Fox-Rabbit Chase Problem [Solution & Math Proof]

Pursuit problems are some of the most elegant challenges in classical mechanics. Two objects moving, one chasing, the other evading. The math gets surprisingly deep.

This problem comes from David Morin’s “Introduction to Classical Mechanics,” and it’s a personal favorite. A fox chases a rabbit. Both run at the same speed. But the rabbit doesn’t run straight away. It runs at an angle. What happens?

The answer depends on that angle. And the solution involves some genuinely clever tricks.

The Problem

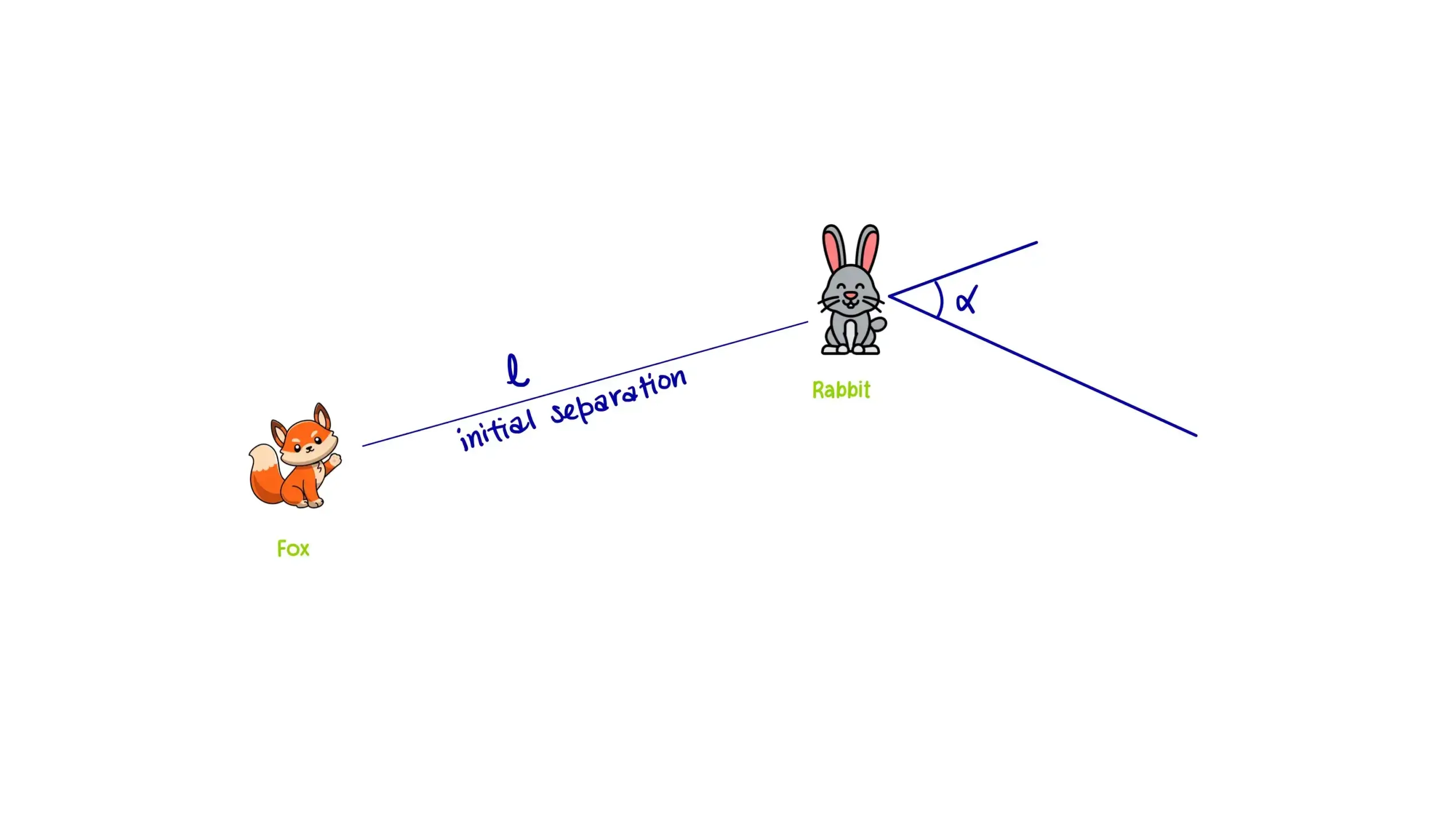

Part I: The Spiral Chase

A fox chases a rabbit. Both run at the same speed \( v \). The fox always runs directly toward where the rabbit is right now (not where it’s going). The rabbit runs at a constant angle \( \alpha \) relative to the direction directly away from the fox.

