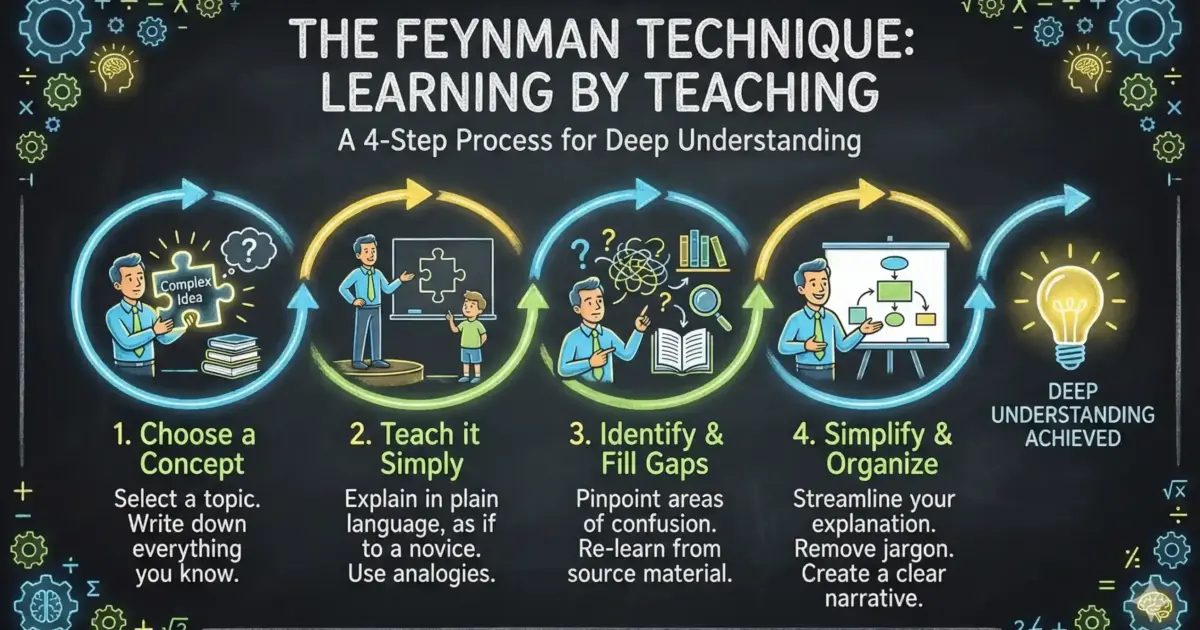

The Feynman Technique: Learning by Teaching

Richard Feynman won a Nobel Prize in physics. He could explain quantum electrodynamics to other physicists – not a big deal. But what made him remarkable was his ability to explain complex ideas so simply that non-experts could understand them. He believed that if you couldn’t explain something simply, you didn’t really understand it. This belief became the foundation of what we now call the Feynman Technique.

I’ve used this technique to learn everything from financial modeling to programming languages. It’s deceptively simple. And it works because it exposes the gaps in your understanding that passive reading or listening can’t reveal.

Here’s how it works and why it’s one of the most effective learning method I’ve found.

The Four Steps

The Feynman Technique has four steps. Each one matters, and skipping any of them reduces the technique’s power.

