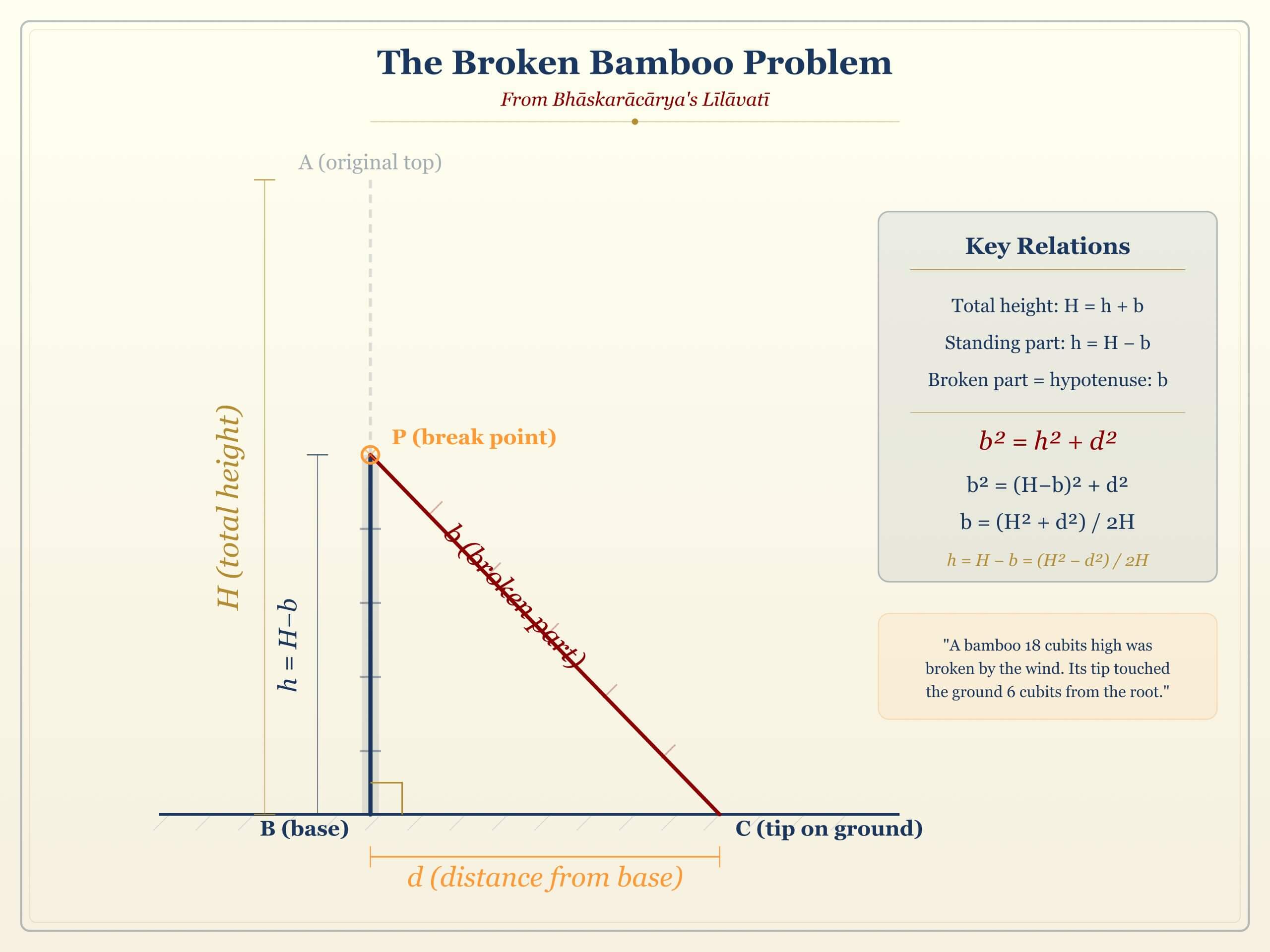

Problem 4: The Broken Bamboo

Problem (The Broken Bamboo). “A bamboo 32 cubits high was broken by the wind. Its tip touched the ground at a distance of 16 cubits from its root. At what height was it broken?”

Solution. Let \( x \) be the height at which the bamboo was broken. Then:

- The standing portion has height \( x \).

- The fallen portion has length \( 32 – x \) (the top part that bent over).

- The fallen portion, the ground, and the standing portion form a right triangle.

By the Pythagorean theorem:

$$ x^2 + 16^2 = (32 – x)^2 $$

$$ x^2 + 256 = 1024 – 64x + x^2 $$

The \( x^2 \) terms cancel:

$$ 256 = 1024 – 64x $$

$$ 64x = 768 $$

$$ \boxed{x = 12} $$

The bamboo was broken at a height of 12 cubits.

Verification: Standing portion: 12. Fallen portion: 20. Check: \( 12^2 + 16^2 = 144 + 256 = 400 = 20^2 \). ✓

Remark. This is another instance where the Pythagorean theorem reduces to a linear equation due to the cancellation of \( x^2 \) terms. Problems of this type appear in Chinese mathematics (Jiuzhang Suanshu, c. 200 BCE) as well, suggesting a possible transmission of mathematical ideas along ancient trade routes.

