Complete Elementary Analysis of Ramanujan’s Nested radicals

I wrote this project in 2010. I was 17 years old, studying mathematics sponsored by the INSPIRE-SHE scholarship program, and completely obsessed with a dead Indian mathematician who’d changed the world from a small town in Tamil Nadu.

Fifteen years later, I still think about nested radicals. Not because they’re practically useful (they’re not). But because they represent something rare in mathematics: patterns so beautiful they feel like they shouldn’t exist. And Ramanujan found them without computers, without formal training, without any of the tools we take for granted today.

I’ve updated and expanded my original college project into a proper mathematical monograph. You can download it below. But first, let me show you why these strange expressions with square roots inside square roots inside square roots still matter.

What Are Nested Radicals?

A nested radical is exactly what it sounds like. Square roots inside square roots. Like this:

$$\sqrt{1 + \sqrt{2 + \sqrt{3 + \sqrt{4 + \sqrt{\cdots}}}}}$$

That’s an infinite expression. The radicals go on forever. And somehow, despite looking completely untameable, many of these expressions converge to exact values.

The simplest example is this one:

$$\sqrt{1 + \sqrt{1 + \sqrt{1 + \sqrt{1 + \cdots}}}}$$

Every number under every radical is 1. Infinite nesting. What does it equal?

The golden ratio. Exactly \( \frac{1 + \sqrt{5}}{2} \), which is approximately 1.618.

That’s not an approximation. It’s not “close to” the golden ratio. It equals the golden ratio. Precisely. An infinite tower of square roots collapsing into one of the most famous numbers in mathematics.

When I first saw this in 2009, I spent an entire weekend trying to understand why it worked.

Ramanujan’s Discovery

Srinivasa Ramanujan didn’t invent nested radicals. They’d been around since Viète used them in 1593 to calculate pi. But Ramanujan did something nobody else had done: he systematized them.

He found a general formula. Given any three numbers \( x \), \( n \), and \( a \), he could generate an infinite nested radical that equals \( x + n + a \).

The formula looks intimidating at first glance. But the derivation is surprisingly elementary. It starts with the binomial theorem, the same \( (a+b)^2 = a^2 + 2ab + b^2 \) you learned in school. Through clever substitution and pattern recognition, Ramanujan built a telescoping structure that generates these infinite radicals.

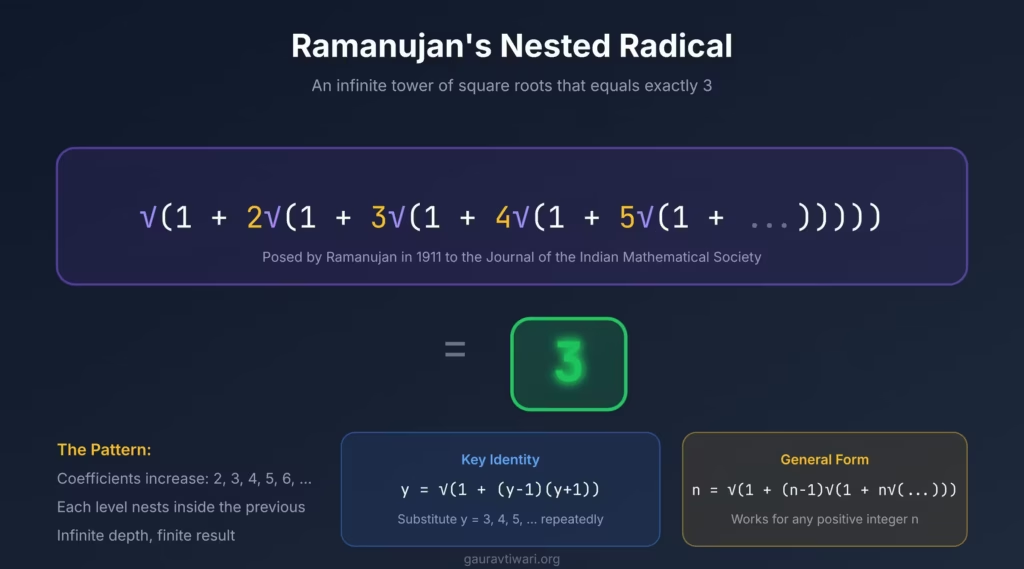

The most famous result? Set \( x = n = a = 1 \):

$$3 = \sqrt{1 + 2\sqrt{1 + 3\sqrt{1 + 4\sqrt{1 + 5\sqrt{\cdots}}}}}$$

Read that again. The number 3, an integer, equals an infinite nested radical where the coefficients are 1, 2, 3, 4, 5… going on forever. The pattern is so clean it almost feels like a trick. It’s not.

Why This Matters (And Why It Doesn’t)

I’ll be honest with you. Nested radicals have almost no practical application. You won’t use them to optimize your WordPress site. They won’t help you calculate CAC payback periods or improve your Core Web Vitals.

But that’s not the point.

Mathematics isn’t just about utility. Some of it exists because it’s beautiful. Because it reveals structure in places you didn’t expect to find it. Because it shows that simple rules, applied recursively, can generate infinite complexity that somehow resolves into elegant simplicity.

