Nucleic Acid

Nucleic acids are polynucleotides, and along with polysaccharides and polypeptides, they form the true macromolecular fraction of every living cell. You’ll find them working alongside proteins as the main constituents of chromosomes. Their central job is transmitting characters from one generation to the next, a phenomenon you know as heredity.

Structure of Nucleic Acids

The building blocks of nucleic acids are nucleotides. Each nucleotide has three chemically distinct components: a heterocyclic compound (the nitrogenous base), a monosaccharide (the sugar), and a phosphoric acid or phosphate residue.

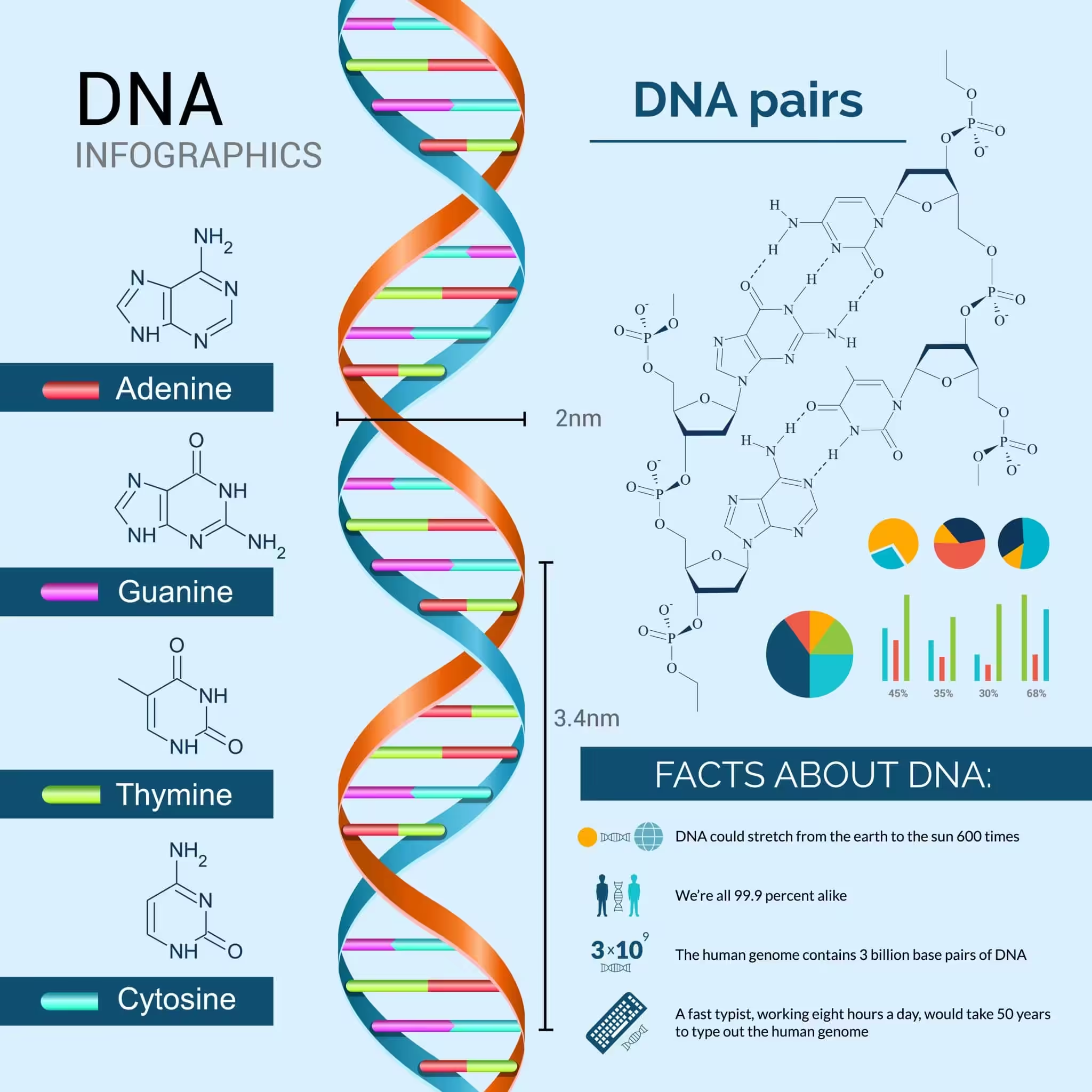

The nitrogenous bases you need to remember are adenine, guanine, uracil, cytosine, and thymine. Adenine and guanine are substituted purines, while the remaining three are substituted pyrimidines. The sugar in polynucleotides is either beta-D-ribose or beta-D-2-deoxyribose.

Here is the key distinction: a nucleic acid containing deoxyribose is called deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), and one that contains ribose is called ribonucleic acid (RNA). With that foundation in place, let’s explore each component in detail.

Purines, Pyrimidines, and Nucleosides

Before you can understand nucleic acids properly, you need to get comfortable with two classes of heterocyclic bases: the purines and the pyrimidines. Pyrimidines are six-membered heterocyclic rings, whereas purines contain both a five-membered and a six-membered ring fused together. Because nitrogen atoms sit within these rings, the compounds are classified as heterocyclics and behave as bases.

In nature, you’ll encounter five important bases in nucleic acids: two purine bases (adenine and guanine) and three pyrimidine bases (cytosine, thymine, and uracil). These natural bases differ from each other in their ring substituents. Some modified versions, such as 5-fluorouracil, are used in cancer chemotherapy.

Every base has a lowermost nitrogen bonded to a hydrogen and two carbons. This -NH- group shares chemical similarities with an alcohol (-OH) group. Just as two sugar molecules can link when an -OH group of one monosaccharide reacts with another, a purine or pyrimidine can bond to a sugar molecule through that -NH- group.