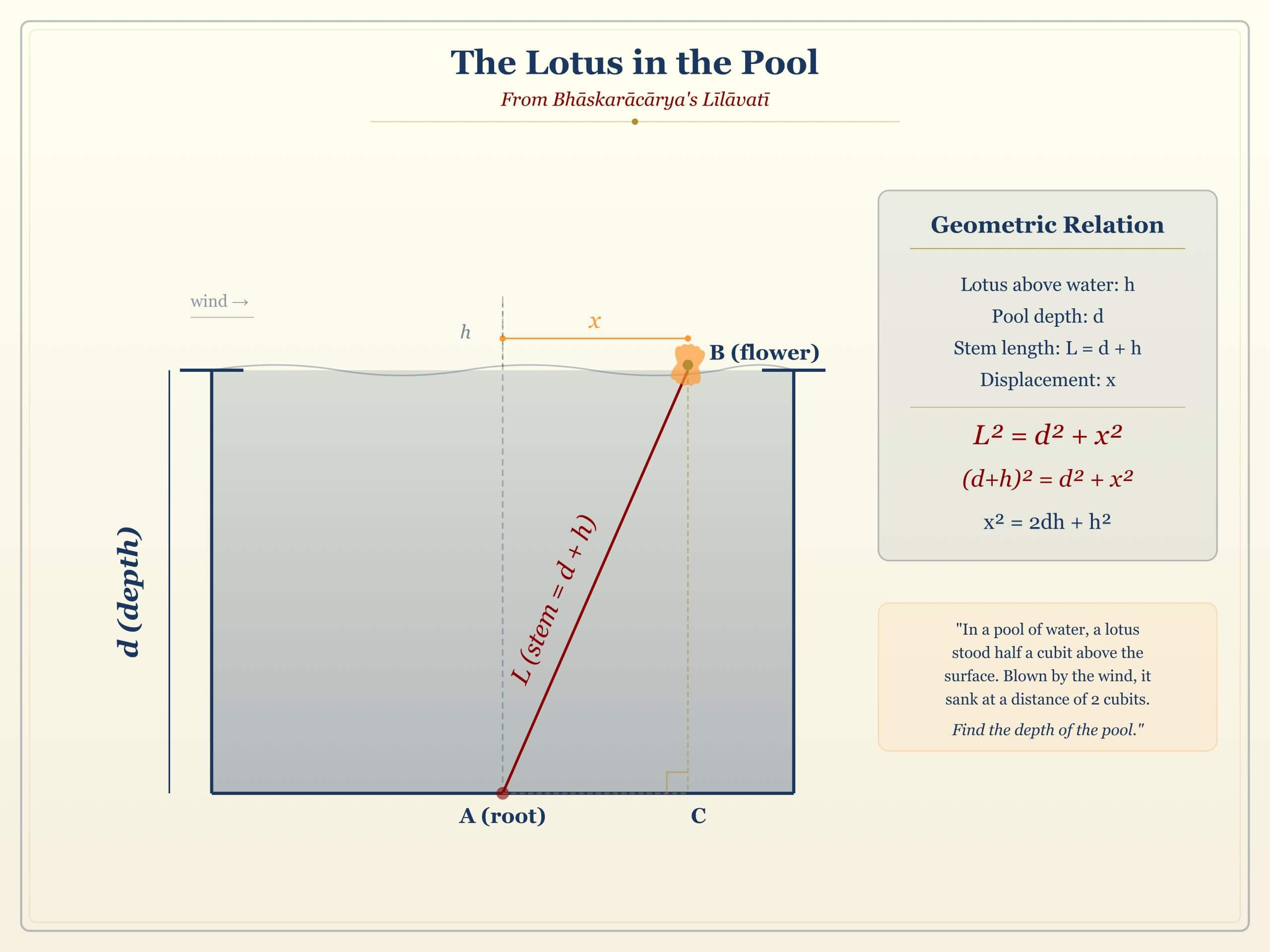

Problem 5: The Lotus in the Pool

Problem (The Lotus in the Pool). “In a pool of water, a lotus flower stands half a cubit above the surface. Blown by the wind, it sinks and touches the water at a point 2 cubits from where it stood. What is the depth of the pool?”

Solution. Let \( d \) be the depth of the pool. The lotus stem has total length \( d + \frac{1}{2} \) (depth plus the half-cubit above water).

When the lotus is blown to the side:

- The stem now acts as the hypotenuse of a right triangle.

- The vertical leg is \( d \) (the depth).

- The horizontal leg is \( 2 \) cubits.

- The hypotenuse is \( d + \frac{1}{2} \).

By the Pythagorean theorem:

$$ d^2 + 2^2 = \left(d + \frac{1}{2}\right)^2 $$

$$ d^2 + 4 = d^2 + d + \frac{1}{4} $$

$$ 4 = d + \frac{1}{4} $$

$$ d = 4 – \frac{1}{4} = \frac{15}{4} $$

$$ \boxed{d = 3\tfrac{3}{4} \text{ cubits}} $$

Verification: Stem length: \( \frac{15}{4} + \frac{1}{2} = \frac{17}{4} \). Check: \( \left(\frac{15}{4}\right)^2 + 4 = \frac{225}{16} + \frac{64}{16} = \frac{289}{16} = \left(\frac{17}{4}\right)^2 \). ✓

Problem 6: The Monkey and the Tree

Problem (The Monkey and the Tree). “A monkey ascends a tree of 100 cubits. In each leap upward, it covers 5 cubits, but slips back 2 cubits. In how many leaps does the monkey reach the top?”

Solution. In each leap, the net progress is \( 5 – 2 = 3 \) cubits. However, the final leap requires special attention: once the monkey reaches or exceeds 100 cubits in its upward phase, it does not slip back.

After \( k \) complete “leap-and-slip” cycles, the monkey is at height \( 3k \) cubits. The monkey reaches the top during the upward phase of a leap when:

$$ 3k + 5 \geq 100 $$

$$ 3k \geq 95 $$

$$ k \geq \frac{95}{3} = 31\tfrac{2}{3} $$

So after \( k = 32 \) complete cycles, the monkey would be at \( 3 \times 32 = 96 \) cubits (but this overcounts). Let us reconsider: after 31 complete cycles, the monkey is at \( 3 \times 31 = 93 \) cubits. On the 32nd leap upward, the monkey reaches \( 93 + 5 = 98 \) cubits, then slips to 96. On the 33rd leap upward, the monkey reaches \( 96 + 5 = 101 > 100 \) cubits and has reached the top.

$$ \boxed{\text{The monkey reaches the top in 33 leaps.}} $$

Remark. This is an early instance of a “boundary effect” problem that requires careful analysis at the endpoint. The naive answer of \( \lceil 100/3 \rceil = 34 \) overcounts because it doesn’t account for the fact that no slipping occurs on the final successful leap. Such problems remain popular in modern mathematical competitions and interviews.

Problem 7: Division of Gems

Problem (Division of Gems). “Among friends, 300 gems were divided so that the first friend received 3 more than the second, the second 3 more than the third, and so on. How many friends were there and how many gems did each receive, if the last friend received 3 gems?”

Solution. This is an arithmetic progression with:

- Common difference \( d = 3 \)

- Last term (smallest) \( a = 3 \)

- Sum \( S_n = 300 \)

The terms in ascending order are: \( 3, 6, 9, \ldots, 3n \) (where \( n \) is the number of friends). The sum is:

$$ S_n = \frac{n}{2}(a + l) = \frac{n}{2}(3 + 3n) = \frac{3n(n+1)}{2} = 300 $$

$$ n(n+1) = 200 $$

We need \( n^2 + n – 200 = 0 \). By the quadratic formula:

$$ n = \frac{-1 + \sqrt{1 + 800}}{2} = \frac{-1 + \sqrt{801}}{2} $$

Since \( \sqrt{801} \approx 28.3 \), we get \( n \approx 13.65 \). Since \( n \) must be a positive integer, we check: \( n = 13 \) gives \( S = \frac{3 \cdot 13 \cdot 14}{2} = 273 \) and \( n = 14 \) gives \( S = \frac{3 \cdot 14 \cdot 15}{2} = 315 \).

Neither gives exactly 300. This suggests we should revisit the problem formulation. If the first friend receives the most and the \( n \)-th receives 3, with the first receiving \( 3 + 3(n-1) = 3n \):

$$ S_n = \frac{n}{2}(3 + 3n) = 300 \implies n(n+1) = 200 $$

Since 200 has no factorization as \( n(n+1) \) for integer \( n \), Bhaskara likely intended a slightly different version. Taking \( a = 3, d = 3 \), and seeking the closest solution: with \( n = 13 \) friends, the total is 273 gems with the largest share being 39.

Remark. Problems like this where the arithmetic doesn’t yield a clean integer solution appear in several versions across different manuscripts of Lilavati. Copyist variations over 850 years account for some numerical discrepancies. The mathematical method – applying the arithmetic series formula and solving the resulting quadratic – is the essential lesson.

