Jablonski Diagram – Consequences of Light Absorption

When a molecule absorbs light, something has to happen to that energy. It doesn’t just disappear. The molecule can use it for a chemical reaction. It can release it as heat. Or it can spit the light back out, sometimes in beautiful ways we call fluorescence and phosphorescence.

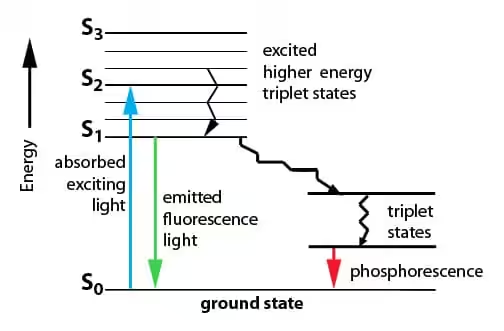

The Jablonski diagram maps all of this. It’s the roadmap for what happens to a molecule after it swallows a photon. If you want to understand fluorescence microscopy, solar cells, photodynamic therapy, or why your highlighter glows under UV light, you need to understand this diagram.

The Grotthus-Draper Law: Where It All Starts

Before we get into the diagram, we need to establish a basic rule. The Grotthus-Draper Law states:

Only light that is absorbed by a system can produce a photochemical change.

This sounds obvious, but it’s foundational. Light that passes straight through a sample does nothing. Light that bounces off does nothing. Only absorbed photons have a chance to cause chemistry.

But here’s the catch. Absorption doesn’t guarantee a photochemical reaction. The absorbed energy might take other paths entirely.

What Happens After Absorption

When a molecule absorbs a photon, the energy has to go somewhere. There are several possibilities.

Heat dissipation. The molecule converts electronic energy to vibrational energy, which spreads to surrounding molecules as heat. This is governed by the Beer-Lambert Law, which describes how light intensity decreases as it passes through an absorbing medium. Most absorbed light ends up as heat. It’s the default pathway.

Fluorescence. The molecule re-emits light almost immediately, within about \( 10^{-8} \) seconds (10 nanoseconds). The emitted light has lower energy (longer wavelength) than the absorbed light. This is why fluorescent materials glow with a different color than the exciting light.

Phosphorescence. The molecule emits light, but slowly. Sometimes the glow persists for seconds, minutes, or even hours after the light source is removed. Glow-in-the-dark toys use this phenomenon. The mechanism is fundamentally different from fluorescence, and understanding why requires the Jablonski diagram.

Photochemistry. The absorbed energy drives a chemical reaction. Bonds break. New bonds form. The molecule transforms. This is what the Grotthus-Draper Law is really about, but it’s actually the least common outcome for most absorbed photons.

Understanding Spin States: The Key to Everything

The Jablonski diagram won’t make sense without understanding electron spin. I’ll keep this as painless as possible.

Electrons have a property called spin. Think of it as a tiny magnetic orientation, either “up” or “down.” The quantum number is either \( +\frac{1}{2} \) or \( -\frac{1}{2} \).

Most stable molecules have an even number of electrons, and in the ground state, these electrons pair up with opposite spins. One up, one down. Their spins cancel out.

Spin Multiplicity

The total spin \( S \) of a molecule is the sum of all individual electron spins. When electrons are paired (one up, one down), their contributions cancel:

$$s_1 = +\frac{1}{2}, \quad s_2 = -\frac{1}{2}, \quad S = s_1 + s_2 = 0$$

The spin multiplicity is calculated as \( 2S + 1 \). When \( S = 0 \), the multiplicity is 1. We call this a singlet state.

Most molecules in their ground state are in the singlet configuration. We write it as \( S_0 \), meaning the ground singlet state.

What Changes When Light Is Absorbed

When a photon hits and gets absorbed, one electron jumps to a higher energy orbital. Now things get interesting.

The excited electron can maintain its original spin orientation (opposite to its former partner). In this case, the spins are still antiparallel, \( S = 0 \), and the molecule is in an excited singlet state (\( S_1 \), \( S_2 \), etc.).

Or the electron can flip its spin. Now both unpaired electrons have parallel spins (both up, or both down). The total spin becomes \( S = 1 \), and the multiplicity is \( 2(1) + 1 = 3 \). This is a triplet state (\( T_1 \), \( T_2 \), etc.).

The naming convention: \( S_0 \) is the ground singlet state. \( S_1 \), \( S_2 \), \( S_3 \) are excited singlet states. \( T_1 \), \( T_2 \), \( T_3 \) are triplet states. The subscript indicates the energy level.

Don’t confuse \( S \) (total spin quantum number) with \( S_n \) (singlet states). Unfortunately, the notation uses the same letter for both.

The Jablonski Diagram Explained

Now we can actually read the diagram.