When a purine or pyrimidine base links to a sugar molecule (usually beta-D-ribose or beta-D-2-deoxyribose), you get a nucleoside. The bond forms between C-1 of the sugar and either the purine nitrogen at position 9 or the pyrimidine nitrogen at position 1, releasing a water molecule in the process.

The naming of nucleosides reflects the parent base. For example, adenine combined with beta-D-ribose yields adenosine, while cytosine combined with beta-D-2-deoxyribose yields deoxycytidine.

Nucleotides

Nucleotides are phosphate esters of nucleosides. Think of them as nucleosides with at least one phosphate group attached. The ester linkage can form with the hydroxyl group at position 2, 3, or 5 of ribose, or at position 3 or 5 of deoxyribose. When two or more phosphate residues link together, you get a high-energy phosphate anhydride bond.

Why should you care about that bond? Because nucleotides drive energy transfer in your cells. Adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) are the most important examples. Part of the energy released from biological oxidation of the food you eat is stored in the phosphate anhydride bonds of ADP and ATP.

Your body releases that stored energy by reversibly hydrolysing these high-energy bonds, yielding about 35 kJ per mole of ATP. Every natural process, from muscle contraction and nerve impulse conduction to vision and your heartbeat, depends on the energy obtained from ATP.

Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA)

DNA is the molecule that started the dance of life on earth. It is a long polymer of deoxyribonucleotides, and its length is usually expressed as the number of nucleotides or base pairs it contains. The haploid content of human DNA is 3.3 x 109 base pairs, which gives you a sense of how enormous this molecule truly is.

Friedrich Miescher first discovered DNA in 1869, naming it “nuclein” because he found it as an acidic substance in the nucleus. The real breakthrough came in 1953, when James Watson and Francis Crick used X-ray diffraction data from Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin to propose their now-famous double helical model. This work earned Watson, Crick, and Wilkins the Nobel Prize.

A cornerstone of their model was base pairing between the two polynucleotide strands. This was consistent with Erwin Chargaff’s observation that in double-stranded DNA, the ratio of adenine to thymine and guanine to cytosine always equals one. You’ll see this referred to as Chargaff’s rule.