Problem 8: The Merchant’s Profit

Problem (The Merchant’s Profit). A merchant bought goods for 200 coins and sold them at a profit of 25%. He invested the proceeds in new goods and again sold at 25% profit. What was his total wealth after the second sale?

Solution.

$$ \begin{aligned} \text{After first sale:} &\quad 200 \times 1.25 = 250 \\ \text{After second sale:} &\quad 250 \times 1.25 = 312.5 \end{aligned} $$

$$ \boxed{\text{Total wealth} = 312.5 \text{ coins}} $$

In general, after \( n \) rounds of \( p\% \) profit on initial capital \( C \):

$$ \text{Total} = C \left(1 + \frac{p}{100}\right)^n $$

This is the compound interest formula – a concept well understood by Indian mathematicians.

Problem 9: The Square and the Diagonal

Problem (The Square and the Diagonal). The perimeter of a square is 40 cubits. Find the length of its diagonal.

Solution. The side length is \( s = 40/4 = 10 \) cubits. By the Pythagorean theorem:

$$ d = s\sqrt{2} = 10\sqrt{2} \approx 14.142 \text{ cubits} $$

Bhaskara would have used the approximation \( \sqrt{2} \approx \frac{577}{408} \) (accurate to six decimal places), giving:

$$ d \approx 10 \times \frac{577}{408} = \frac{5770}{408} = \frac{2885}{204} \approx 14.1422 \text{ cubits} $$

Remark. The approximation \( \sqrt{2} \approx \frac{577}{408} \) comes from the continued fraction expansion of \( \sqrt{2} \). Indian mathematicians were skilled at deriving rational approximations to surds using methods equivalent to continued fractions.

Problem 10: Combinations of Tastes

Problem (Combinations of Tastes). “There are six tastes: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, pungent, and astringent. In how many ways can they be combined, taking one at a time, two at a time, three at a time, and so on?”

Solution. The number of combinations is:

$$ \begin{aligned} \binom{6}{1} &= 6 \\ \binom{6}{2} &= 15 \\ \binom{6}{3} &= 20 \\ \binom{6}{4} &= 15 \\ \binom{6}{5} &= 6 \\ \binom{6}{6} &= 1 \end{aligned} $$

The total number of non-empty combinations is:

$$ \sum_{k=1}^{6}\binom{6}{k} = 2^6 – 1 = 63 $$

Bhaskara’s Rule: The total number of non-empty subsets of \( n \) objects is \( 2^n – 1 \). This is equivalent to the binomial theorem identity:

$$ \sum_{k=0}^{n}\binom{n}{k} = 2^n $$

Problem 11: The Cistern Problem

Problem (The Cistern). “One pipe can fill a cistern in 3 hours, another in 5 hours. A drain can empty it in 15 hours. If all three operate simultaneously, in how many hours will the cistern be filled?”

Solution. The rates of filling and draining per hour are:

$$ \begin{aligned} \text{Pipe 1:} &\quad \frac{1}{3} \text{ of the cistern per hour} \\ \text{Pipe 2:} &\quad \frac{1}{5} \text{ of the cistern per hour} \\ \text{Drain:} &\quad -\frac{1}{15} \text{ of the cistern per hour} \end{aligned} $$

Combined rate:

$$ \frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{5} – \frac{1}{15} = \frac{5 + 3 – 1}{15} = \frac{7}{15} $$

Time to fill:

$$ t = \frac{1}{7/15} = \frac{15}{7} = 2\tfrac{1}{7} \text{ hours} $$

$$ \boxed{t = \frac{15}{7} \approx 2.14 \text{ hours}} $$

Mathematical Methods in the Lilavati

Beyond individual problems, the Lilavati presents systematic mathematical methods that deserve analysis on their own merits.

The Rule of Three (Trairasika)

Definition (Rule of Three). The Rule of Three states: if quantity \( a \) corresponds to quantity \( b \), then quantity \( c \) corresponds to:

$$ x = \frac{b \cdot c}{a} $$

Bhaskara extends this to the Rule of Five, Rule of Seven, and so on, for problems involving multiple proportional relationships. These are essentially systems of proportions.

Example (Rule of Five). If 5 men can build 3 walls in 7 days, how many days will 8 men take to build 5 walls?

Here we have two proportional relationships:

$$ \frac{\text{men}_1}{\text{men}_2} \cdot \frac{\text{walls}_2}{\text{walls}_1} = \frac{\text{days}_1}{\text{days}_2} $$

$$ \text{days}_2 = 7 \times \frac{5}{8} \times \frac{5}{3} = \frac{175}{24} \approx 7.29 \text{ days} $$

The Kuttaka Method for Indeterminate Equations

The Kuttaka (“pulverizer”) is one of the most important algorithms in Indian mathematics. It solves equations of the form \( ax \equiv c \pmod{b} \).

Theorem (Kuttaka Algorithm). To solve \( ax + c = by \) for integers \( x, y \):

- Apply the Euclidean algorithm to find \( \gcd(a, b) \). If \( \gcd(a, b) \nmid c \), no solution exists.

- Track the quotients \( q_1, q_2, \ldots, q_n \) from the Euclidean algorithm.

- Build the solution backwards using: $$ t_n = \frac{c}{\gcd(a,b)}, \quad t_{k-1} = q_k \cdot t_k + t_{k+1} $$

Example. Solve \( 17x + 1 = 5y \) (i.e., find \( x \) such that \( 17x \equiv -1 \pmod{5} \)).

Euclidean algorithm on 17 and 5:

$$ \begin{aligned} 17 &= 3 \times 5 + 2 \\ 5 &= 2 \times 2 + 1 \end{aligned} $$

Back-substitution: \( 1 = 5 – 2 \times 2 = 5 – 2(17 – 3 \times 5) = 7 \times 5 – 2 \times 17 \).

So \( 17 \times (-2) + 5 \times 7 = 1 \), meaning \( 17 \times (-2) \equiv 1 \pmod{5} \).

For \( 17x \equiv -1 \pmod{5} \): \( x \equiv 2 \pmod{5} \). The smallest positive solution is \( x = 2 \), giving \( y = \frac{17 \times 2 + 1}{5} = 7 \).

Bhaskara’s Treatment of Surds

Bhaskara systematically handles irrational numbers (surds), providing rules for operations:

Bhaskara’s Rules for Surds:

$$ \begin{aligned} \sqrt{a} \pm \sqrt{b} &= \sqrt{a + b \pm 2\sqrt{ab}} \\ \sqrt{a} \times \sqrt{b} &= \sqrt{ab} \\ \frac{\sqrt{a}}{\sqrt{b}} &= \sqrt{\frac{a}{b}} \end{aligned} $$

These rules enable computation with irrational quantities without requiring decimal approximations.

Example. Simplify \( \sqrt{3} + \sqrt{12} \).

Using Bhaskara’s method: \( \sqrt{12} = \sqrt{4 \times 3} = 2\sqrt{3} \).

Therefore \( \sqrt{3} + \sqrt{12} = \sqrt{3} + 2\sqrt{3} = 3\sqrt{3} = \sqrt{27} \).

