Lipid

Lipids are a broad class of biological molecules made up of carbon, hydrogen, and a relatively small amount of oxygen. Unlike carbohydrates and proteins, lipids are insoluble in water but dissolve readily in organic solvents such as benzene, acetone, and ether. You won’t find lipids forming true polymers the way proteins or nucleic acids do. Instead, they are assembled from smaller molecular building blocks through dehydration reactions.

What makes lipids fascinating is their sheer versatility. A lipid molecule might be as simple as a single fatty acid chain or as complex as a steroid with four fused carbon rings. Some lipids store enormous amounts of energy, others form the structural backbone of every cell membrane in your body, and a few even act as chemical messengers between cells. Understanding lipids is essential because they touch nearly every aspect of biology, from nutrition and metabolism to disease and drug design.

Classification of Lipids

Scientists classify lipids into three major groups based on their chemical composition and structure: simple lipids, compound (conjugated) lipids, and derived lipids. This classification helps you understand both how these molecules are built and what roles they play inside living organisms.

Simple Lipids

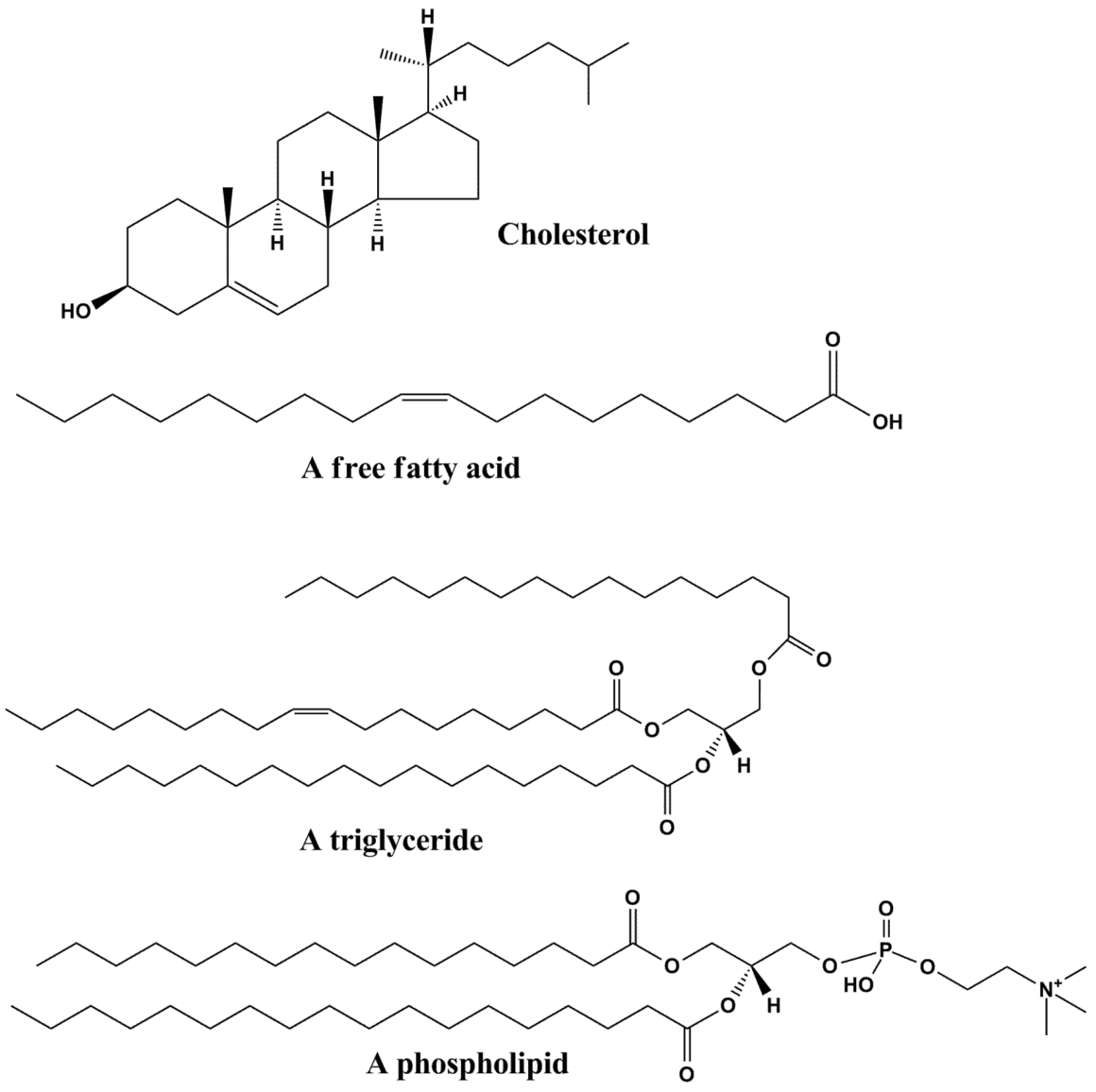

Simple lipids are esters of fatty acids with various alcohols. They contain only carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms, with no additional chemical groups attached. You can think of them as the most straightforward lipid molecules. They fall into two main categories: neutral (true) fats and waxes.

Neutral or true fats

Neutral fats are also called glycerides. Every fat molecule is an ester formed from one molecule of glycerol and one to three molecules of the same or different long-chain fatty acids. Glycerol is chemically trihydroxypropane, a small three-carbon molecule with three hydroxyl (-OH) groups. A fatty acid, on the other hand, is an unbranched chain of carbon atoms with a carboxylic group (-COOH) at one end and an R group at the other.

The R group could be a methyl (-CH3) group, an ethyl (-C2H5) group, or a longer chain with a higher number of -CH2 groups (ranging from one carbon to 19 carbons). For example, palmitic acid (C16H32O2) has 16 carbon atoms including the carboxyl carbon. Arachidonic acid possesses 20 carbon atoms including the carboxyl carbon. The length and saturation of these carbon chains determine many of the physical and chemical properties you observe in different fats.

Fatty acids come in two types:

- Saturated fatty acids like palmitic acid and stearic acid contain no double bonds between their carbon atoms. Their chains pack tightly together, which is why saturated fats tend to be solid at room temperature.

- Unsaturated fatty acids such as oleic, linoleic, linolenic, and arachidonic acids possess one or more double bonds. These double bonds introduce kinks in the carbon chain, preventing tight packing and keeping unsaturated fats liquid at room temperature.

Doctors often recommend oils containing polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), meaning fatty acids with more than one double bond, to people with hypertension, high blood cholesterol, and other cardiovascular diseases. Research has consistently shown that PUFAs help lower blood cholesterol levels. Sunflower oil and safflower oil are particularly rich sources of polyunsaturated fatty acids.

Depending on the number of fatty acid molecules attached to a molecule of glycerol, neutral fats may be monoglycerides (one fatty acid), diglycerides (two fatty acids), or triglycerides (three fatty acids). Triglycerides are the most common form of stored fat in your body and serve as a concentrated energy reserve.

Based on their melting point, triglycerides can be classified as fats or oils. Fats (such as butter and ghee) have high melting points and remain solid at room temperature. Oils (such as sunflower oil and groundnut oil) have lower melting points and remain liquid at room temperature. This difference comes down to chain length and saturation: shorter chains and more double bonds mean lower melting points.

Waxes

Waxes are esters of fatty acids with long-chain alcohols of higher molecular weight (not glycerol). They tend to be much harder and more resistant to hydrolysis than ordinary fats. In nature, waxes play a critical protective role. They form water-insoluble coatings on the skin and hair of animals and on the stems, fruits, and leaves of plants. If you’ve ever noticed the waxy sheen on an apple or the water-repellent quality of bird feathers, you’re looking at waxes in action.

Beeswax is chemically hexacosyl palmitate, formed from palmitic acid and myricyl alcohol. Worker bees secrete it from their abdominal glands to build honeycomb structures. Lanolin, also known as wool fat, forms a waterproof coating around animal furs and is widely used in cosmetics and skincare products. Carnauba wax, obtained from the leaves of the Brazilian palm tree, is one of the hardest natural waxes and is used in car polishes and floor waxes. On the pathogenic side, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium leprae produce a harmful wax known as wax-D that contributes significantly to their ability to cause disease.

