The Lindemann Theory of Unimolecular Reactions

Bimolecular reactions make sense. Two molecules collide, bonds break, new bonds form. Simple.

But unimolecular reactions? A single molecule just… reacts? Where does the energy come from? This puzzle bothered chemists for years until F.A. Lindemann proposed an elegant solution in 1922.

The Problem with Unimolecular Reactions

Collision theory explains bimolecular reactions beautifully.

When two molecules A and B collide, their relative kinetic energy exceeds the threshold energy. The collision breaks existing bonds and forms new ones.

But what about a reaction like \( A \longrightarrow P \)? Just one molecule turning into product?

If molecule A needs activation energy, it must get that energy from somewhere. The obvious answer: collision with another molecule. But that would make it a second-order reaction. And experimentally, many unimolecular gas reactions follow first-order kinetics.

Something didn’t add up.

Lindemann’s Mechanism

Frederick Lindemann proposed a clever two-step mechanism in 1922. Here’s how it works.

For a unimolecular reaction \( A \longrightarrow P \), Lindemann suggested:

Step 1 (Activation): \( A + A \rightleftharpoons A^* + A \)

The forward rate constant is \( k_f \) and the backward rate constant is \( k_b \).

Step 2 (Reaction): \( A^* \longrightarrow P \) with rate constant \( k_{f_2} \)

The \( A^* \) is an energized molecule. It’s picked up enough vibrational energy to react. Think of it as a molecule that’s been “wound up” and ready to spring.

Important distinction: \( A^* \) is not an activated complex. It’s just a regular molecule sitting in a high vibrational energy state. The energy exceeds the threshold needed for reaction, but the molecule hasn’t committed to reacting yet.

Where the Energy Comes From

In Step 1, two A molecules collide. Kinetic energy from the second molecule transfers into vibrational energy of the first. That’s your energized \( A^* \).

The collision partner doesn’t have to be another A molecule. It could be a product molecule, an inert gas, or anything else present in the system. It just doesn’t appear in the overall stoichiometry \( A \longrightarrow P \).

The Time Lag

Here’s the key insight. There’s a delay between energization and reaction.

Once \( A^* \) forms, two things can happen:

It can collide with another molecule and lose its energy (de-energization back to A). The vibrational energy converts back to kinetic energy of the collision partner.

Or it can react. The excess vibrational energy breaks the right bonds and forms product P.

This competition between de-energization and reaction is what makes the Lindemann mechanism work.

The Math

We’ll use the steady-state approximation here. Since \( A^* \) is short-lived and reactive, its concentration stays roughly constant. Rate of formation equals rate of destruction.

Rate of \( A^* \) formation: \( k_f [A]^2 \)

Rate of \( A^* \) destruction: \( k_b [A][A^*] + k_{f_2}[A^*] \)

Setting these equal (steady-state):

$$\frac{d[A^*]}{dt} = k_f [A]^2 – k_b [A][A^*] – k_{f_2}[A^*] = 0 \quad \text{…(1)}$$

Solving for \( [A^*] \):

$$[A^*] = \frac{k_f [A]^2}{k_b [A] + k_{f_2}} \quad \text{…(2)}$$

The reaction rate is:

$$r = -\frac{d[A]}{dt} = k_{f_2}[A^*] \quad \text{…(3)}$$

Substituting equation 2 into equation 3:

$$r = \frac{k_f k_{f_2} [A]^2}{k_b [A] + k_{f_2}} \quad \text{…(4)}$$

This rate law has no definite order. But we can look at two limiting cases.

High Pressure Limit

When \( k_b[A] \gg k_{f_2} \), the \( k_{f_2} \) term in the denominator becomes negligible:

$$r = \frac{k_f k_{f_2}}{k_b}[A] \quad \text{…(5)}$$

First-order kinetics. At high pressures, \( [A] \) is large, so collisions are frequent. The energized molecules get de-energized quickly, and only a small fraction react. The rate-determining step is the unimolecular decomposition of \( A^* \).

Low Pressure Limit

When \( k_{f_2} \gg k_b[A] \), the \( k_b[A] \) term becomes negligible:

$$r = k_f [A]^2 \quad \text{…(6)}$$

Second-order kinetics. At low pressures, collisions are rare. Once \( A^* \) forms, it’s more likely to react than to collide again and lose energy. The rate-determining step is now the bimolecular activation.

The Unimolecular Rate Constant

We define the experimental rate as:

$$r = k_{uni}[A] \quad \text{…(7)}$$

Comparing equations 4 and 7:

$$k_{uni} = \frac{k_f k_{f_2} [A]}{k_b[A] + k_{f_2}}$$

Or equivalently:

$$k_{uni} = \frac{k_f k_{f_2}}{k_b + k_{f_2}/[A]}$$

This shows how \( k_{uni} \) varies with pressure (through \( [A] \)). At high \( [A] \), it approaches a constant. At low \( [A] \), it decreases. This pressure dependence is a key experimental test of the Lindemann mechanism.

Limitations of the Lindemann Theory

The Lindemann mechanism was a breakthrough, but it’s not perfect.

The theory predicts that \( k_{uni} \) should decrease linearly with \( 1/[A] \) at low pressures. Experimentally, the falloff is more gradual. The simple two-step mechanism doesn’t capture all the physics.