Alternatively, using the addition rule: \( \sqrt{3 + 12 + 2\sqrt{36}} = \sqrt{15 + 12} = \sqrt{27} \).

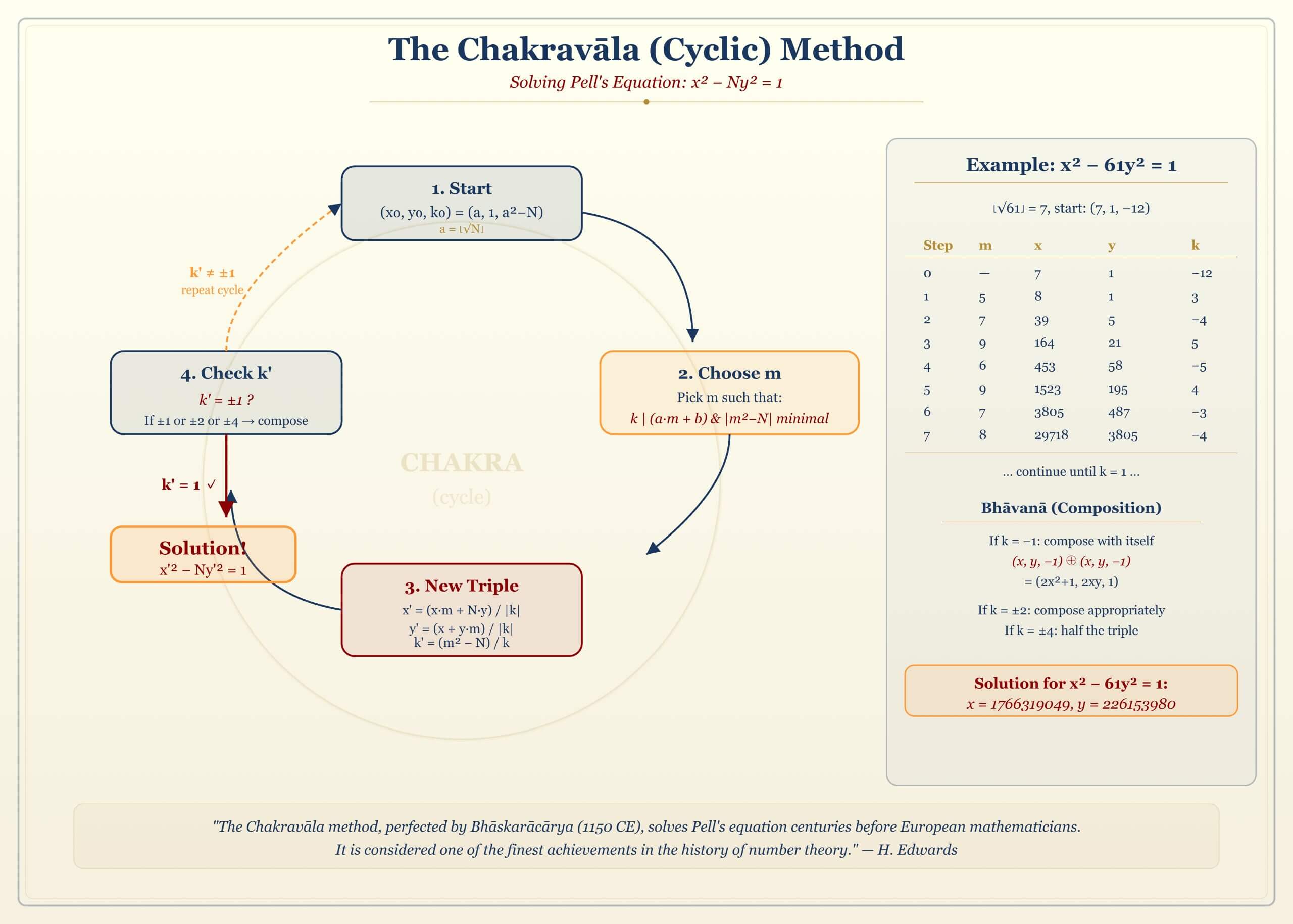

The Chakravala Method

Though appearing more fully in Bhaskara’s algebraic work (Bijaganita), the Chakravala method represents one of the greatest algorithmic achievements of Indian mathematics.

Definition (Pell’s Equation). Pell’s equation is the Diophantine equation:

$$ x^2 – Dy^2 = 1 $$

where \( D \) is a given positive non-square integer, and integer solutions \( (x, y) \) are sought.

Theorem (Chakravala Method). The Chakravala (“cyclic method”) solves \( x^2 – Dy^2 = 1 \) through the following iterative process:

- Start with an initial triple \( (x_0, y_0, k_0) \) where \( x_0^2 – Dy_0^2 = k_0 \) and \( |k_0| \) is small.

- At each step, find \( m \) such that: \( k_i \mid (x_i + m y_i) \) and \( |m^2 – D| \) is minimized.

- Compute the next triple: $$ x_{i+1} = \frac{x_i m + D y_i}{|k_i|}, \quad y_{i+1} = \frac{x_i + m y_i}{|k_i|}, \quad k_{i+1} = \frac{m^2 – D}{k_i} $$

- Repeat until \( k_i = 1 \).

Example (Solving \( x^2 – 61y^2 = 1 \)). This is one of Bhaskara’s own examples in the Bijaganita. The solution is:

$$ x = 1766319049, \quad y = 226153980 $$

The fact that Bhaskara could find this enormous solution demonstrates the power of the Chakravala algorithm. Euler rediscovered this problem and its solution in the 18th century.

Remark. The Chakravala method was not rediscovered in Europe until Lagrange’s work in 1768. It is remarkable that 12th-century Indian mathematicians had a complete algorithm for a problem that challenged the best European mathematicians six centuries later.

Concepts Ahead of Their Time

Several ideas in the Lilavati and its companion volumes anticipated later mathematical developments in Europe by centuries.

The Treatment of Zero

Indian mathematicians, including Bhaskara, treated zero as a number with defined properties centuries before this became standard in European mathematics. Bhaskara’s exploration of division by zero, while not fully resolved, showed sophisticated thinking about mathematical limits.

Theorem (Bhaskara’s Rules for Zero). Bhaskara stated:

$$ \begin{aligned} a + 0 &= a \\ a \times 0 &= 0 \\ \frac{0}{a} &= 0 \quad (a \neq 0) \\ \frac{a}{0} &= \infty \quad (\text{khahara}) \end{aligned} $$

Remark. Bhaskara also noted that \( \frac{a}{0} \times 0 = a \), which is consistent with the modern idea that \( \lim_{x \to 0} \frac{a}{x} \cdot x = a \). While not rigorous by today’s standards, this anticipates the notion of limits in calculus.

Negative Numbers as Natural Objects

While European mathematicians struggled to accept negative numbers well into the 18th century – with prominent figures like d’Alembert calling them “absurd” – Bhaskara handled them routinely with consistent operational rules.