Here are the key features of the Watson-Crick model that you should know:

- DNA consists of two polynucleotide chains with a sugar-phosphate backbone on the outside and nitrogenous bases projecting inward.

- The two chains run in anti-parallel polarity: one strand runs 5′ to 3′, and the other runs 3′ to 5′.

- Bases on opposite strands pair through hydrogen bonds. Adenine pairs with thymine via two H-bonds, and guanine pairs with cytosine via three H-bonds. A purine always sits opposite a pyrimidine, keeping the helix width uniform.

- The two chains coil in a right-handed fashion. The pitch of the helix is 3.4 nm, with roughly 10 base pairs per turn. The distance between consecutive base pairs is about 0.34 nm.

- Base pairs stack on top of each other within the helix. This stacking, combined with hydrogen bonding, gives the double helix its remarkable stability.

Packaging of DNA Within the Nucleus

If you stretched out the DNA from a single human cell, it would measure roughly 2.2 metres. The nucleus of a typical cell, on the other hand, is only about 10-6 m across. So how does such a long molecule fit inside such a tiny space?

Even in prokaryotes, which lack a well-defined nucleus, DNA is not scattered randomly through the cell. Because DNA carries a negative charge, it is organized into large loops held together by positively charged proteins in a region called the nucleoid.

Eukaryotes take packaging a step further with a set of positively charged, basic proteins called histones. These proteins are rich in lysine and arginine, two amino acids that carry positive charges in their side chains. Eight histone molecules come together to form a histone octamer.

The negatively charged DNA wraps around this positively charged histone octamer, forming a structure called a nucleosome. Each nucleosome holds about 200 base pairs of DNA. When you view nucleosomes under an electron microscope, they have a characteristic “beads-on-string” appearance.

This beads-on-string structure is further packaged into chromatin fibres, which coil and condense during the metaphase stage of cell division to form the chromosomes you see in textbook diagrams. This higher-level packaging requires an additional set of proteins collectively called non-histone chromosomal (NHC) proteins.

Different Forms of DNA

Scientists have identified more than a dozen structural forms of DNA, each named after a letter of the alphabet. Here are the ones you should know:

- B-DNA – The standard form with right-handed coiling and 10 base pairs per turn. This is the structure Watson and Crick described.

- A-DNA – Contains 11 base pairs per turn. The base pairs are tilted rather than perpendicular to the helical axis.

- C-DNA – Resembles B-DNA but has only 9 base pairs per turn.

- D-DNA – Similar to B-DNA but with 8 base pairs per turn.

- Z-DNA – The standout exception. Unlike all the forms above, Z-DNA demonstrates left-handed coiling.

Ribonucleic Acid (RNA)

RNA is usually single-stranded, though you will encounter double-stranded RNA in certain viruses like the rice dwarf virus and reovirus. There is strong evidence that RNA was the first genetic material on earth. Essential life processes such as metabolism, translation, and splicing all evolved around RNA, and it served as both a genetic material and an enzymatic catalyst in primitive living systems.

However, because RNA acted as a catalyst, it was chemically reactive and inherently unstable. DNA eventually evolved from RNA through chemical modifications (thymine replacing uracil, for instance) and gained special repair mechanisms that made it far more stable. That stability is why DNA took over as the primary genetic material in most living organisms. Today, RNA still serves as the genetic material in certain groups of viruses.

There are three types of non-genetic RNA you should understand:

Messenger RNA (mRNA)

Discovered by Jacob and Monod in 1961, mRNA is synthesized in the nucleus and carries the genetic information needed for protein synthesis. Think of it as the blueprint that travels from your DNA to the ribosome, telling the cell exactly which protein to build.

Ribosomal RNA (rRNA)

rRNA is the largest type of RNA and makes up about 80% of the total cellular RNA. You’ll find it in ribosomes, the molecular machines where protein synthesis actually takes place. It provides the structural framework that holds the ribosome together and plays a direct role in catalysing peptide bond formation.

