Three Children, Two Friends and One Mathematical Puzzle

This is one of my favorite logic puzzles. It looks simple at first. Then you realize you’re missing something. And when the solution clicks, it’s genuinely satisfying.

I’ve used this puzzle to explain logical reasoning to students for years. It teaches you to pay attention to what you don’t know as much as what you do.

Let me walk you through it.

The Puzzle

Two close friends, Robert and Thomas, meet again after several years apart.

- Robert: I’m married now and have three children.

- Thomas: That’s great! How old are they?

- Robert: Guess. I’ll give you clues. The product of my children’s ages is 36.

- Thomas: Hmm. That’s not enough to figure it out. Give me another clue.

- Robert: See the number on that house across the street? The sum of their ages equals that number.

- Thomas: [thinks for a moment] I still can’t determine their ages.

- Robert: My oldest child has red hair.

- Thomas: Oh, the oldest one? Now I’ve got it. I know each of their ages.

The question: What are the ages of Robert’s three children? And how did Thomas figure it out?

Take a minute to work through it before reading further. The fun is in the solving.

Why This Puzzle Is Brilliant

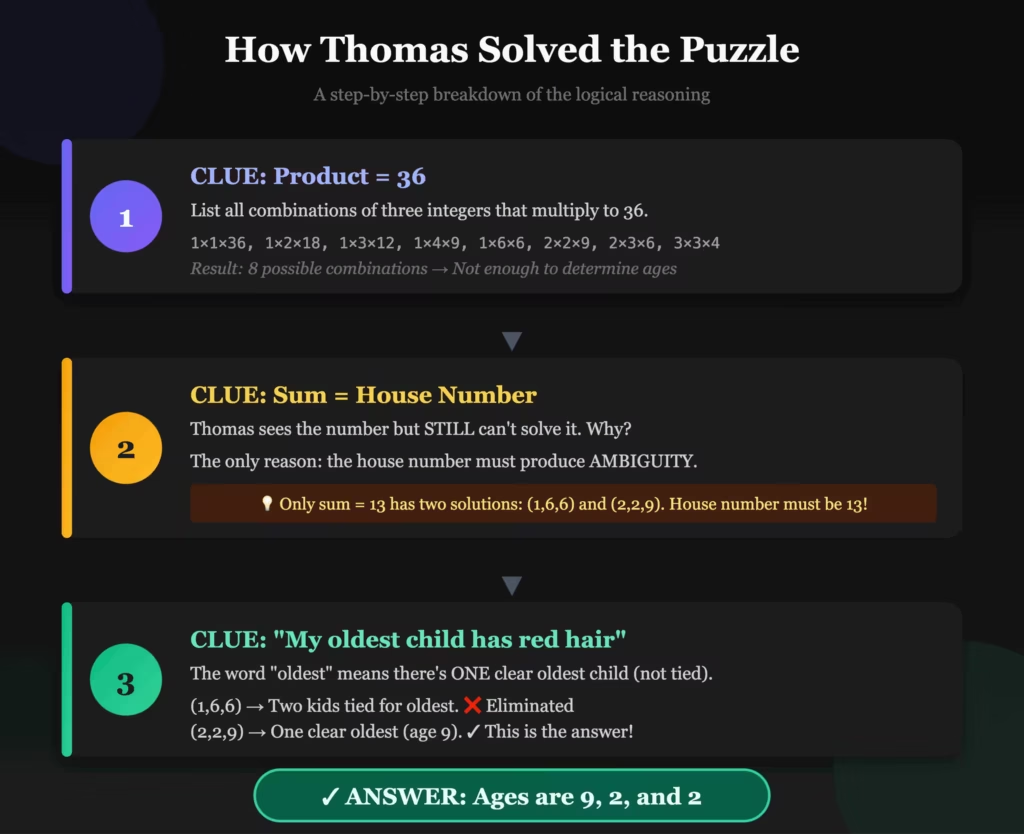

The puzzle isn’t just about math. It’s about understanding why someone can’t solve a problem with the information given.