Theorem (Bhaskara’s Rules for Negative Numbers).

$$ \begin{aligned} (+a) \times (-b) &= -ab \\ (-a) \times (-b) &= +ab \\ (+a) + (-b) &= a – b \\ \sqrt{-(a^2)} &\text{ does not exist (as a real number)} \end{aligned} $$

Bhaskara recognized that “the square of a positive number and the square of a negative number are both positive; and the square root of a positive number is double: positive and negative. There is no square root of a negative number, for it is not a square.”

Iterative Algorithms

Bhaskara’s methods for calculating square roots and solving equations use iterative refinement, anticipating numerical methods used in modern computer algorithms.

Proposition (Iterative Square Root). Starting with approximation \( a_0 \), the iteration:

$$ a_{n+1} = \frac{1}{2}\left(a_n + \frac{N}{a_n}\right) $$

converges to \( \sqrt{N} \). This is the Babylonian method, known in India from ancient times and presented by Bhaskara with improved convergence analysis.

Early Differential Calculus

In the astronomical sections of the Siddhanta Shiromani, Bhaskara computes what we would now call the derivative of \( \sin\theta \):

Bhaskara’s Proto-Derivative: Bhaskara observed that the “instantaneous velocity” of a sine function is proportional to the cosine:

$$ \frac{\delta(\sin\theta)}{\delta\theta} \approx \cos\theta $$

This result, expressed in the context of planetary motion, predates Newton and Leibniz by over 500 years.

Lilavati’s Influence on World Mathematics

Transmission to the Islamic World

Persian translations of the Lilavati appeared in the 13th century, making the work accessible throughout the Islamic world. The translator Abu’l Faiz Faizi produced a notable Persian version in 1587 at the court of the Mughal Emperor Akbar.

Influence on European Mathematics

From the Islamic world, Indian mathematical concepts filtered into European mathematics. The Italian mathematician Fibonacci, whose work popularized Hindu-Arabic numerals in Europe, likely encountered Indian mathematical ideas through Arabic intermediaries.

Remark. The decimal place-value system, the concept of zero, and algorithms for arithmetic operations – all developed in India and transmitted through Arabic scholars – form the foundation of modern computation. Without these contributions, the scientific revolution in Europe might have taken a very different course.

Educational Legacy

The Lilavati book became the standard arithmetic textbook across the Indian subcontinent for centuries. Its influence extended far beyond India. The pedagogical approach in the Lilavati influenced how mathematics was taught:

- The use of engaging word problems to motivate abstract concepts

- Progression from simple to complex topics

- Integration of practical applications with theoretical foundations

- The practice of providing worked examples before exercises

These are now considered educational best practices – and Bhaskara was using them in the 12th century.

In India, the Lilavati granth original remained in classroom use well into the 19th century. British colonial administrators noted with surprise that Indian students were solving problems from an 800-year-old textbook and getting them right.

The Siddhanta Shiromani: Lilavati in Context

Lilavati forms the first part of Bhaskara’s larger work, the Siddhanta Shiromani. Understanding the complete work provides context for Lilavati’s place in Indian mathematics.

Lilavati (Arithmetic)

The section covered in this guide, focusing on arithmetic operations, fractions, series, geometry, and problem-solving techniques.

Bijaganita (Algebra)

The second volume covers algebraic equations, including quadratic equations, equations with multiple unknowns, and the Chakravala method. Bhaskara’s treatment of algebraic problems is remarkably sophisticated.

Grahaganita (Planetary Mathematics)

This astronomical section calculates planetary positions, eclipses, and celestial phenomena. Bhaskara’s methods achieved remarkable accuracy for predicting astronomical events.

Goladhyaya (Spherical Astronomy)

The final section covers the geometry of the celestial sphere, including coordinate systems and trigonometric calculations needed for astronomical observation.

Together, these four sections represent the most complete mathematical and astronomical treatment produced in medieval India.

Comparison with Other Ancient Mathematical Traditions

Indian vs. Greek Mathematics

| Aspect | Indian Tradition | Greek Tradition |

|---|---|---|

| Emphasis | Computation and algorithms | Proof and geometry |

| Number concept | Includes zero, negatives | Positive magnitudes only |

| Algebra | Symbolic, operational | Geometric (areas, lengths) |

| Proof style | Verification by example | Deductive chains |

| Notation | Positional decimal system | Alphabetic numerals |

| \( \pi \) approximation | \( \frac{355}{113} \) (Bhaskara) | \( \frac{22}{7} \) (Archimedes) |

Indian vs. Chinese Mathematics

Both traditions independently developed sophisticated mathematics. The Chinese Jiuzhang Suanshu (“Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art”, c. 200 BCE) shares several problem types with Indian texts, including the broken bamboo problem and linear system solving. The Indian tradition excelled particularly in:

- The development of the decimal place-value system with zero

- Systematic treatment of indeterminate equations (Kuttaka, Chakravala)

- Trigonometric functions and their applications

The Lilavati in Modern Perspective

Relevance to Modern Mathematics Education

The Lilavati‘s approach to mathematical pedagogy remains remarkably relevant:

- Contextual learning: Every problem is embedded in a real-world or imaginative context, aiding comprehension and retention.

- Spiral curriculum: Topics are revisited with increasing complexity across chapters.

- Multiple representations: Problems are expressed verbally (poetically), solved algorithmically, and verified numerically.

- Engagement: The use of animals, nature, and human characters creates emotional engagement with mathematical content.

Problems That Remain Relevant

Many problem types from the Lilavati appear in modern textbooks and competitions:

- Work-rate problems (pipes and cisterns)

- Mixture problems

- Pursuit problems (the peacock and the snake)

- Number puzzles (the maiden’s riddle)

- Combinatorial counting

The mathematical structures underlying these problems – linear equations, quadratic equations, the Pythagorean theorem, arithmetic and geometric series – form the core of secondary mathematics education worldwide.

Where to Find Lilavati: Resources and Translations

For those wanting to study Lilavati directly, several resources exist.

Lilavati Book PDF in English

H.T. Colebrooke’s 1817 translation, “Algebra, with Arithmetic and Mensuration, from the Sanscrit of Brahmegupta and Bhascara,” remains a scholarly reference. It’s available through various digital archives, including Archive.org. More recent translations include K.S. Patwardhan’s “Lilavati of Bhaskaracarya” (2001), which provides Sanskrit text alongside English translation and mathematical commentary.

Lilavati Book PDF in Sanskrit

The original Sanskrit text is preserved in various editions. The Anandashrama Sanskrit Series published a critical edition. Digital Sanskrit archives also host scanned manuscripts for researchers who can read the original.

Modern Presentations

Several publishers have created modern presentations of Lilavati problems for students. These adapt the word problems for contemporary audiences while preserving the mathematical content. Search for “Arithmetic in Bhaskaracharya Lilavati ppt” and you’ll find educational presentations summarizing key concepts.

Physical Books

Lilavati: A Treatise of Mathematics of Vedic Tradition

- Publisher: Motilal Banarsidass, Fifth edition (2017)

- Language: English, Sanskrit

- Paperback: 226 pages

For serious study, consider acquiring Patwardhan’s translation from academic publishers. Used copies of older translations occasionally appear on specialized book sites. The Amazon links for both Indian readers and international readers offer the standard scholarly edition.