Compound or Conjugated Lipids

Compound lipids are esters of fatty acids with alcohols that also contain additional chemical groups such as phosphate, sugar residues, or proteins. These extra components give compound lipids unique properties that simple lipids lack, particularly when it comes to membrane structure and cell signaling. You’ll encounter four important subgroups here.

Phospholipids

Phospholipids are arguably the most important structural lipids in your body. Each phospholipid molecule is built on a glycerol backbone with:

- A phosphate group joined to one of its outer -OH groups

- Two fatty acid molecules linked to the other two -OH groups

- A nitrogen-containing compound (such as choline) bound to the phosphate group

This structure gives phospholipids a distinctive dual character. The phosphate head is hydrophilic (water-loving), while the two fatty acid tails are hydrophobic (water-fearing). When placed in water, phospholipids spontaneously arrange themselves into a bilayer, with the hydrophilic heads facing outward and the hydrophobic tails tucked inside. This is exactly how cell membranes are formed. Lecithin and cephalin are common examples of phospholipids found in biological membranes throughout the body.

Glycolipids

Glycolipids contain fatty acids, the amino alcohol sphingosine, and a sugar residue (usually galactose). In their structure, one of the fatty acid positions is replaced by the sugar molecule. You can think of glycolipids as lipids with a sugar tag that helps cells recognize and communicate with each other.

Glycolipids are particularly abundant in the myelin sheath, the insulating layer that wraps around nerve fibers and allows electrical impulses to travel quickly along neurons. They are also found in the outer leaflet of the cell membrane, where they play a key role in cell-to-cell recognition and immune response. Cerebrosides and gangliosides are two well-known categories of glycolipids. Gangliosides, found in high concentrations in brain tissue, are involved in signal transduction and neuronal development.

Lipoproteins

Lipoproteins are molecular complexes that combine lipids (mostly phospholipids and cholesterol) with proteins. Since lipids are hydrophobic and cannot travel freely in the blood, lipoproteins act as transport vehicles that carry lipids through the aqueous environment of your bloodstream.

You’ve likely heard of the major types in a medical context: LDL (low-density lipoprotein), often called “bad cholesterol” because it deposits cholesterol in artery walls, and HDL (high-density lipoprotein), known as “good cholesterol” because it helps remove excess cholesterol from tissues and transport it back to the liver. Lipoproteins are also essential structural components of cellular membranes and mitochondrial membranes.

Chromolipids

Chromolipids are lipids that contain colored pigments, most notably carotenoids. Carotenoids include carotene, xanthophyll, and the precursors to vitamin A. The vivid yellow, orange, and red colors you see in carrots, tomatoes, autumn leaves, and flamingo feathers are all due to carotenoid pigments. Beyond color, these pigments serve vital biological functions: carotene is converted into vitamin A (retinol) in your body, which is essential for vision, immune function, and skin health.

Derived Lipids

Derived lipids are molecules that do not fit neatly into the simple or compound categories but are classified as lipids because they share key fat-like properties, particularly their insolubility in water. The most important derived lipids you should know are steroids, prostaglandins, and terpenes.

Steroids

Although steroids don’t contain fatty acid residues, they are considered lipids because of their hydrophobic nature. Instead of having a straight carbon chain, steroids possess a characteristic structure of four fused carbon rings (three six-membered rings and one five-membered ring). Different steroids differ from each other in the number and position of double bonds and in the side groups attached to the rings.

Sterols are the most common steroids found in nature. Cholesterol is the most abundant sterol in animal tissues and is found in foods containing animal fats such as egg yolks, meat, and dairy products. Your liver synthesizes cholesterol, and it serves as an essential component of animal cell membranes, where it regulates membrane fluidity. Cholesterol also acts as a precursor for the synthesis of steroid hormones (estrogen, testosterone, cortisol), vitamin D, and bile acids. Ergosterol plays a similar role in fungal cell membranes, while phytosterols are found in plant cells.

Diosgenin is a steroidal compound found in yams that is used as a starting material in the commercial manufacture of anti-fertility pills and other steroid-based medications.