Later refinements by Hinshelwood, Rice, Ramsperger, and Kassel (the RRKM theory) accounted for the distribution of energy among vibrational modes. But Lindemann’s core insight, that activation happens through collisions and there’s a time lag before reaction, remains the foundation.

Video Lecture

Got 50 minutes? This lecture walks through the Lindemann mechanism in detail.

Want a PDF version? Download it here.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a unimolecular reaction?

A unimolecular reaction involves a single reactant molecule transforming into products. Examples include isomerization reactions (like cis-trans conversions) and decomposition reactions. The overall stoichiometry is A → P, where one molecule becomes one or more product molecules.

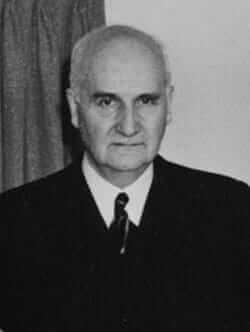

Who was Frederick Lindemann?

Frederick Lindemann (1886-1957) was a German-born British physicist who later became Viscount Cherwell. Beyond his work on reaction kinetics, he served as Winston Churchill’s scientific advisor during World War II. His 1922 mechanism for unimolecular reactions was a foundational contribution to chemical kinetics.

What is an energized molecule (A*)?

An energized molecule (A*) is a reactant molecule that has absorbed enough vibrational energy to potentially react, but hasn’t yet crossed the activation barrier. It’s not an activated complex or transition state. It’s a regular molecule in an excited vibrational state, waiting to either react or lose its excess energy through another collision.

Why does the reaction order change with pressure?

At high pressure, collisions are frequent. Energized molecules quickly lose energy before reacting, so the slow step is the unimolecular decomposition (first-order). At low pressure, collisions are rare. Once a molecule gets energized, it usually reacts before another collision can de-energize it. The slow step becomes the bimolecular activation (second-order).

What is the steady-state approximation?

The steady-state approximation assumes that the concentration of a reactive intermediate stays constant during the reaction. Its rate of formation equals its rate of consumption. This simplification lets us derive rate laws for complex mechanisms without solving difficult differential equations.

What is the Lindemann-Hinshelwood mechanism?

Cyril Hinshelwood extended Lindemann’s work by considering that different collision partners have different efficiencies for energy transfer. The combined theory is called the Lindemann-Hinshelwood mechanism. Hinshelwood shared the 1956 Nobel Prize in Chemistry partly for this work on reaction mechanisms.

What are the limitations of Lindemann theory?

The theory predicts a linear relationship between 1/k and 1/[A] at low pressures, but experiments show a curved falloff. The simple model doesn’t account for how energy distributes among different vibrational modes or how molecular complexity affects reaction rates. RRKM theory addresses these shortcomings.

What is RRKM theory?

RRKM (Rice-Ramsperger-Kassel-Marcus) theory is a more sophisticated treatment of unimolecular reactions. It accounts for how energy distributes among vibrational modes and calculates the probability that enough energy localizes in the reaction coordinate to cause reaction. It’s the modern standard for understanding unimolecular kinetics.

Can inert gases affect unimolecular reaction rates?

Yes. Inert gases can act as collision partners for both activation and de-activation steps. Adding an inert gas increases the total pressure and collision frequency without changing the reactant concentration. This can shift the reaction from the low-pressure regime toward the high-pressure regime, affecting the observed rate constant.

What are real-world examples of unimolecular reactions?

Classic examples include the isomerization of cyclopropane to propene, the decomposition of nitrogen pentoxide (N₂O₅), and the thermal decomposition of azomethane. These reactions follow Lindemann-type kinetics and show the predicted pressure dependence. Many atmospheric and combustion reactions also proceed through unimolecular mechanisms.

its good

Like

Just wanted to tell you there’s a typo in Eq (1) — there should be parentheses around $ k_{-1} \times [A] [A^*] + k_2 \times [A^*]$, so the full expression becomes “$ k_1\times [A]^2 -(k_{-1} \times [A] [A^*] + k_2 \times [A^*])=0$

(Or else the sign in front of $ k_2$ should be negative.)

Just wanted to tell you there’s a typo in Eq (1) — there should be parentheses around $ k_{-1} \times [A] [A^*] + k_2 \times [A^*]$, so the full expression becomes “$ k_1\times [A]^2 -(k_{-1} \times [A] [A^*] + k_2 \times [A^*])=0$

(Or else the sign in front of $ k_2$ should be negative.)

tooo easy i like it

exaplain the limits and drawbacks of lindemann theory

calculated value of collision frequency is many times greater then the actual value of k

explain the flaws of theory and modification.

raely a good explation i also like this explation

i con”t memory that but i did andrestanding very easily

good

Sir, I think the eqⁿ 1 needs to be corrected! It should be

d[A*]/dt = kf [A]² – kb [A*][A] – kf2 [A*] = 0

(Not “+ kf2 [A*]”)

Yes, you are right. I missed the symbol.

Fixed.

Sir, I think the eqⁿ 1 needs to be corrected! It should be

d[A*]/dt = kf [A]² – kb [A*][A] – kf2 [A*] = 0

(Not “+ kf2 [A*]”)

Yes, you are right. I missed the symbol.

Fixed.