The Area of a Disk

The area of a disk with radius \( R \) is \( \pi R^2 \).

You probably memorized this in middle school. But do you know why it’s true?

Most people don’t. They just accept it. And that’s a shame, because the derivation is beautiful. It shows you how calculus and geometry connect. It shows you how ancient mathematicians thought about infinity before calculus even existed.

I’m going to show you two completely different ways to prove this formula. One uses calculus. One predates calculus by two thousand years. Both arrive at the same answer.

First: Disk vs. Circle

Let’s clear up some terminology that trips people up.

A circle is just the boundary. The round edge. It’s a one-dimensional curve with no interior.

A disk is the filled-in region. The whole thing, boundary included. It’s a two-dimensional object with actual area.

When we talk about “the area of a circle,” we really mean the area of a disk. The circle itself has zero area (it’s just a line). But nobody says “area of a disk” in everyday speech, so I’ll use both terms interchangeably. Just know the distinction exists.

What Radius Actually Means

The radius \( R \) is the distance from the center of the disk to any point on its edge.

That word “any” is important. Pick any point on the circumference. The distance to the center is always \( R \). That’s what makes a circle a circle. Every point on the boundary is equidistant from the center.

The area of a disk measures how much surface the disk covers. How many unit squares could you fit inside? The answer, as we’ll prove, is exactly \( \pi R^2 \) square units.

Derivation 1: The Calculus Approach

Here’s the modern way to find the area. It uses integration, which is really just a fancy way of adding up infinitely many infinitely small pieces.

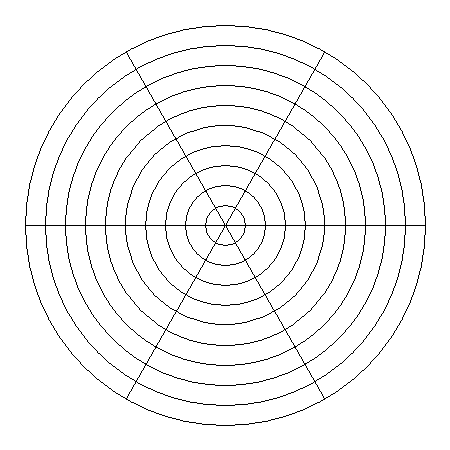

Imagine slicing the disk into thin concentric rings. Like the rings of a tree trunk, but perfectly circular. Each ring has a different radius, ranging from 0 at the center to \( R \) at the edge.

Pick an arbitrary ring at distance \( x \) from the center. Make it incredibly thin, with thickness \( dx \). What’s the area of this ring?

Think about it. If you cut the ring and unroll it, you get a thin rectangle. The length is the circumference of the ring, which is \( 2\pi x \). The width is the thickness \( dx \). So the area of this thin ring is approximately \( 2\pi x \, dx \).

Now add up all these rings from \( x = 0 \) to \( x = R \):

$$A = \int_0^R 2\pi x \, dx$$

This is a straightforward integral. The antiderivative of \( 2\pi x \) is \( \pi x^2 \). Evaluate from 0 to \( R \):

$$A = \pi x^2 \Big|_0^R = \pi R^2 – \pi(0)^2 = \pi R^2$$

Done. The area of a disk is \( \pi R^2 \).

That’s the calculus proof. Clean, quick, and completely unsatisfying if you want to understand what’s really happening. Calculus feels like magic when you first learn it. But it’s built on intuitions that go back to the ancient Greeks.

Derivation 2: The Method of Exhaustion

This is how mathematicians proved the area formula before calculus existed. Archimedes used this approach around 250 BC. It’s called the “method of exhaustion” because you exhaust the area by filling it with shapes you can measure.

The idea: approximate the disk with polygons. Use more and more sides. Watch what happens as the number of sides approaches infinity.

Setting Up the Problem

Divide the disk into \( n \) equal slices, like a pizza. Each slice has a central angle of \( \frac{2\pi}{n} \) radians (since the total angle around the center is \( 2\pi \)).