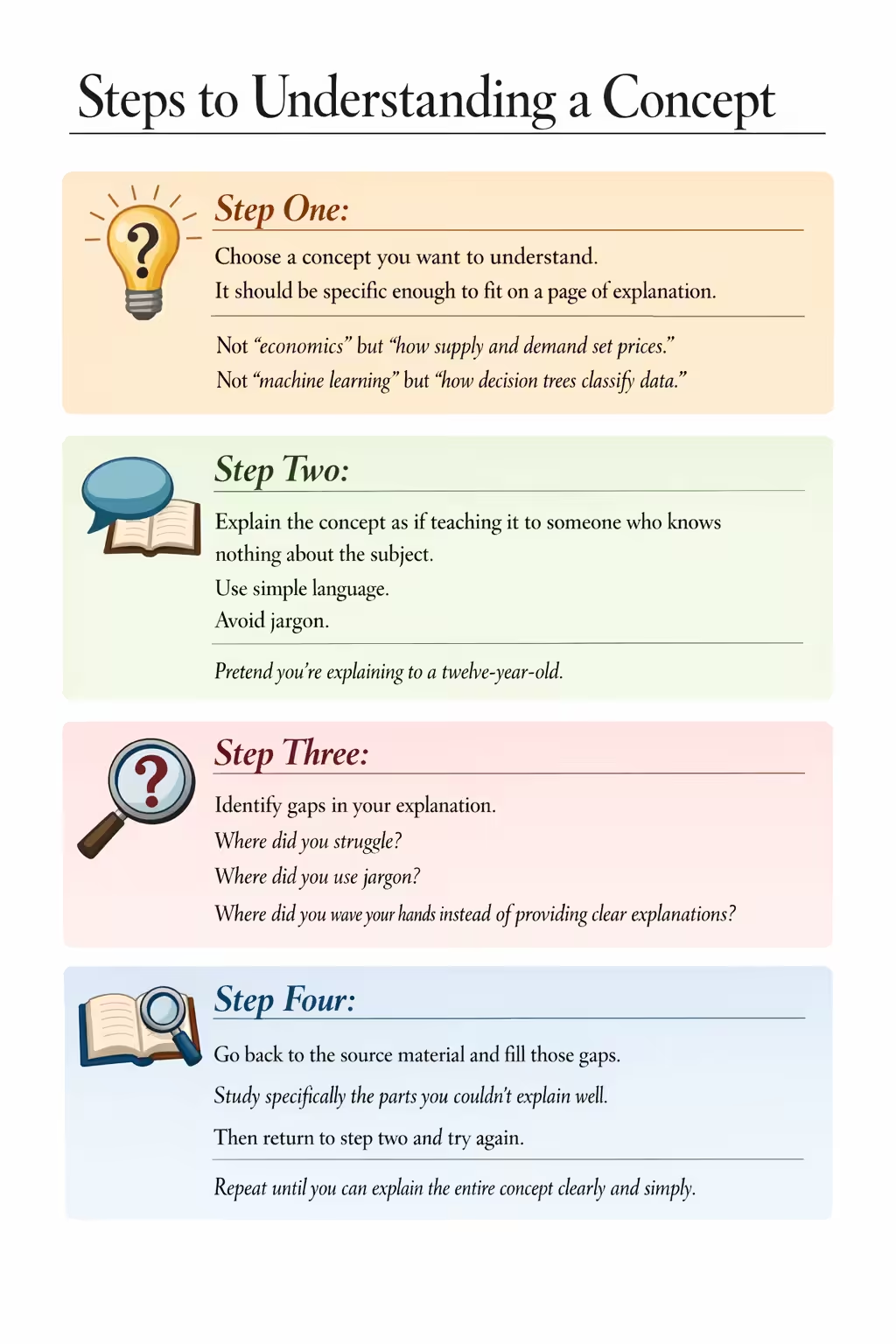

- Step one: Choose a concept you want to understand. It should be specific enough to fit on a page of explanation. Not “economics” but “how supply and demand set prices.” Not “machine learning” but “how decision trees classify data.”

- Step two: Explain the concept as if teaching it to someone who knows nothing about the subject. Write it out or say it out loud. Use simple language. Avoid jargon. Pretend you’re explaining to a twelve-year-old or to someone with no background in the field.

- Step three: Identify gaps in your explanation. Where did you struggle? Where did you use jargon because you couldn’t find simpler words? Where did you wave your hands instead of providing clear explanations? These gaps are exactly where your understanding is weak.

- Step four: Go back to the source material and fill those gaps. Study specifically the parts you couldn’t explain well. Then return to step two and try again. Repeat until you can explain the entire concept clearly and simply.

That’s it. Four steps. But executing them honestly reveals just how little we often understand things we think we know.

Why Teaching Forces Understanding

Reading about something isn’t the same as understanding it. I’ve read dozens of articles about how blockchain works. I could parrot phrases like “distributed ledger” and “consensus mechanism.” But when I tried to explain it simply, I realized I couldn’t answer basic questions. What problem does it actually solve? Why can’t you just use a regular database? My surface knowledge crumbled under the demand for actual explanation.

Teaching forces you to organize ideas in logical sequence. You can’t just recognize concepts when they appear. You have to structure them into a coherent narrative. This structuring is where understanding happens. Disconnected facts become connected knowledge.

Teaching also forces you to address why, not just what. Passive learning often captures the what: this term means that, this formula calculates that. But teaching demands causation and connection. Why does it work this way? What happens if this part is different? What comes before and after?

The Feynman Technique leverages a psychological truth: we’re excellent at fooling ourselves into thinking we understand. Reading feels like learning. Recognizing feels like knowing. The act of teaching removes the crutch of recognition and demands production. Can you generate the explanation, not just recognize it when someone else explains? This is why active recall is so effective.

Finding the Gaps

The most valuable part of the Feynman Technique is step three: identifying gaps. This is where real learning begins.

- Gaps appear in several ways. You might use jargon because you don’t understand well enough to translate it. If you explain “regression to the mean” as “things tend to regress to the mean,” you haven’t explained anything. You need to describe it in terms anyone could understand.

- Gaps appear when you skip steps. “And then you just…” means you’re glossing over something you don’t fully understand. Every “just” in an explanation deserves scrutiny.

- Gaps appear when you can’t answer follow-up questions. If someone asks “but why?” and you don’t have an answer, that’s a gap. Real understanding includes the why behind the what.

- Gaps appear when analogies break down. Analogies are powerful teaching tools, but when you can’t explain where the analogy stops being accurate, you’ve found the edge of your understanding.