Transfer RNA (tRNA)

Also known as soluble RNA or adaptive RNA, tRNA is the smallest type of RNA, accounting for roughly 10-15% of total cellular RNA. You’ll find tRNA molecules in the cytoplasm, and there are as many types as there are amino acids used in protein synthesis (typically 20). Their job is to pick up specific amino acids from the cytoplasm and deliver them to the ribosome during translation.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between DNA and RNA?

DNA contains the sugar deoxyribose and uses thymine as one of its bases, while RNA contains ribose and uses uracil instead of thymine. DNA is typically double-stranded and serves as the long-term storage of genetic information, whereas RNA is usually single-stranded and plays active roles in protein synthesis, gene regulation, and catalysis.

What is Chargaff’s rule and why is it important?

Chargaff’s rule states that in any double-stranded DNA molecule, the amount of adenine equals the amount of thymine, and the amount of guanine equals the amount of cytosine. This 1:1 ratio was a crucial clue that led Watson and Crick to propose complementary base pairing in their double helix model of DNA.

What is a nucleosome and how does it help package DNA?

A nucleosome is a structure formed when a stretch of about 200 base pairs of DNA wraps around a histone octamer (a unit of eight histone proteins). Nucleosomes are the repeating units of chromatin and give it a beads-on-string appearance under the electron microscope. This packaging allows roughly 2.2 metres of DNA to fit inside a cell nucleus that is only about one-millionth of a metre across.

Why is RNA considered the first genetic material?

RNA can both store genetic information and catalyse chemical reactions (as ribozymes), making it capable of supporting primitive life on its own. Essential processes like metabolism, translation, and splicing all evolved around RNA. DNA later evolved from RNA with chemical modifications and repair mechanisms that made it more stable and better suited as a permanent genetic store.

What are the three types of RNA and what do they do?

The three main types of non-genetic RNA are messenger RNA (mRNA), which carries genetic instructions from DNA to the ribosome; ribosomal RNA (rRNA), which forms the structural and catalytic core of ribosomes where proteins are assembled; and transfer RNA (tRNA), which delivers specific amino acids to the ribosome during protein synthesis.

How is Z-DNA different from the standard B-DNA form?

B-DNA is the standard right-handed double helix with 10 base pairs per turn, which is the form Watson and Crick described. Z-DNA, in contrast, has a left-handed helical twist, making it structurally unique among all known DNA forms. Z-DNA is thought to play a role in gene regulation, and it tends to form in regions rich in alternating purine-pyrimidine sequences.

This is an excellent overview of nucleic acids. The level of detail is perfect for undergraduate students.

This page on nucleic acids is now my primary reference for revision. Well-written, accurate, and free. Can’t ask for more.

This page on nucleic acids is now my primary reference for revision. Well-written, accurate, and free. Can’t ask for more.

Shared this with my entire study group. The DNA vs RNA structure section in particular cleared up a lot of confusion.

I’m studying for my biology exam and this article saved me. Everything about nucleic acids is covered so clearly.

As a medical student, understanding nucleic acids at the molecular level is crucial. This resource nails that balance between depth and clarity.

Your explanation of DNA vs RNA structure is the clearest I’ve seen anywhere. I finally understand how it all fits together.

I teach introductory biology and often point my students to this resource. The explanations are accurate and accessible.

The real-world examples make nucleic acids so much more interesting. I actually enjoyed studying this chapter now.

The classification and types you describe for nucleic acids are presented much more clearly here than in my textbook.

The FAQs at the end are really useful. They cover the exact questions students typically ask about nucleic acids.

Thank you for including both the basic definitions and the deeper biochemistry. Covers everything from intro to advanced level.

Your explanation of DNA vs RNA structure is the clearest I’ve seen anywhere. I finally understand how it all fits together.

As a medical student, understanding nucleic acids at the molecular level is crucial. This resource nails that balance between depth and clarity.

Thank you for including both the basic definitions and the deeper biochemistry. Covers everything from intro to advanced level.