The initial separation is \( l \).

Does the fox catch the rabbit? If so, when and where? If not, what’s their final separation?

Part II: The Straight-Line Escape

Same setup, but now the rabbit runs in a fixed straight line (its initial direction from Part I). It doesn’t keep adjusting.

Same questions. Does the fox catch the rabbit? When? Where? Or what’s the eventual separation?

Try these before reading the solutions. They’re harder than they look.

Solution: Part I

The fox always closes the gap. The rabbit always partially reopens it by not running straight away.

The relative speed along the line connecting them is \( v – v\cos\alpha \). The fox gains ground at this rate. So the time to close the initial gap \( l \) is:

$$T = \frac{l}{v(1 – \cos\alpha)}$$

This works unless \( \alpha = 0 \). If the rabbit runs directly away, neither gains ground. The fox never catches up.

Finding where they meet is trickier. I’ll show you two approaches.

The Elegant Method

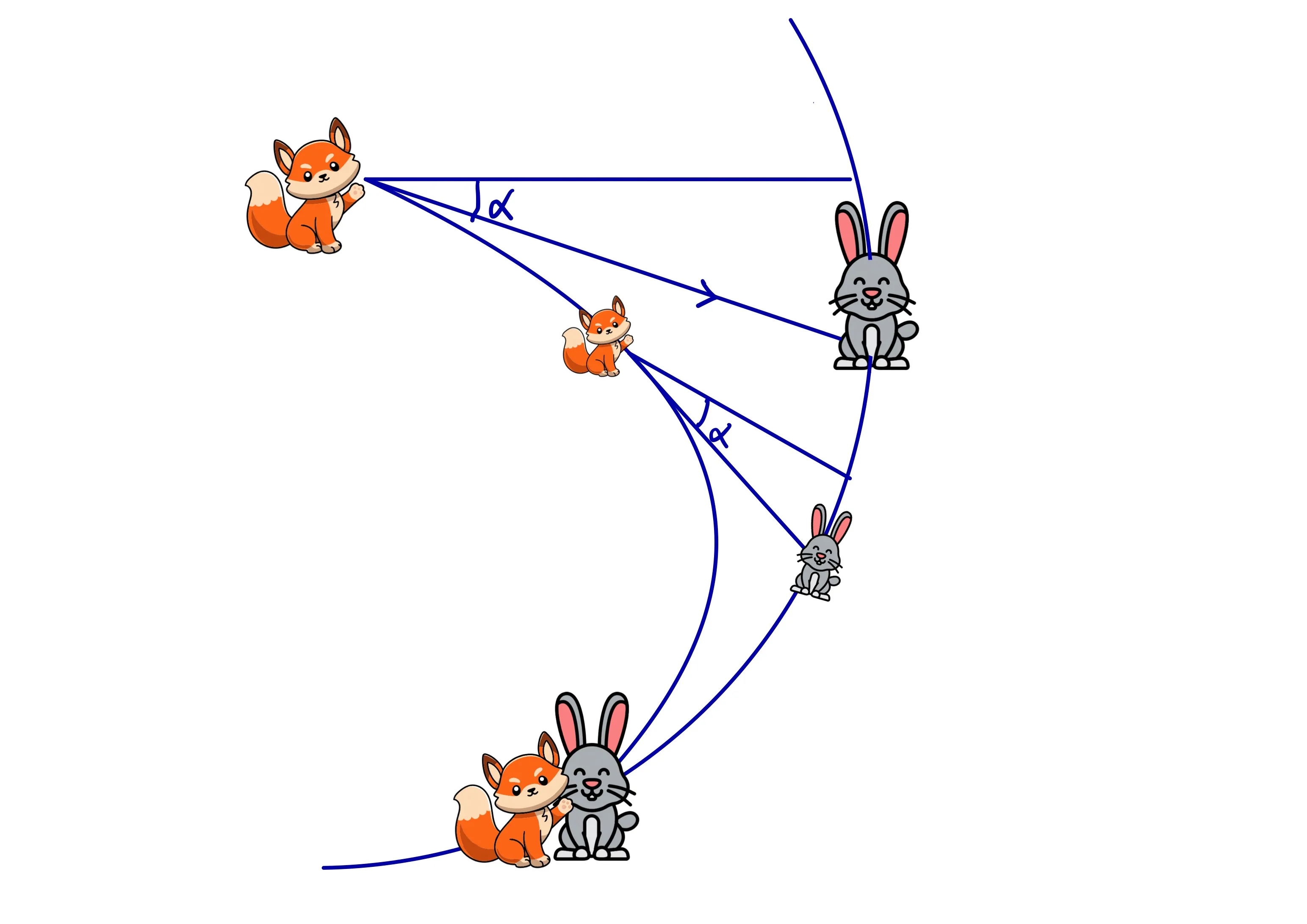

Picture multiple animals in a chain. A fox chases a rabbit, which chases another rabbit, which chases another. Each runs at angle \( \alpha \) relative to its pursuer.

Their initial positions form a circle. The radius of this circle is:

$$R = \frac{l/2}{\sin(\alpha/2)}$$

The center of the circle, call it \( O \), is the vertex of an isosceles triangle with vertex angle \( \alpha \) and the fox and rabbit as the other two vertices.

By symmetry, all the animals stay on a circle centered at \( O \) throughout the chase. They spiral inward toward \( O \). That’s where they meet.

There’s an equivalent way to see this. The rabbit’s velocity is always the fox’s velocity rotated by angle \( \alpha \). The meeting point \( O \) is the vertex of that isosceles triangle.

The Brute Force Method

The rabbit’s speed perpendicular to the fox-rabbit line is \( v\sin\alpha \). During time \( dt \), the fox’s direction changes by:

$$d\theta = \frac{v\sin\alpha}{l_t} dt$$

where \( l_t \) is the separation at time \( t \).

This gives us the rate of change of the fox’s velocity components:

$$\dot{v}_x = \frac{v \cdot v_y \sin\alpha}{l_t}$$