Ramanujan worked on nested radicals before he turned 20. He was self-taught, working from a single outdated textbook in colonial India. He had no mentor, no internet, no computer algebra system. Just paper, pencil, and an intuition for patterns that still baffles mathematicians today.

That’s what drew me to this topic in 2010. And it’s why I decided to revisit it now.

The Connection to Continued Fractions

Here’s something that surprised me when I was researching this project: nested radicals and continued fractions are secretly the same thing.

A continued fraction looks like this:

$$1 + \cfrac{1}{1 + \cfrac{1}{1 + \cfrac{1}{1 + \cdots}}}$$

Different structure. Same result. This also equals the golden ratio.

The general relationship is:

$$\sqrt{a + b\sqrt{a + b\sqrt{a + \cdots}}} = a + \cfrac{b}{a + \cfrac{b}{a + \cfrac{b}{\ddots}}}$$

Both equal \( \frac{a + \sqrt{a^2 + 4b}}{2} \).

Two completely different infinite structures converging to the same value. When I first proved this in my college project, I felt like I’d discovered a secret passage between two rooms I thought were separate. That feeling, more than any grade or scholarship, is why I studied mathematics.

Ramanujan’s Wild Theorem

In January 1913, Ramanujan sent a letter to G.H. Hardy at Cambridge. The letter contained dozens of formulas, many without proof. Hardy later said some of them “defeated me completely.”

One of them was this:

$$\cfrac{1}{1 + \cfrac{e^{-2\pi}}{1 + \cfrac{e^{-4\pi}}{1 + \cfrac{e^{-6\pi}}{1 + \ddots}}}} = \left(\sqrt{\frac{5 + \sqrt{5}}{2}} – \frac{\sqrt{5} + 1}{2}\right)\sqrt[5]{e^{2\pi}}$$

Look at the left side. An infinite continued fraction with exponential terms. Look at the right side. Fifth roots, the golden ratio, and \( e^{2\pi} \). Completely different mathematical objects. And they’re equal.

Hardy eventually verified it was true. But he never fully understood how Ramanujan found it.

This is what I mean when I say Ramanujan saw patterns others couldn’t. He wasn’t just good at calculation. He had an almost supernatural ability to recognize when two things that looked different were secretly connected.

What I Changed in the Updated Monograph

My original 2010 project was rough. The LaTeX was messy, the proofs were incomplete, and I made some errors in the calculus section. I was 17 and learning as I went.

For the 2026 update, I:

- Rewrote all proofs with proper theorem/proof structure

- Added Herschfeld’s convergence theorem (1935), which I didn’t know about in 2010

- Expanded the section on continued fraction duality

- Fixed the integration errors in the calculus chapter

- Added Viète’s 1593 formula connecting nested radicals to pi

- Included numerical values and the plastic constant

- Typeset the whole thing properly with STIX Two fonts

The result is an 18-page monograph that covers nested radicals from basic definitions through convergence theory to differential calculus. It’s still elementary (no modular forms or q-series), but it’s rigorous.

The Golden Ratio Keeps Showing Up

One thing that still amazes me: the golden ratio \( \varphi = \frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2} \) appears everywhere in nested radical theory.

It’s the simplest infinite nested radical:

$$\varphi = \sqrt{1 + \sqrt{1 + \sqrt{1 + \cdots}}}$$

It’s the simplest infinite continued fraction:

$$\varphi = 1 + \cfrac{1}{1 + \cfrac{1}{1 + \cfrac{1}{\ddots}}}$$

It satisfies the equation \( \varphi^2 = \varphi + 1 \), which is exactly the functional equation that defines convergence for these structures.

And it shows up in Ramanujan’s wild theorem, hiding inside that mess of exponentials and fifth roots.

The golden ratio isn’t special because ancient Greeks liked it or because it appears in sunflowers. It’s special because it’s the fixed point of some of the simplest recursive structures in mathematics. Nested radicals reveal this in a way that other approaches don’t.

Unsolved Problems

Not everything about nested radicals is understood. Here’s a question nobody has answered:

$$\sqrt{1 + \sqrt{2 + \sqrt{3 + \sqrt{4 + \cdots}}}} = \text{?}$$

We know it converges. Herschfeld’s theorem guarantees that. We can compute it to arbitrary precision: approximately 1.7579327566…

But is it algebraic or transcendental? Does it have a closed form? Nobody knows.

I find this oddly comforting. Even in elementary mathematics, there are mysteries left. Problems simple enough to state to a high school student, but hard enough that no one has solved them.

Download the Full Monograph

I’ve made the complete PDF available for download. It’s 18 pages of properly typeset mathematics covering:

- Definitions and denesting algorithms

- Ramanujan’s general formula with full derivation

- Convergence theory (Herschfeld’s theorem)

- Continued fraction duality

- The wild theorem

- Calculus of nested radicals (differentiation and integration)

- Open problems and further directions

The LaTeX source is also available if you want to modify it or use it as a template for your own mathematical writing.