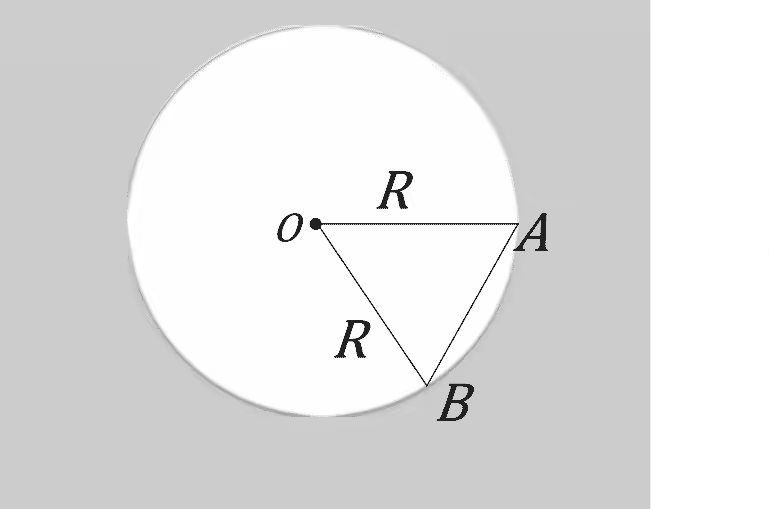

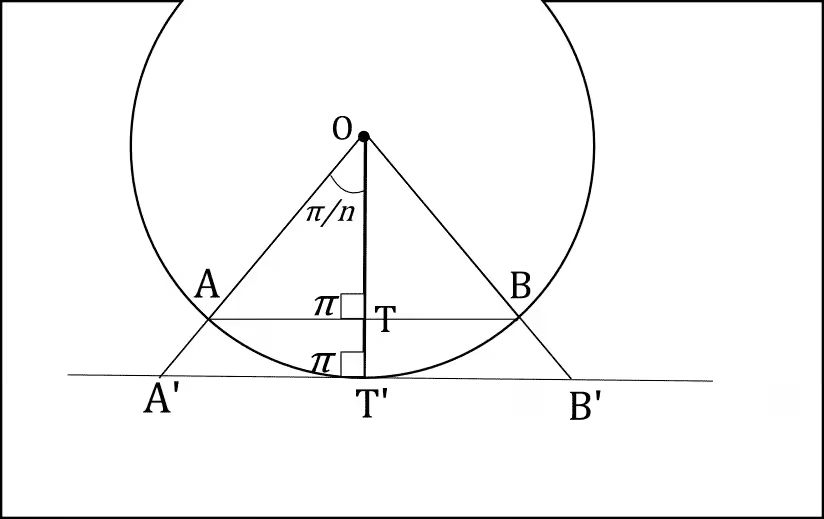

For each slice, draw a triangle by connecting the center to two adjacent points on the circumference. Call one such triangle \( \triangle OAB \), where \( O \) is the center and \( A \), \( B \) are points on the edge.

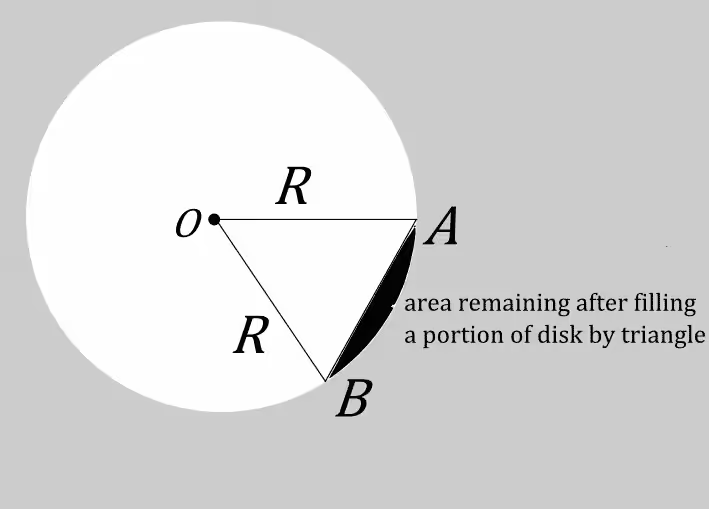

Notice something. The triangle doesn’t quite fill the slice. There’s a little curved region between the straight edge \( AB \) and the curved arc of the circle. This is the approximation error.