$$\dot{v}_y = -\frac{v \cdot v_x \sin\alpha}{l_t}$$

We know \( l_t = l – v(1 – \cos\alpha)t \). Multiply the equations by \( l_t \) and integrate from start to finish. After some algebra (squaring and adding), you get:

$$R = \sqrt{X^2 + Y^2} = \frac{l}{\sqrt{2(1 – \cos\alpha)}} = \frac{l/2}{\sin(\alpha/2)}$$

Same answer. The elegant method was easier, but both work. ∎

Solution: Part II

Now the rabbit runs in a straight line. The fox still chases directly. Does the fox catch up?

Spoiler: No. Not if \( \alpha \neq \pi \). They asymptotically approach a fixed separation.

The Elegant Method

Let \( A(t) \) and \( B(t) \) be the fox and rabbit positions. Let \( C(t) \) be the foot of the perpendicular from \( A \) to the rabbit’s path. Let \( \alpha_t \) be the angle at time \( t \) (it starts at \( \alpha \) and approaches 0).

Here’s the key insight. The rate at which distance \( AB \) decreases equals \( v – v\cos\alpha_t \). The rate at which distance \( CB \) increases equals \( v – v\cos\alpha_t \). They’re the same.

So \( AB + CB \) is constant throughout the chase.

Initially: \( AB + CB = l + l\cos\alpha \)

Finally (as \( t \to \infty \)): \( AB = CB = d \), so \( AB + CB = 2d \)

Setting them equal:

$$d = \frac{l(1 + \cos\alpha)}{2}$$

That’s the eventual separation. The fox gets close but never catches up.

The Differential Equations Method

The angle \( \alpha_t \) changes at rate:

$$\dot{\alpha}_t = -\frac{v\sin\alpha_t}{l_t}$$

The separation \( l_t \) changes at rate:

$$\dot{l}_t = -v(1 – \cos\alpha_t)$$

Divide the second by the first to eliminate time:

$$\frac{dl_t}{l_t} = \frac{(1 – \cos\alpha_t)}{\sin\alpha_t} d\alpha_t$$

Integrate both sides. You get:

$$\ln(l_t) = -\ln(1 + \cos\alpha_t) + \ln(k)$$

Which means:

$$l_t(1 + \cos\alpha_t) = k = \text{constant}$$

Apply initial conditions: \( k = l(1 + \cos\alpha) \)

As \( t \to \infty \), \( \alpha_t \to 0 \), so \( \cos\alpha_t \to 1 \):

$$l_\infty = \frac{l(1 + \cos\alpha)}{2}$$

Same answer. ∎

Edge Case

One exception. If \( \alpha = \pi \), the rabbit runs directly toward the fox. They meet halfway at time \( t = l/(2v) \). Not much of an escape strategy.