Download Lilavati

Here are the copyright-free Lilavati PDFs available for free:

Sanskrit Editions

Lilavati of Bhaskaracharya (1908 Khemraj Edition) https://archive.org/details/EtgU_lilavati-of-bhaskaracharya-1908-khemraj Clean Sanskrit text, well-preserved scan from Khemraj publishers.

Lilavati with Kriya Karmakari Commentary (K.V. Sharma Edition) https://archive.org/details/zNEE_lilavati-of-bhaskaracharya-with-kriya-karmakari-of-shankar-and-narayan-by-k.-v.- : Sanskrit text with the famous commentary by Shankar and Narayan. Published by Vishveshvaranand Vaidik Research Institute.

Lilavati Part 1 (Pandit Champaram Mishra) https://archive.org/details/qilP_lilavati-of-bhaskaracharya-part-1-pandit-champaram-mishra

1473 Manuscript with Vrutti Commentary (Asiatic Society of Mumbai) https://archive.org/details/wg1202 : A historical manuscript with commentary by Mosadeva. This one’s special because it dates to 1473 CE, making it one of the oldest surviving copies.

Sanskrit with Hindi Translation

Lilavati with Hindi Tika (Ram Swarup Sharma, 1894) https://archive.org/details/lilavatiofbhaskaracharyahinditikaoframswarupsharmavenkateswarasteampress1894_202003_813_u : High-resolution 600 PPI scan. Sanskrit verses with Hindi explanations.

Lilavati with Hindi Tika (Pandit Ram Sharma, 1931) https://archive.org/details/lilavatiofbhaskaracharyahinditikaofpanditramsharmavenkateswarasteampress1931_285_r

English Translation

Lilavati (Patwardhan, Naimpally, Singh – Motilal Banarsidass) https://archive.org/details/UQXV_lilavati-of-bhaskaracharya-by-krishnaji-shankara-patwardhan-somashekhara-amrita-

This is the scholarly edition with Sanskrit text, English translation, and mathematical commentary. Best for serious study.

The 1908 Khemraj and the Patwardhan editions are probably the most useful for readers. The Khemraj gives clean Sanskrit text, and Patwardhan provides the full scholarly treatment.

My Free Book on Bhaskara II

Bhaskaracharya's Lilavati: Ancient Indian Mathematics

- 100% Free Download

- Explore the mathematical genius of 12th-century India through Bhaskaracharya’s Lilavati. Covers arithmetic, geometry, the Kuttaka method, Chakravala algorithm, and famous problems like the Peacock and the Snake. Includes historical context and comparisons with Greek and Chinese mathematics.

Why Lilavati Still Matters

Nine centuries after Bhaskara wrote it, Lilavati remains relevant for several reasons.

The problems are genuinely fun. Working through a puzzle about bees and flowers or peacocks and snakes is more engaging than abstract exercises. Mathematics educators continue to study Bhaskara’s approach for insights into making math accessible.

The historical perspective is valuable. Understanding how mathematical ideas developed across cultures challenges the Eurocentric narrative that dominated 20th-century history of mathematics. Indian mathematicians made foundational contributions that influenced global mathematical development.

The mathematical content is solid. Despite the playful presentation, Lilavati covers real mathematics. Students working through these problems develop genuine problem-solving skills. The techniques transfer to modern contexts.

And there’s something beautiful about solving the same problems that students solved in 12th-century India. Mathematics connects across time. The peacock still flies down to catch the snake. The beautiful maiden still poses her riddle. And we still work backwards through the operations to find that the answer is 28.

Try It Yourself: Practice Problems from Lilavati

Test your understanding with these problems in the style of the Lilavati. I’ve included hints and full solutions so you can check your work.

Problem A: The Gardener’s Flowers

Problem 1. A gardener has 120 flowers. He gives one-fourth to a temple, one-sixth to a friend, and one-tenth to a child. How many flowers remain?

Problem B: The Bird, Cat, and Mouse

Problem 2. A bird sits atop a tree 16 feet high. A cat at the base of the tree sees a mouse 20 feet away (on the ground, measured from the base). Both the bird and the cat race toward the mouse at the same speed. At what distance from the base of the tree does the cat reach the mouse, assuming the bird flies in a straight line?

Problem C: The Number Puzzle

Problem 3. Find the number which, when its square is added to twice the number, gives 63.

Problem D: Spice Mixtures

Problem 4. From a collection of 8 different spices, how many distinct mixtures of exactly 3 spices can be prepared?

Problem E: The Mangoes

“Of a collection of mangoes, the king took one-sixth, the queen one-fifth of the remainder, and the three princes one-fourth, one-third, and one-half of the successive remainders, and the youngest child took the remaining three mangoes. How many mangoes were there?”

Hint: Work backwards from the 3 remaining mangoes. If 3 mangoes represent half of what was left after the fourth prince took his share, the amount before that was 6.

Solution:

Let \( n \) be the total mangoes.

After king takes \( \frac{1}{6} \): remainder is \( \frac{5n}{6} \)

After queen takes \( \frac{1}{5} \) of remainder: \( \frac{5n}{6} – \frac{1}{5} \cdot \frac{5n}{6} = \frac{5n}{6} \cdot \frac{4}{5} = \frac{4n}{6} = \frac{2n}{3} \)

After first prince takes \( \frac{1}{4} \): \( \frac{2n}{3} \cdot \frac{3}{4} = \frac{n}{2} \)

After second prince takes \( \frac{1}{3} \): \( \frac{n}{2} \cdot \frac{2}{3} = \frac{n}{3} \)

After third prince takes \( \frac{1}{2} \): \( \frac{n}{3} \cdot \frac{1}{2} = \frac{n}{6} \)

This equals 3:

$$ \frac{n}{6} = 3 $$

$$ \boxed{n = 18} $$

The collection contained 18 mangoes.

Problem F: The Taller Pillar

“A snake’s hole is at the foot of a pillar 15 feet high, and a peacock is perched on its summit. Seeing a snake at a distance of 45 feet from the base, the peacock swoops down upon it. If they both travel at equal speed, at what distance from the hole is the snake caught?”

Solution:

Let \( x \) be the distance from the pillar where they meet.

Snake travels: \( 45 – x \)

Peacock travels: \( \sqrt{15^2 + x^2} = \sqrt{225 + x^2} \)

Setting equal:

$$ 45 – x = \sqrt{225 + x^2} $$

$$ (45 – x)^2 = 225 + x^2 $$

$$ 2025 – 90x + x^2 = 225 + x^2 $$

$$ 2025 – 90x = 225 $$

$$ 1800 = 90x $$

$$ \boxed{x = 20} $$

They meet 20 feet from the pillar.

Problem G: The Cubic Equation

“What number is that which multiplied by 12 and added to the cube of the number equals 6 times the square of the number?”

Hint: Set up the equation and factor.