Prostaglandins

Prostaglandins are a category of hormone-like unsaturated fatty acids that act as local messenger molecules between cells. They are derived from arachidonic acid and other similar C20 fatty acids. Unlike hormones that travel through the bloodstream to distant target organs, prostaglandins typically act on cells near their site of synthesis.

Prostaglandins play roles in inflammation, pain perception, fever regulation, blood clotting, and smooth muscle contraction. When you take aspirin or ibuprofen to reduce pain or inflammation, these drugs work by inhibiting the enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX), which is required for prostaglandin synthesis. This is why understanding prostaglandins matters beyond the biology classroom; it directly connects to how common medications work in your body.

Functions of Lipids

Lipids perform a remarkably wide range of functions in living organisms. Here are the key roles you should remember:

- Energy storage: Gram for gram, fats yield more than twice the energy of carbohydrates (about 9 kcal per gram versus 4 kcal per gram). This makes triglycerides the most efficient form of long-term energy storage in your body.

- Structural role: Phospholipids and cholesterol are the primary building blocks of all biological membranes. Without them, cells simply could not maintain their internal environment.

- Insulation and protection: Subcutaneous fat (adipose tissue) insulates your body against heat loss and cushions vital organs like the kidneys and heart against mechanical shock.

- Waterproofing: Waxes provide a water-resistant barrier on plant leaves, animal fur, bird feathers, and insect exoskeletons.

- Signaling: Steroid hormones, prostaglandins, and other lipid-derived molecules act as chemical signals that regulate metabolism, reproduction, immunity, and inflammation.

- Vitamin absorption: Fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) require lipids for absorption from the digestive tract. A diet completely devoid of fat would lead to deficiencies in these critical vitamins.

What are lipids and their primary functions in the body?

Lipids are a diverse group of hydrophobic organic molecules, including fats, oils, and steroids, that serve essential functions such as energy storage, cellular structure, and signaling.

How do lipids differ from carbohydrates and proteins?

Lipids are primarily non-polar and hydrophobic, while carbohydrates and proteins are polar and hydrophilic, contributing to their distinct roles in metabolism and cell structure.

What types of lipids are commonly found in biological systems?

Common types of lipids include triglycerides, phospholipids, sterols, and waxes, each serving unique structural and functional roles in cells.

What is the role of phospholipids in cell membranes?

Phospholipids form the bilayer structure of cell membranes, providing a barrier to protect cellular components while allowing selective permeability for molecules.

How do unsaturated and saturated fatty acids impact health?

Unsaturated fatty acids can improve heart health by lowering bad cholesterol levels, while saturated fatty acids, in excess, may increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases.

What are essential fatty acids, and why are they important?

Essential fatty acids, such as omega-3 and omega-6, cannot be synthesized by the body and must be obtained through diet, playing crucial roles in inflammation regulation and brain function.

How are lipids metabolized in the body?

Lipids are metabolized through processes such as lipolysis and beta-oxidation, where they are broken down into fatty acids and glycerol for energy production and other metabolic functions.

I teach introductory biology and often point my students to this resource. The explanations are accurate and accessible.

The real-world examples make lipids so much more interesting. I actually enjoyed studying this chapter now.

The FAQs at the end are really useful. They cover the exact questions students typically ask about lipids.

I’m studying for my biology exam and this article saved me. Everything about lipids is covered so clearly.

The real-world examples make lipids so much more interesting. I actually enjoyed studying this chapter now.

I’m studying for my biology exam and this article saved me. Everything about lipids is covered so clearly.

I love how you connect the structure of lipids to its biological function. That’s the key insight most resources miss.

This is an excellent overview of lipids. The level of detail is perfect for undergraduate students.

Shared this with my entire study group. The phospholipids and cell membranes section in particular cleared up a lot of confusion.

This page on lipids is now my primary reference for revision. Well-written, accurate, and free. Can’t ask for more.

Your explanation of phospholipids and cell membranes is the clearest I’ve seen anywhere. I finally understand how it all fits together.

As a medical student, understanding lipids at the molecular level is crucial. This resource nails that balance between depth and clarity.