The Calculus of Nested Radicals

One section of the monograph that I’m particularly proud of is the calculus chapter. It wasn’t in my original 2010 project (I hadn’t taken real analysis yet), and I added it for this update.

Here’s the setup. Define a sequence of functions:

$$f_1(x) = \sqrt{x + k}$$

$$f_2(x) = \sqrt{x + \sqrt{x + k}}$$

$$f_3(x) = \sqrt{x + \sqrt{x + \sqrt{x + k}}}$$

Each function has one more level of nesting. The question: are these differentiable? Integrable? What patterns emerge?

The derivatives form their own nested structure. For \( f_1 \), it’s straightforward: \( f_1′(x) = \frac{1}{2\sqrt{x+k}} \).

For \( f_2 \), you need the chain rule:

$$f_2′(x) = \frac{1}{2f_2(x)}\left(1 + \frac{1}{2f_1(x)}\right)$$

The pattern continues. Each derivative depends on all the previous functions. It’s recursion all the way down.

Integration is messier. \( \int f_1(x) \, dx \) has a closed form. \( \int f_2(x) \, dx \) involves logarithms. By \( f_3 \), you’re unlikely to find an elementary antiderivative at all.

This is typical in mathematics. Differentiation is mechanical. Integration is an art. And nested radicals make that contrast especially vivid.

A Note on Mathematical Beauty

I’ve spent most of my career writing about practical things. WordPress performance. SEO strategies. Business metrics. Content that helps people solve concrete problems.

But I started as a mathematician. And mathematicians have a different relationship with their work.

When I first proved that nested radicals and continued fractions converge to the same values, I wasn’t thinking about applications. I was thinking about structure. About the fact that two seemingly unrelated infinite processes produce identical results. About what that says about the nature of numbers themselves.

There’s a reason Ramanujan said his equations expressed “thoughts of God.” Not because he was religious in any conventional sense, but because mathematical truth feels discovered rather than invented. These patterns existed before humans. They’ll exist after we’re gone. We’re just fortunate enough to glimpse them occasionally.

That might sound grandiose for a blog post about square roots. But if you’ve ever felt the click of a proof coming together, you know what I mean. It’s not satisfaction. It’s recognition. Like remembering something you somehow already knew.

Why I’m Sharing This Now

I started gauravtiwari.org as a math blog in 2008. Then it evolved into WordPress tutorials, then business content, then whatever it is now. But mathematics was the original love.

Every few years, I remember that. I dig up old projects, old notebooks, old fascinations. And I’m reminded that before I cared about page speed or conversion rates, I cared about why \( 1 + 1 + 1 + \cdots \) under infinite square roots equals exactly 3.

This project represents something important to me. It’s proof that the 17-year-old version of myself was onto something. That mathematical beauty isn’t frivolous. That taking time to understand things deeply, even things with no practical application, makes you a better thinker.

If you’re a student working on your own mathematical interests, don’t let anyone tell you it’s a waste of time. The discipline of proving things rigorously, of following patterns to their logical conclusions, of sitting with confusion until clarity emerges… those skills transfer to everything else you’ll ever do.

I built a business on WordPress and content marketing. But I learned how to think by studying nested radicals.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a nested radical in simple terms?

A nested radical is a mathematical expression where square roots contain other square roots. Think of it like Russian nesting dolls, but with square root symbols. The simplest example is √(1 + √(1 + √(1 + …))) which equals the golden ratio, approximately 1.618.

Why is Ramanujan famous for nested radicals?

While nested radicals existed before Ramanujan, he was the first to find general formulas for generating them. He discovered that any sum x + n + a can be expressed as an infinite nested radical following a specific pattern. This systematization was unprecedented and revealed deep connections to continued fractions.

What is the golden ratio’s connection to nested radicals?

The golden ratio (φ ≈ 1.618) equals both the simplest infinite nested radical √(1 + √(1 + √(1 + …))) and the simplest continued fraction 1 + 1/(1 + 1/(1 + …)). It’s the unique positive number satisfying φ² = φ + 1, which is the convergence equation for constant-coefficient nested radicals.

Do nested radicals have practical applications?

Honestly, not many. They appear in some computer graphics algorithms and numerical analysis, but they’re not widely used in engineering or applied mathematics. Their value is primarily theoretical and aesthetic. They reveal deep structural connections in mathematics and train rigorous thinking skills.

How do you prove that √(2 + √(2 + √(2 + …))) equals 2?

Let L equal the infinite nested radical. Then L = √(2 + L) by the self-similar structure. Squaring both sides gives L² = 2 + L, or L² – L – 2 = 0. Factoring: (L-2)(L+1) = 0. Since L must be positive, L = 2. This technique works for any constant-coefficient nested radical.

Where can I learn more about Ramanujan’s mathematics?

Start with Bruce Berndt’s five-volume series ‘Ramanujan’s Notebooks’ for rigorous coverage. For accessible introductions, try Robert Kanigel’s biography ‘The Man Who Knew Infinity’ or G.H. Hardy’s ‘Ramanujan: Twelve Lectures.’ My monograph covers nested radicals specifically at an undergraduate level.