Key Insights

Part I produces a spiral. The fox catches the rabbit, and they meet at a predictable point determined purely by the initial geometry.

Part II produces an asymptotic approach. The fox gets arbitrarily close but never catches up (unless the rabbit is suicidal and runs toward the fox).

The difference? In Part I, the rabbit keeps adjusting, maintaining angle \( \alpha \) relative to the current pursuit direction. In Part II, the rabbit commits to a fixed path. That commitment saves it.

Both solutions showcase a beautiful trick: finding conserved quantities. In Part I, it’s the circular symmetry. In Part II, it’s \( AB + CB \). Find the right conserved quantity, and hard problems become easy.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a pursuit curve?

A pursuit curve is the path traced by an object that always moves directly toward a moving target. The fox in this problem follows a pursuit curve. These curves appear in missile guidance, predator-prey dynamics, and even in how some bacteria chase nutrients. The mathematics dates back to Leonardo da Vinci.

Why does the fox catch the rabbit in Part I but not Part II?

In Part I, the rabbit keeps adjusting its direction to maintain angle α relative to the fox. This creates a spiral where both animals converge to a central point. In Part II, the rabbit commits to a straight line. As the fox approaches, the angle between them shrinks toward zero, and the relative closing speed drops to zero. The rabbit escapes asymptotically.

What happens if α = 0?

If α = 0, the rabbit runs directly away from the fox. Both move at speed v along the same line. The gap never closes. In Part I, they stay separated by distance l forever. In Part II, same result. The fox can never catch a rabbit running straight away at equal speed.

What happens if α = π (rabbit runs toward fox)?

If α = π, the rabbit runs directly toward the fox. They close at combined speed 2v and meet at the midpoint in time l/(2v). This is the only case in Part II where the fox actually catches the rabbit. Not a great survival strategy for the rabbit.

Why do they spiral in Part I?

The rabbit’s velocity is always the fox’s velocity rotated by angle α. This constant rotation creates a spiral. If you imagine many animals in a chain, each chasing the next, their positions always lie on a shrinking circle. The center of that circle is where they all meet.

What’s the ‘slick method’ vs the ‘messier method’?

The slick method uses symmetry or conserved quantities to find the answer with minimal calculation. The messier method sets up and solves differential equations directly. Both give the same answer, but the slick method is faster and more elegant. Finding slick methods is half the fun of physics problems.

Where does this problem come from?

This version appears in David Morin’s “Introduction to Classical Mechanics,” an excellent textbook known for its challenging problems. Pursuit problems in general date back centuries. Pierre Bouguer studied them in 1732, and they’ve been a staple of mathematical physics ever since.

What’s the conserved quantity in Part II?

The sum AB + CB stays constant, where AB is the fox-rabbit distance and CB is the distance from the rabbit to the foot of the perpendicular from the fox. This conservation law makes the problem trivial once you spot it. Finding such quantities is a key skill in physics.

Do pursuit curves have real applications?

Yes. Missile guidance systems use pursuit and proportional navigation strategies. Predator-prey modeling in ecology uses similar mathematics. Even some robot navigation algorithms are based on pursuit curves. The mathematics of “chasing” appears anywhere one thing tracks another.

What if the fox is faster than the rabbit?

If the fox has speed v₁ and the rabbit has speed v₂ < v₁, the fox always catches the rabbit (unless α = 0 and v₁ = v₂). The catch time becomes l/(v₁ – v₂cosα) for Part I. The problem gets more interesting when speeds differ, but the same methods apply.

I am not sure what you mean by a “rabbit stop at angle alpha”. I’d like to solve the problem, but the only way I could get a hint is to read your solution. Frustrating.

[Fixed – Thanks]

I’ve reddit this post to get improvements. . But I don’t know why the redditors usually don’t comment. This is my notebook and errors are possible as a student.

Could you do a video with explanation ?