The vertical axis represents energy. Horizontal lines represent electronic states. The thick lines are electronic energy levels. The thin lines stacked above each electronic level are vibrational sublevels.

Singlet states (\( S_0 \), \( S_1 \), \( S_2 \)) are on the left. Triplet states (\( T_1 \), \( T_2 \)) are on the right. The triplet states are always lower in energy than the corresponding singlet states. This is Hund’s rule at work: parallel spins experience less electron-electron repulsion.

Absorption (The Fast Part)

Light absorption is nearly instantaneous, about \( 10^{-15} \) seconds (a femtosecond). During this time, only the electrons move. The heavier nuclei don’t have time to respond. This is the Franck-Condon principle.

Absorption is shown as a straight vertical arrow pointing up. The molecule jumps from \( S_0 \) to some vibrational level of \( S_1 \) or \( S_2 \), depending on the photon energy.

Direct excitation to triplet states is “spin-forbidden.” The transition requires a spin flip, which photons can’t directly cause. So absorption always goes to singlet excited states.

Vibrational Relaxation

Within picoseconds (\( 10^{-12} \) seconds), the molecule loses vibrational energy to its surroundings as heat. It cascades down through vibrational levels until it reaches the lowest vibrational level of the excited electronic state.

This is shown as wavy arrows pointing down within a single electronic state. It’s fast and nonradiative (no light emitted).

Internal Conversion

If the molecule is in \( S_2 \) or higher, it can drop to \( S_1 \) through internal conversion. This is a nonradiative transition between electronic states of the same multiplicity.

Internal conversion happens when vibrational levels of two electronic states overlap. The molecule essentially “slides” from one electronic state to another. It’s extremely fast, typically \( 10^{-12} \) seconds or less.

This is why fluorescence almost always occurs from \( S_1 \), regardless of which singlet state was initially excited. The molecule relaxes to \( S_1 \) before it has a chance to emit light. This observation is called Kasha’s Rule.

Fluorescence

From the lowest vibrational level of \( S_1 \), the molecule can emit a photon and drop back to \( S_0 \). This is fluorescence.

The emitted photon has less energy than the absorbed photon. Some energy was lost to vibrational relaxation. This energy difference is the Stokes shift, and it’s why fluorescent materials emit at longer wavelengths than they absorb.

Fluorescence is fast, typically \( 10^{-9} \) to \( 10^{-7} \) seconds (nanoseconds). The emission stops almost immediately when you turn off the excitation source.

On the diagram, fluorescence is shown as a straight vertical arrow pointing down from \( S_1 \) to various vibrational levels of \( S_0 \).

Intersystem Crossing

Here’s where it gets interesting. The molecule in \( S_1 \) can sometimes cross over to \( T_1 \). This requires a spin flip, which is technically “forbidden.” But forbidden doesn’t mean impossible. It just means slow and unlikely.

Heavy atoms (like bromine, iodine, or metals) dramatically increase the rate of intersystem crossing through spin-orbit coupling. The heavy atom effect is used intentionally in phosphorescent materials and photodynamic therapy drugs.

On the diagram, intersystem crossing is shown as a horizontal wavy arrow from \( S_1 \) to \( T_1 \).

Phosphorescence

Once in the triplet state, the molecule is stuck. Returning to \( S_0 \) requires another spin flip, which is again forbidden. The molecule can sit in \( T_1 \) for a long time: milliseconds, seconds, even minutes.

Eventually, it does emit a photon and drops to \( S_0 \). This is phosphorescence. The long lifetime is why glow-in-the-dark materials keep glowing after the light is removed.

Phosphorescence emission has even lower energy (longer wavelength) than fluorescence because \( T_1 \) is lower in energy than \( S_1 \).

On the diagram, phosphorescence is shown as a straight arrow from \( T_1 \) to \( S_0 \).

The Competition: Why Not Every Molecule Fluoresces

All these processes compete with each other. A molecule in \( S_1 \) can:

Fluoresce (emit light, return to \( S_0 \))

Undergo internal conversion to \( S_0 \) (no light, just heat)

Cross to \( T_1 \) (intersystem crossing)

React chemically (photochemistry)

Transfer energy to another molecule (quenching)

The quantum yield of fluorescence is the fraction of absorbed photons that result in fluorescence emission. For a good fluorophore like fluorescein, it’s around 0.9 (90% of absorbed photons are re-emitted). For most molecules, it’s much lower.