Thomas is smart. He knows the product (36) and the sum (the house number). That should be enough to find three numbers. But it wasn’t.

Why not?

That’s the real puzzle.

Finding All Possible Age Combinations

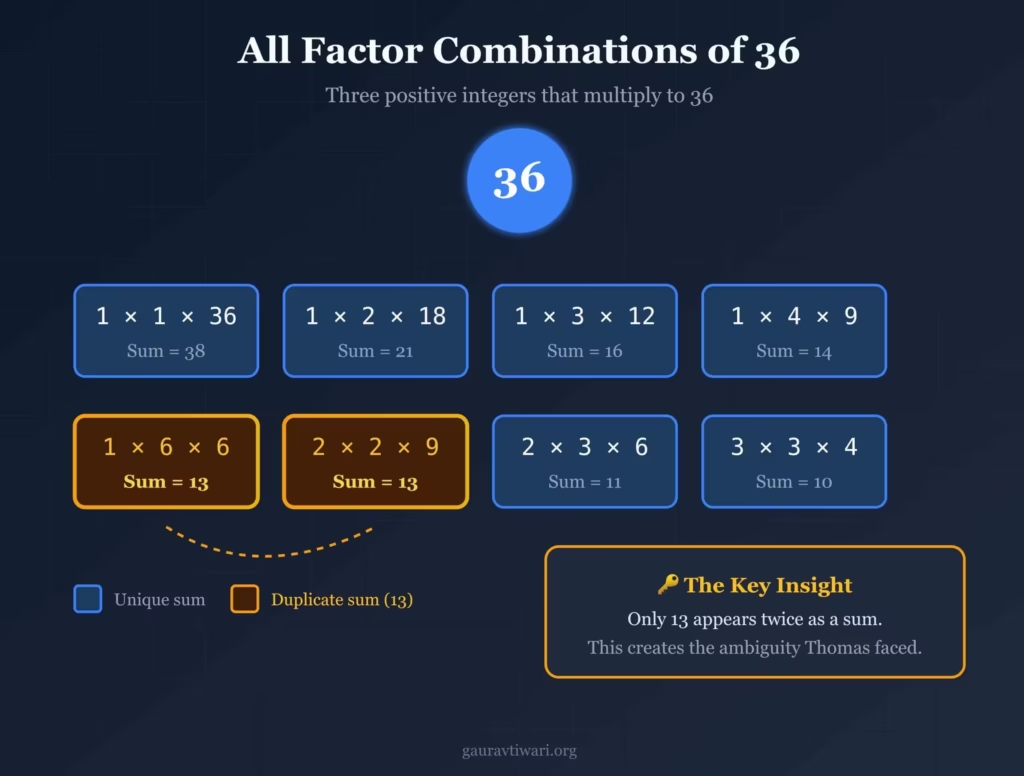

Start by listing every combination of three positive integers that multiply to 36. Assuming we’re dealing with whole number ages (reasonable for children), here are all the possibilities:

| First Child | Second Child | Third Child | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 36 | 38 |

| 1 | 2 | 18 | 21 |

| 1 | 3 | 12 | 16 |

| 1 | 4 | 9 | 14 |

| 1 | 6 | 6 | 13 |

| 2 | 2 | 9 | 13 |

| 2 | 3 | 6 | 11 |

| 3 | 3 | 4 | 10 |

Eight possible combinations. Eight different sums.

Well, not quite eight different sums.

The Key Insight

Look at that table again. Notice anything?

Two combinations have the same sum: 13.

Both 1-6-6 and 2-2-9 add up to 13.

This is everything.

Thomas could see the house number. If that number had been 38, or 21, or 16, or any unique sum, he would have immediately known the answer. Only one combination produces each of those sums.

But Thomas said he still couldn’t figure it out after seeing the house number.

The only way that makes sense is if the house number was 13. Because 13 is the only sum with two valid combinations. Thomas was stuck between 1-6-6 and 2-2-9.