But here’s the key insight: as \( n \) gets larger, each triangle gets thinner, and the curved region gets smaller. In the limit as \( n \to \infty \), the triangles completely fill the disk.

The Bounding Strategy

We’ll compute two things:

- \( S_1 \) = total area of \( n \) inscribed triangles (these fit inside the disk)

- \( S_2 \) = total area of \( n \) circumscribed triangles (these contain the disk)

The true area \( A \) of the disk is sandwiched between them: \( S_1 \leq A \leq S_2 \).

If we can show that both \( S_1 \) and \( S_2 \) approach the same value as \( n \to \infty \), that value must be \( A \).

Area of an Inscribed Triangle

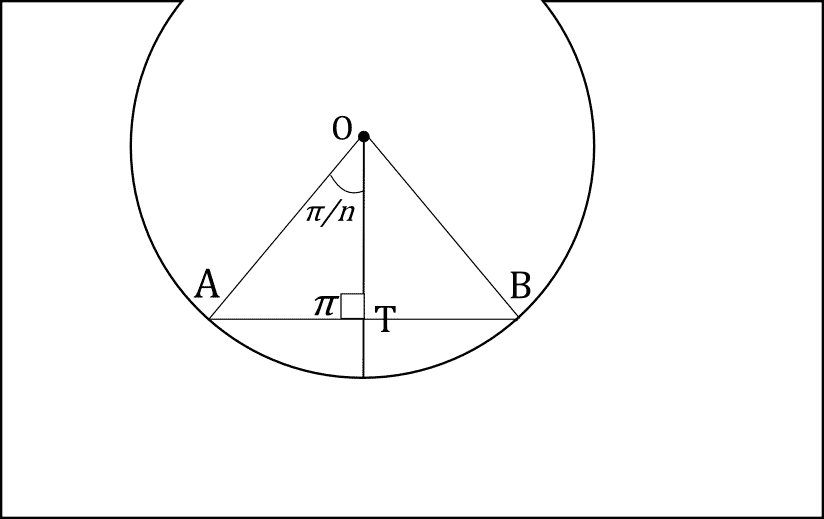

Consider triangle \( \triangle OAB \). Drop a perpendicular from \( O \) to the chord \( AB \), meeting it at point \( T \). This perpendicular bisects both the chord and the angle \( \angle AOB \).

So the triangle splits into two right triangles: \( \triangle AOT \) and \( \triangle BOT \), each with angle \( \frac{\pi}{n} \) at the center.

In right triangle \( \triangle AOT \):

- Hypotenuse \( OA = R \)

- Angle at \( O \) is \( \frac{\pi}{n} \)

- \( AT = R \sin\left(\frac{\pi}{n}\right) \)

- \( OT = R \cos\left(\frac{\pi}{n}\right) \)

Area of \( \triangle AOT \):

$$\text{Area of } \triangle AOT = \frac{1}{2} \times AT \times OT = \frac{1}{2} R \sin\left(\frac{\pi}{n}\right) \times R \cos\left(\frac{\pi}{n}\right)$$

$$= \frac{1}{2} R^2 \sin\left(\frac{\pi}{n}\right) \cos\left(\frac{\pi}{n}\right)$$

Since \( \triangle AOB \) consists of two such triangles:

$$\text{Area of } \triangle AOB = R^2 \sin\left(\frac{\pi}{n}\right) \cos\left(\frac{\pi}{n}\right)$$

With \( n \) such triangles in the disk:

$$S_1 = n R^2 \sin\left(\frac{\pi}{n}\right) \cos\left(\frac{\pi}{n}\right)$$

Area of a Circumscribed Triangle

Now extend the perpendicular \( OT \) until it hits the circumference at point \( T’ \). Draw a line through \( T’ \) perpendicular to \( OT’ \). This line is tangent to the circle and intersects the extended sides \( OA \) and \( OB \) at points \( A’ \) and \( B’ \).