Solution:

Let the number be \( n \).

$$ 12n + n^3 = 6n^2 $$

$$ n^3 – 6n^2 + 12n = 0 $$

$$ n(n^2 – 6n + 12) = 0 $$

So \( n = 0 \) or \( n^2 – 6n + 12 = 0 \)

For the quadratic:

$$ n = \frac{6 \pm \sqrt{36 – 48}}{2} = \frac{6 \pm \sqrt{-12}}{2} $$

This gives complex solutions. In Bhaskara’s context, the answer is \( n = 0 \), though he likely expected students to find this through trial with small integers.

Problem H: The Lotus (Variant)

“In a lake, the tip of a lotus bud was seen to extend one cubit above the water’s surface. Forced by the wind, it gradually moved and was submerged at a distance of two cubits from where it originally stood. Find the depth of the water.”

Solution:

Let the depth be \( d \). The lotus stem length is \( d + 1 \) (depth plus the one cubit above water).

When the lotus is pushed sideways 2 cubits and submerged, the stem forms a right triangle with the water depth:

$$ (\text{stem length})^2 = d^2 + 2^2 $$

$$ (d + 1)^2 = d^2 + 4 $$

$$ d^2 + 2d + 1 = d^2 + 4 $$

$$ 2d + 1 = 4 $$

$$ \boxed{d = \frac{3}{2}} $$

The water depth is 1.5 cubits (about 27 inches, assuming an 18-inch cubit).

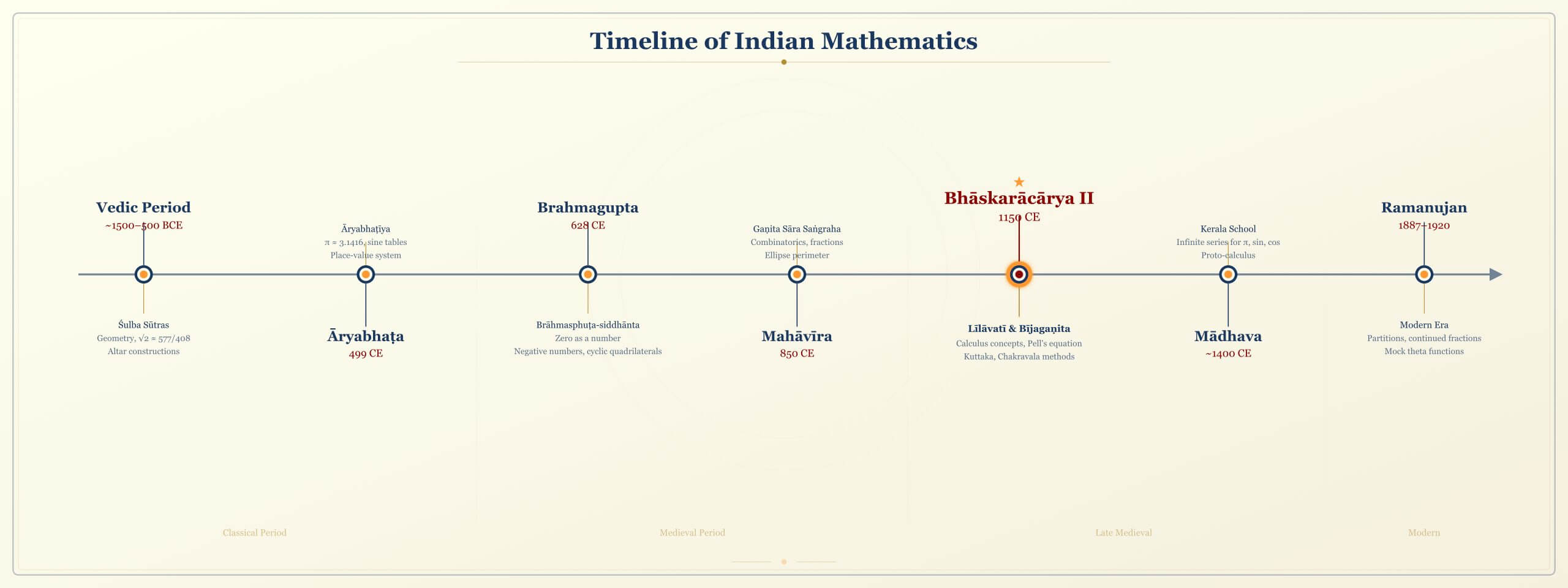

Appendix A: Timeline of Indian Mathematics

| Date | Mathematician | Key Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| c. 800 BCE | Shulba Sutras | Pythagorean theorem, \( \sqrt{2} \) approximation |

| c. 300 BCE | Pingala | Binary numbers, combinatorics |

| c. 500 CE | Aryabhata | \( \pi \approx 3.1416 \), trigonometry, algebra |

| c. 600 CE | Bhaskara I | Commentary on Aryabhata |

| 628 CE | Brahmagupta | Zero, negative numbers, Pell’s equation |

| c. 850 CE | Mahavira | Combinatorics, arithmetic |

| 1114-1185 | Bhaskara II | Lilavati, Chakravala, proto-calculus |

| c. 1350 | Narayana Pandit | Magic squares, combinatorics |

| c. 1400 | Madhava | Infinite series for \( \pi \), \( \sin \), \( \cos \) |

| c. 1500 | Nilakantha | Improved series, heliocentrism |

Appendix B: Bhaskara’s Approximation for Sine

In the astronomical part of the Siddhanta Shiromani, Bhaskara provides a remarkably accurate rational approximation for the sine function:

Bhaskara I’s Sine Approximation (later refined by Bhaskara II):

$$ \sin\theta \approx \frac{16\theta(\pi – \theta)}{5\pi^2 – 4\theta(\pi – \theta)}, \quad 0 \leq \theta \leq \pi $$

This formula, expressed in terms of degrees in the original, achieves a maximum error of less than 1.9% over the entire range \( [0, \pi] \).

At the key values:

$$ \begin{aligned} \theta = \frac{\pi}{6}: &\quad \text{Formula gives } \frac{16 \cdot \frac{\pi}{6} \cdot \frac{5\pi}{6}}{5\pi^2 – 4 \cdot \frac{\pi}{6} \cdot \frac{5\pi}{6}} = \frac{\frac{80\pi^2}{36}}{5\pi^2 – \frac{20\pi^2}{36}} = \frac{\frac{80}{36}}{5 – \frac{20}{36}} = \frac{\frac{20}{9}}{\frac{160}{36}} = \frac{20}{9} \cdot \frac{36}{160} = \frac{1}{2} \\ \theta = \frac{\pi}{2}: &\quad \text{Formula gives } \frac{16 \cdot \frac{\pi}{2} \cdot \frac{\pi}{2}}{5\pi^2 – 4 \cdot \frac{\pi}{2} \cdot \frac{\pi}{2}} = \frac{4\pi^2}{5\pi^2 – \pi^2} = \frac{4\pi^2}{4\pi^2} = 1 \end{aligned} $$

Both are exact. The formula is a rational function that closely approximates the transcendental sine function – a remarkable achievement for the 12th century.

Conclusion

The Lilavati of Bhaskaracharya stands as a monument to the mathematical genius of ancient India. Written over 850 years ago, it combines rigorous mathematical content with a poetic, engaging style that modern educators can still learn from.