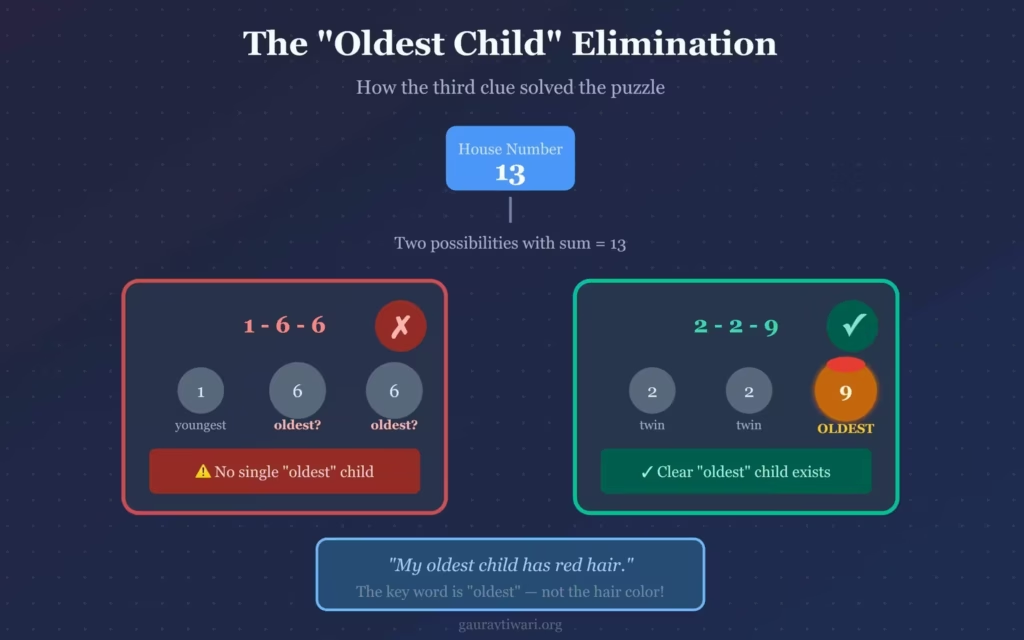

The Red Hair Revelation

Robert’s third clue sounds almost irrelevant: “My oldest child has red hair.”

The hair color doesn’t matter at all. What matters is the word oldest.

If the ages were 1, 6, and 6, there wouldn’t be a single oldest child. There would be two children tied for oldest (the twins who are both 6).

But Robert specifically referred to “my oldest child” as a single person. That means there is a definitive oldest.

Only one of our remaining options has a clear oldest: 2, 2, and 9.

The 9-year-old is the oldest (the redhead). The younger two are both 2.

Thomas got it.

The Answer

Robert’s children are 9, 2, and 2 years old.

The oldest child is 9 (with red hair, apparently). The two younger children are 2-year-old twins.

Quick verification:

- Product: 9 × 2 × 2 = 36 ✓

- Sum: 9 + 2 + 2 = 13 (the house number) ✓

- Single oldest child: Yes, the 9-year-old ✓

What Makes This Puzzle Educational

I love this puzzle because it teaches meta-reasoning. You’re not just solving for unknowns. You’re reasoning about why someone else couldn’t solve it.

Thomas’s inability to answer after the second clue is itself information. It tells you the house number must create ambiguity. And only 13 does that.

This kind of thinking shows up everywhere in real problem-solving. In debugging code, you ask “why didn’t this work?” In business, you analyze why a strategy failed. The absence of a solution is data.

Common Mistakes People Make

Forgetting about the second clue failure. Some people try to solve it using only the product and the “oldest child” clue, ignoring that Thomas couldn’t solve it with the house number. But that failure is the most important clue.

Assuming the house number is given. The puzzle never tells us the house number directly. We have to deduce it from Thomas’s confusion.

Overcomplicating the “red hair” clue. Some people try to factor in probability of hair color, or wonder if it’s a trick. It’s not. The only relevant word is “oldest.”

Missing the duplicate sum. If you calculate the sums and don’t notice that 13 appears twice, you’ll never crack it.

Variations of This Puzzle

This puzzle has been around for decades in various forms. Sometimes it’s a census taker at a door. Sometimes the product is different (72 is common). Sometimes the third clue mentions a “youngest” child instead.