Be ruthlessly honest during this step. The technique only works if you acknowledge when your explanation is inadequate. The natural tendency is to convince yourself your explanation was good enough. It rarely is on the first attempt.

Practical Application

Let me walk through applying the Feynman Technique to a concept: compound interest.

- First attempt at explanation:

- Compound interest is when you earn interest on interest. You put money in a savings account, you earn interest. That interest gets added to your balance. Next period, you earn interest on the larger balance, including the previous interest. So your money grows faster over time.

- Gap identification: That’s a surface explanation. It doesn’t explain why it matters, how to calculate it, or what factors affect it. Someone hearing that explanation couldn’t apply it to their own situation.

- Going back to source material: I research the math, the time factor, the comparison to simple interest, the real-world implications.

- Second attempt:

- Compound interest is money making money, which then makes more money. Say you have $1,000 earning 5% per year. After year one, you have $1,050. But in year two, you don’t just add another $50. You earn 5% of $1,050, which is $52.50. Now you have $1,102.50. Each year, the interest earned grows because your base is always bigger than before.

- The magic happens over time. At 5% compounding, your money doubles roughly every 14 years. After 28 years, it’s quadrupled. The curve looks flat at first but gets steep later. This is why starting to save young matters so much. Ten years of extra compounding can double your final amount.

- The factors that matter: the interest rate (higher is better), the time (longer is better), and how often interest compounds (more frequent is better). Daily compounding at 5% beats annual compounding at 5%, though the difference is small.

- Gap check: Better. I can now explain the concept and its practical implications. I could continue refining by adding more about the math, comparisons to inflation, or common mistakes people make. Each refinement deepens understanding.

Using It for Complex Subjects

The Feynman Technique scales to complex subjects by breaking them into smaller concepts.

Suppose you want to understand “machine learning.” That’s too broad for one explanation. Break it down. What is supervised learning? What is a training dataset? What is overfitting? Each of these becomes its own Feynman exercise.

As you master the smaller concepts, you build understanding of the larger subject. Start with the foundational pieces. Explain those clearly. Then explain how they connect. Then explain the next layer. Complex subjects become manageable as stacks of simple explanations.

This approach also reveals the structure of knowledge. You learn what depends on what. You understand which concepts are fundamental and which are derived. This structural understanding helps you learn related topics faster because you already have the foundation. For organizing this knowledge, consider using note-taking apps.

Beyond Individual Learning

The Feynman Technique has applications beyond personal study.

Teachers and trainers can use it to prepare lessons. If you can’t explain something simply, you’re not ready to teach it. Using the technique forces you to anticipate student confusion and address it proactively.

Teams can use it to align understanding. When a team member explains a concept and others identify gaps or ask questions, the whole team learns. Different perspectives reveal blind spots that individuals miss.

Writers can use it to create clear explanations. The process of explaining to an imaginary novice produces writing that communicates effectively to real readers.

I use a version of this when creating content. Before writing about a topic, I explain it out loud as if teaching. The gaps I find become the sections that need the most research and careful explanation.

Common Mistakes

The Feynman Technique fails when people don’t do it honestly.

The most common mistake is satisfying yourself too easily. Your first explanation feels good enough. You don’t push to find gaps. You don’t try again. But good enough isn’t the point. The point is genuine understanding, which requires multiple passes.

Another mistake is staying at the surface level. You explain what something is but not why it matters or how it connects to other concepts. True understanding includes context and implications, not just definitions.

A third mistake is not actually writing or speaking the explanation. Thinking about how you’d explain something is different from actually doing it. The act of producing language forces precision that mere thinking doesn’t require.

Finally, some people avoid the technique because it feels slow. Reading feels faster than explaining. But reading without understanding isn’t actually learning. The Feynman Technique might take longer per concept, but the understanding sticks. Time spent truly learning beats time spent giving yourself the illusion of learning.

Making It a Habit

For the Feynman Technique to transform your learning, it needs to become habitual.

After reading or listening to something you want to learn, pause and explain it. Even a quick verbal summary forces some processing. Save deep application for concepts that really matter to you.

Keep a learning journal where you write explanations of new concepts. Revisiting these explanations weeks later reveals how well you retained the material. If you can’t explain it again, you need to relearn it.

Teach others when opportunities arise. Explaining concepts to colleagues, friends, or students is the Feynman Technique in real life. Every teaching opportunity is a learning opportunity for you.

Notice when you’re using jargon without understanding. This awareness extends beyond formal study. In conversations, in reading, in work. When you catch yourself nodding along without true comprehension, that’s a signal to apply the technique.

The more you use this method, the more natural it becomes. You start instinctively testing your understanding by trying to explain things simply. And you get comfortable saying “I don’t actually understand that” because you know the fix is just a Feynman session away.

FAQs

Disclaimer: This site is reader‑supported. If you buy through some links, I may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. I only recommend tools I trust and would use myself. Your support helps keep gauravtiwari.org free and focused on real-world advice. Thanks. — Gaurav Tiwari