Triangle \( \triangle OA’B’ \) is a circumscribed triangle. It contains the circular arc, so it overestimates the area of that slice.

In right triangle \( \triangle OA’T’ \):

- \( OT’ = R \) (it’s a radius)

- Angle at \( O \) is \( \frac{\pi}{n} \)

- \( A’T’ = R \tan\left(\frac{\pi}{n}\right) \)

Area of \( \triangle OA’T’ \):

$$\text{Area of } \triangle OA’T’ = \frac{1}{2} \times A’T’ \times OT’ = \frac{1}{2} R \tan\left(\frac{\pi}{n}\right) \times R = \frac{1}{2} R^2 \tan\left(\frac{\pi}{n}\right)$$

Since \( \triangle OA’B’ \) consists of two such triangles:

$$\text{Area of } \triangle OA’B’ = R^2 \tan\left(\frac{\pi}{n}\right)$$

With \( n \) such triangles:

$$S_2 = n R^2 \tan\left(\frac{\pi}{n}\right)$$

Taking the Limit

Now we let \( n \to \infty \) and see what happens to both bounds.

For \( S_1 \), we rewrite using the identity \( \sin\theta \cos\theta = \frac{1}{2}\sin(2\theta) \), but there’s an easier approach. Notice that:

$$S_1 = n R^2 \sin\left(\frac{\pi}{n}\right) \cos\left(\frac{\pi}{n}\right) = \pi R^2 \cdot \frac{\sin(\pi/n)}{\pi/n} \cdot \cos\left(\frac{\pi}{n}\right)$$

As \( n \to \infty \), we have \( \frac{\pi}{n} \to 0 \). And we know from calculus that:

$$\lim_{x \to 0} \frac{\sin x}{x} = 1 \quad \text{and} \quad \lim_{x \to 0} \cos x = 1$$

So:

$$\lim_{n \to \infty} S_1 = \pi R^2 \cdot 1 \cdot 1 = \pi R^2$$

For \( S_2 \):

$$S_2 = n R^2 \tan\left(\frac{\pi}{n}\right) = \pi R^2 \cdot \frac{\tan(\pi/n)}{\pi/n}$$

Since \( \lim_{x \to 0} \frac{\tan x}{x} = 1 \):

$$\lim_{n \to \infty} S_2 = \pi R^2 \cdot 1 = \pi R^2$$

The Squeeze

We have:

$$S_1 \leq A \leq S_2$$

As \( n \to \infty \):

$$\pi R^2 \leq A \leq \pi R^2$$

The only number that satisfies both inequalities is:

$$A = \pi R^2$$

And we’re done. The area of a disk is \( \pi R^2 \).

Why Two Proofs Matter

The calculus proof is faster. Three lines and you’re done.

But the method of exhaustion teaches you something deeper. It shows you how to handle infinity rigorously without calculus machinery. You trap the answer between two bounds and squeeze.

This is essentially what Archimedes did 2,300 years ago. He didn’t have limits or integrals. But he understood that you could approximate curves with polygons, and that the approximation gets perfect as you use infinitely many sides.

Calculus didn’t create these ideas. It just systematized them. When you write \( \int_0^R 2\pi x \, dx \), you’re doing what Archimedes did, but with better notation.

Where Pi Actually Comes From

Notice something interesting. Both proofs assume we know the circumference of a circle is \( 2\pi R \). But where does that come from?

This is actually the definition of \( \pi \). The number \( \pi \) is defined as the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter. So \( C = \pi \times d = \pi \times 2R = 2\pi R \).

The area formula follows from this definition. We’re not assuming two separate facts. We’re deriving one from the other.

That’s why \( \pi \) appears in both the circumference formula and the area formula. They’re connected. The area formula is a consequence of the circumference formula plus integration (or exhaustion).

Other Ways to See It

There are other beautiful proofs of \( A = \pi R^2 \).