The core mechanism is always the same: create exactly one ambiguous sum, then resolve the ambiguity with information about birth order.

If you want to create your own version, find a number with multiple factor triplets that share a sum. 36 works well. So does 72 (which has more combinations and is harder).

Try These Next

If you enjoyed this, here are similar logic puzzles worth exploring:

- The Blue Eyes Puzzle: 100 people on an island all have blue eyes but don’t know their own eye color. A visitor announces that at least one person has blue eyes. What happens? (This one is famously difficult.)

- The Two Doors Riddle: Two doors, one leads to freedom, one to death. One guard always lies, one always tells the truth. You can ask one question to one guard. What do you ask?

- The Hardest Logic Puzzle Ever: Three gods named True, False, and Random. You must identify them by asking yes-no questions, but Random answers randomly. Good luck.

Source

This puzzle is a modified version of one originally published in Science Reporter Magazine. It’s become a classic in recreational mathematics and appears in countless puzzle books and math competitions.

The elegance is in its simplicity. Three clues. Basic arithmetic. And a solution that requires you to think about thinking.

That’s what good puzzles do.

FAQs

What is the Three Children puzzle about?

The Three Children puzzle is a classic logic problem where Robert tells his friend Thomas that his three children’s ages multiply to 36 and add up to a visible house number. Despite these clues, Thomas can’t determine the ages until Robert mentions his oldest child has red hair. The puzzle requires logical deduction and meta-reasoning to find the unique solution.

What are the ages of Robert’s three children?

The ages are 9, 2, and 2. The oldest child (the redhead) is 9 years old, and the two younger children are both 2 years old. These three ages multiply to 36 (9 × 2 × 2 = 36) and add up to 13, which was the house number.

Why couldn’t Thomas figure out the ages after learning the house number?

Thomas couldn’t determine the ages because the house number must have been 13, which is the only sum that appears more than once among possible age combinations. Both 1-6-6 and 2-2-9 add up to 13. For any other house number, only one combination exists, and Thomas would have solved it immediately.

What does the ‘oldest child has red hair’ clue actually mean?

The red hair color is irrelevant. The key word is ‘oldest,’ indicating there is a single oldest child. This eliminates 1-6-6 (where two children share the oldest age as twins) and confirms the answer is 2-2-9, where there’s one clear oldest child who is 9 years old.

What are all the age combinations that multiply to 36?

Assuming whole number ages, the eight combinations are: 1-1-36 (sum 38), 1-2-18 (sum 21), 1-3-12 (sum 16), 1-4-9 (sum 14), 1-6-6 (sum 13), 2-2-9 (sum 13), 2-3-6 (sum 11), and 3-3-4 (sum 10). Only two combinations share the same sum of 13.

Why is the number 13 significant in this puzzle?

The number 13 is the only sum that appears twice among all valid age combinations. Both 1-6-6 and 2-2-9 equal 13. This ambiguity is why Thomas couldn’t solve the puzzle with just the first two clues and needed the third clue about the oldest child to distinguish between these possibilities.

What type of reasoning does this puzzle teach?

This puzzle teaches meta-reasoning, which means thinking about why someone else couldn’t solve a problem. Thomas’s inability to answer after the second clue is itself crucial information, revealing the house number must create ambiguity. This skill applies to debugging code, analyzing business failures, and real-world problem-solving.

Where did the Three Children puzzle originate?

This version is a modified form of a puzzle originally published in Science Reporter Magazine. The puzzle has appeared in various forms for decades, sometimes featuring a census taker or different products like 72. It’s become a classic in recreational mathematics and math competitions worldwide.

Disclaimer: This site is reader‑supported. If you buy through some links, I may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. I only recommend tools I trust and would use myself. Your support helps keep gauravtiwari.org free and focused on real-world advice. Thanks. — Gaurav Tiwari

Amazing!!

But I am sure I would have never been able to solve this, if I was being questioned:/

Why not the answer will be 2,3 and 6 because their product will be 36 and because of i am not there than how i know the house no.