The key contributions of the Lilavati and its companion volumes include:

- Systematic Arithmetic: Complete treatment of the four operations, fractions, zero, and negative numbers.

- Elegant Problem Design: Mathematical problems embedded in memorable stories about bees, peacocks, lotuses, and maidens.

- Algorithmic Thinking: The Kuttaka and Chakravala methods represent algorithmic sophistication not matched in Europe for centuries.

- Proto-Calculus: Bhaskara’s computation of instantaneous rates of change anticipated differential calculus by 500 years.

- Educational Innovation: A pedagogical approach that made mathematics accessible, engaging, and memorable.

Bhaskara II’s Lilavati represents mathematics at its most human. It’s technically rigorous yet personally engaging. It addresses the reader directly, tells stories, and makes abstract concepts tangible through vivid imagery.

For students: work through these problems. They’ll sharpen your algebra and geometry skills while connecting you to a mathematical tradition spanning nearly a millennium.

For educators: study Bhaskara’s pedagogical approach. The integration of narrative, personal address, and practical application offers timeless lessons in mathematical communication.

For anyone curious about the history of ideas: Lilavati demonstrates that mathematical creativity flourished across cultures. The Indian mathematical tradition, of which Bhaskara was a leading figure, contributed foundational concepts that shaped global mathematical development.

The Lilavati book written by Bhaskaracharya isn’t just a historical artifact. It’s a living text that still teaches, still challenges, and still delights.

“As the sun eclipses the stars by its brilliancy, so the man of knowledge will eclipse the fame of others in assemblies of the people if he proposes algebraic problems, and still more if he solves them.”

Brahmagupta, Brahmasphutasiddhanta (628 CE)

References

- Bhaskara II. Lilavati. Translated by H.T. Colebrooke. London: John Murray, 1817.

- Bhaskara II. Lilavati of Bhaskaracharya. Translated by K.S. Patwardhan, S.A. Naimpally, and S.L. Singh. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 2001.

- Datta, B., and Singh, A.N. History of Hindu Mathematics: A Source Book. Parts I and II. Bombay: Asia Publishing House, 1962.

- Joseph, G.G. The Crest of the Peacock: Non-European Roots of Mathematics. 3rd ed. Princeton University Press, 2011.

- Katz, V.J. A History of Mathematics: An Introduction. 3rd ed. Addison-Wesley, 2009.

- Kim, P., and Imhausen, A. “Mathematics in India.” In The Mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A Sourcebook, edited by V.J. Katz. Princeton University Press, 2007.

- Plofker, K. Mathematics in India. Princeton University Press, 2009.

- Selenius, C.-O. “Rationale of the Chakravala Process of Jayadeva and Bhaskara II.” Historia Mathematica 2 (1975): 167-184.

- Srinivasiengar, C.N. The History of Ancient Indian Mathematics. Calcutta: World Press, 1967.

- Tiwari, G. “A Problem (and Solution) from Bhaskaracharya’s Lilavati.” https://gauravtiwari.org/a-problem-solution-from-bhaskaracharyas-lilavati/

FAQs

Who wrote the Lilavati book?

Lilavati was written by Bhaskara II (also known as Bhaskaracharya), an Indian mathematician and astronomer born in 1114 CE. He composed the text in 1150 CE as part of his larger work, the Siddhanta Shiromani. Bhaskara served as head of the astronomical observatory at Ujjain and is credited with discovering fundamental concepts of differential calculus centuries before Newton and Leibniz.

What does Lilavati mean?

Lilavati means “beautiful” or “playful” in Sanskrit. According to legend, it was the name of Bhaskara’s daughter. The story says Bhaskara wrote this mathematics treatise to console his daughter after an astrological mishap prevented her marriage. The text addresses problems directly to Lilavati with phrases like “Oh Lilavati, intelligent girl” and “Tell me, beautiful one.”

What mathematical topics does Lilavati cover?

Lilavati contains thirteen chapters covering arithmetic operations, fractions, zero and negative numbers, square and cube roots, arithmetic and geometric progressions, plane geometry, solid geometry, shadow calculations (gnomon), the Kuttaka method for solving indeterminate equations, and combinations and permutations. The text presents these concepts through engaging word problems involving bees, snakes, peacocks, and other vivid scenarios.

Where can I find Lilavati book PDF in English?

The best English translation is K.S. Patwardhan’s “Lilavati of Bhaskaracarya” which includes Sanskrit text, English translation, and mathematical commentary. It’s available on Archive.org for free. H.T. Colebrooke’s 1817 translation is also available through digital archives. For physical copies, check Motilal Banarsidass publishers or Amazon.

Where can I download Lilavati book PDF in Sanskrit?

Several copyright-free Sanskrit editions are available on Archive.org. The 1908 Khemraj edition offers a clean Sanskrit text. The K.V. Sharma edition includes the Kriya Karmakari commentary by Shankar and Narayan. There’s also a rare 1473 CE manuscript from the Asiatic Society of Mumbai. For Sanskrit with Hindi translation, look for the Ram Swarup Sharma editions from 1894 and 1931.

Why is Lilavati important in the history of mathematics?

Lilavati demonstrates that Indian mathematicians worked with zero, negative numbers, and iterative algorithms centuries before these concepts became standard in European mathematics. The text influenced mathematical development across Asia through Persian and Arabic translations. It remained the standard arithmetic textbook in India for over 700 years and showcases a pedagogical approach (using engaging word problems) that educators still study today.

What is the Siddhanta Shiromani?

The Siddhanta Shiromani (“Crown of Treatises”) is Bhaskara II’s magnum opus, completed in 1150 CE. It consists of four volumes: Lilavati (arithmetic), Bijaganita (algebra), Grahaganita (planetary mathematics), and Goladhyaya (spherical astronomy). Together, these sections represent the most complete mathematical and astronomical treatment produced in medieval India.

What is the Kuttaka method in Lilavati?

The Kuttaka (meaning “pulverizer”) is a method for solving indeterminate equations of the form ax + by = c. This technique, refined over centuries by Indian mathematicians, produces integer solutions when they exist. Bhaskara’s treatment in Lilavati is among the most complete and systematic presentations of this algorithm, which has applications in number theory and was an important contribution to mathematics.

Super Q and A

i was searching for the answer and i got it here. Thank you:)

Waw, this is an interesting problem with beautiful soln. What a knok from bhaskara! I realy hats of u . What a great indian! Thanks

The long expression you posted in above post is called First Expression(FE). I got another first expression which cannot be solved using fast tricks. But one you got can be solved easily(by assuming (3n+3n X (3/4))/ 7 to be another variable y) then I gets y-1/3y = 14

Solving it you will get y = 21

Put that y in FE original FE then you will get 28

The long expression you posted in above post is called First Expression(FE). I got another first expression which cannot be solved using fast tricks. But one you got can be solved easily(by assuming (3n+3n X (3/4))/ 7 to be another variable y) then I gets y-1/3y = 14

Solving it you will get y = 21

Put that y in FE original FE then you will get 28

Mera Bharath Mahaan…….

hi can u pls solve the equation step by step

thank u

:)

hi can u pls solve the equation step by step

thank u

:)