One of my favorites: imagine cutting the disk into many thin wedges (like pizza slices) and rearranging them. Alternate the wedges point-up and point-down. With enough wedges, this shape approaches a rectangle with height \( R \) (the radius) and width \( \pi R \) (half the circumference). Area = \( R \times \pi R = \pi R^2 \).

Another approach uses the formula for the area of a sector: \( \frac{1}{2} r^2 \theta \). A full disk has angle \( 2\pi \), so area = \( \frac{1}{2} R^2 \times 2\pi = \pi R^2 \). (But this feels circular, pun intended, unless you derive the sector formula independently.)

The point is: there are many roads to \( \pi R^2 \). Each one illuminates a different aspect of why the formula works.

Why This Matters

You might think this is pure theory. It’s not.

Every time you calculate the cross-sectional area of a pipe, you use \( \pi R^2 \). Every time you figure out how much pizza you’re getting, you use \( \pi R^2 \). (A 16-inch pizza has 4 times the area of an 8-inch pizza, not twice. Think about that next time you order.)

Engineers use this formula constantly. The flow rate through a circular pipe depends on its cross-sectional area. The strength of a circular beam depends on \( \pi R^2 \). The area of a piston determines how much force an engine produces.

Understanding where formulas come from helps you remember them. And more importantly, it helps you adapt them when you encounter new problems that aren’t exactly circles.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between a disk and a circle?

A circle is just the boundary, the curved line forming the edge. A disk is the entire filled-in region including the interior. The circle is one-dimensional (a curve). The disk is two-dimensional (a surface). When people say “area of a circle,” they technically mean area of a disk.

Why is the area of a circle πR² and not 2πR?

The formula 2πR gives the circumference (perimeter), not the area. Area measures how much surface a shape covers, measured in square units. Circumference measures the length around the edge, in linear units. They’re different quantities with different formulas and different units.

What is the method of exhaustion?

The method of exhaustion is an ancient technique for finding areas of curved shapes. You approximate the shape with polygons from inside (underestimates) and outside (overestimates). As the polygons get more sides, both approximations converge to the true area. Archimedes used this to find π and areas of circles around 250 BC.

How did Archimedes calculate the area of a circle?

Archimedes inscribed and circumscribed regular polygons around a circle, calculated their areas, and showed that as the number of sides increased, both areas approached the same value. Using 96-sided polygons, he proved that π is between 3 + 10/71 and 3 + 1/7. This method predated calculus by about 1,900 years.

Why does π appear in the area formula?

π is defined as the ratio of circumference to diameter. The area formula πR² is derived from this definition through integration or exhaustion. When you add up infinitely many thin rings of circumference 2πx, π naturally appears in the result. It’s not a coincidence; area and circumference are mathematically connected.

How do you derive the area using calculus?

Slice the disk into thin concentric rings. A ring at radius x with thickness dx has area approximately 2πx dx (circumference times width). Integrate from 0 to R: ∫₀ᴿ 2πx dx = πx² evaluated from 0 to R = πR². This is one of the cleanest applications of integration.

What does the floor function have to do with the area of a circle?

Nothing directly. The floor function (greatest integer function) appears in some related problems, like counting lattice points inside a circle. But the area formula πR² itself doesn’t involve the floor function. It’s a continuous formula derived from continuous mathematics.

What is the area if I only know the diameter?

If the diameter is D, then the radius is R = D/2. Substitute into the area formula: A = π(D/2)² = πD²/4. So the area in terms of diameter is πD²/4, which is about 0.785D². A circle’s area is roughly 78.5% of the square that contains it.

Why does doubling the radius quadruple the area?

Because area depends on R². If you double R, you get (2R)² = 4R², so the area multiplies by 4. This is why a 16-inch pizza has 4 times the area of an 8-inch pizza, not twice. Area scales with the square of linear dimensions. This applies to all shapes, not just circles.

What is the relationship between area and circumference?

Area A = πR² and Circumference C = 2πR. You can express each in terms of the other: A = C²/(4π) or C = 2√(πA). There’s also a beautiful relationship: A = ½CR, meaning the area equals half the circumference times the radius. This follows directly from the integration approach.

That’s fascinating. If nature is mathematical, why didn’t I think a disc would be also.