Timescales: The Key to Understanding

The timescales make everything click:

Absorption: \( 10^{-15} \) s (femtoseconds)

Vibrational relaxation: \( 10^{-12} \) s (picoseconds)

Internal conversion: \( 10^{-12} \) s (picoseconds)

Fluorescence: \( 10^{-9} \) to \( 10^{-7} \) s (nanoseconds)

Intersystem crossing: \( 10^{-8} \) to \( 10^{-3} \) s (variable)

Phosphorescence: \( 10^{-3} \) to \( 10^{2} \) s (milliseconds to minutes)

Vibrational relaxation and internal conversion are faster than fluorescence. That’s why Kasha’s Rule works. The molecule always relaxes to \( S_1 \) before it can emit from \( S_2 \).

Phosphorescence is orders of magnitude slower than fluorescence because it requires a forbidden spin flip.

Practical Applications

The Jablonski diagram isn’t just academic. It explains real technology.

Fluorescence microscopy. Biologists use fluorescent labels to visualize specific proteins or structures in cells. Understanding the Jablonski diagram helps you choose the right fluorophore and filter sets.

OLED displays. Organic light-emitting diodes use both fluorescent and phosphorescent emitters. Phosphorescent OLEDs can theoretically harvest both singlet and triplet excitons, giving higher efficiency.

Photodynamic therapy. Some cancer treatments use molecules that undergo efficient intersystem crossing. The triplet state reacts with oxygen to produce reactive oxygen species that kill tumor cells.

Solar cells. Singlet fission, where one singlet exciton splits into two triplet excitons, could potentially double the efficiency of certain solar cells. The Jablonski diagram is the starting point for understanding this process.

Forensics. Crime scene investigators use fluorescent powders and alternative light sources to detect fingerprints, biological fluids, and trace evidence.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a Jablonski diagram?

A Jablonski diagram is an energy level diagram that shows what happens to a molecule after it absorbs light. It maps electronic states (singlet and triplet), vibrational levels, and the various pathways for energy dissipation including fluorescence, phosphorescence, internal conversion, and intersystem crossing.

What is the difference between fluorescence and phosphorescence?

Fluorescence is fast light emission (nanoseconds) from singlet excited states. Phosphorescence is slow light emission (milliseconds to minutes) from triplet states. Phosphorescence requires a spin flip, which is quantum mechanically forbidden and therefore slow. That’s why glow-in-the-dark materials keep glowing after the light source is removed.

What is spin multiplicity?

Spin multiplicity equals 2S+1, where S is the total electron spin. When electrons are paired (opposite spins), S=0 and multiplicity is 1 (singlet). When two electrons have parallel spins, S=1 and multiplicity is 3 (triplet). The name refers to how many ways the state can orient in a magnetic field.

Why is the triplet state lower in energy than the singlet?

Electrons with parallel spins (triplet state) must occupy different regions of space due to the Pauli exclusion principle. This reduces electron-electron repulsion, lowering the energy. This is a consequence of Hund’s rule and explains why T₁ is always below S₁ on a Jablonski diagram.

What is Kasha’s Rule?

Kasha’s Rule states that fluorescence occurs from the lowest excited singlet state (S₁), regardless of which state was initially excited. This happens because internal conversion and vibrational relaxation are faster than fluorescence, so the molecule always relaxes to S₁ before it can emit light.

What is the Stokes shift?

The Stokes shift is the difference in wavelength between absorption and emission maxima. Emitted light always has longer wavelength (lower energy) than absorbed light because energy is lost to vibrational relaxation before emission occurs. Larger Stokes shifts make fluorescence easier to detect because excitation and emission don’t overlap.

What is intersystem crossing?

Intersystem crossing is the transition from a singlet state to a triplet state (or vice versa). It requires a spin flip, which is formally forbidden by quantum selection rules. Heavy atoms like bromine, iodine, or metals increase intersystem crossing rates through spin-orbit coupling. This is called the heavy atom effect.

What is the Grotthus-Draper Law?

The Grotthus-Draper Law states that only absorbed light can cause a photochemical change. Light that passes through or reflects off a substance has no effect. But absorption alone doesn’t guarantee chemistry. The absorbed energy might be released as fluorescence, phosphorescence, or heat instead of driving a reaction.

What is quantum yield of fluorescence?

Quantum yield is the ratio of photons emitted to photons absorbed. A quantum yield of 1.0 means every absorbed photon results in an emitted photon (100% efficiency). Good fluorophores like fluorescein have quantum yields around 0.9. Most molecules have much lower values because competing processes like internal conversion and intersystem crossing drain energy.

Why does phosphorescence last so long?

Phosphorescence requires a transition from triplet to singlet ground state, which means an electron must flip its spin. This is quantum mechanically forbidden (low probability), so the triplet state is long-lived. The molecule can sit in T₁ for milliseconds to hours before finally emitting. That’s why glow-in-the-dark toys work.

you wrote S=0, 2S+1=3 which is obviously wrong ;)

Fixed thanks!!

[Gaurav Tiwari]

hi