Trigonometric Identities

Trigonometric identities are equations involving trig functions that hold true for every valid value of the variable. You’ll use them constantly, whether you’re simplifying expressions, solving equations, or proving other results. They’re the backbone of trigonometry.

Sine, cosine, and tangent are your primary trig functions. Secant, cosecant, and cotangent round out the set. All six build on each other, and the identities below connect them in ways you need to know cold.

What are Trigonometric Identities?

A trigonometric identity is an equation involving trig functions that’s true for all values of the variable where both sides are defined. This isn’t something you verify with one angle and call it done. It has to work everywhere.

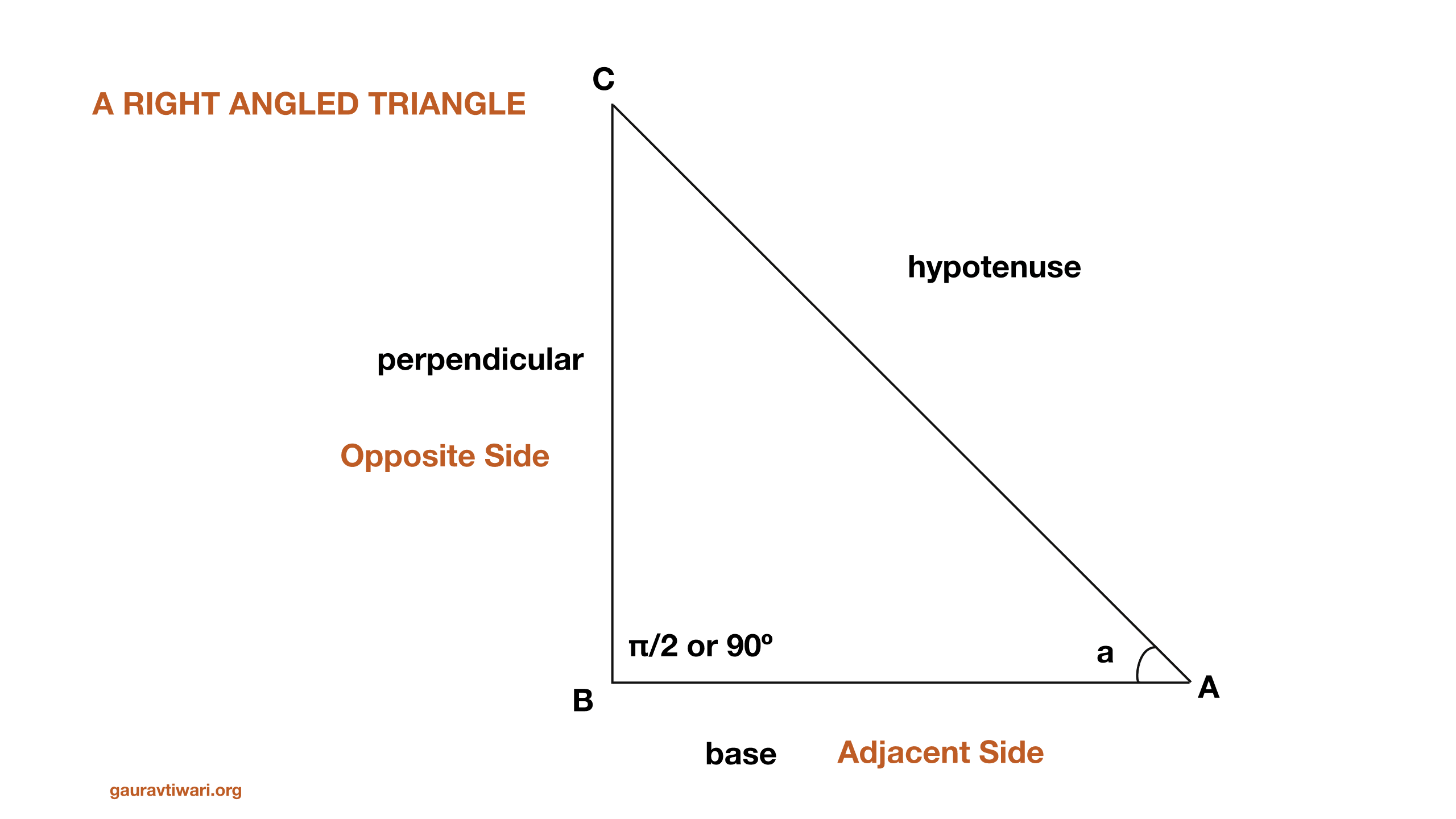

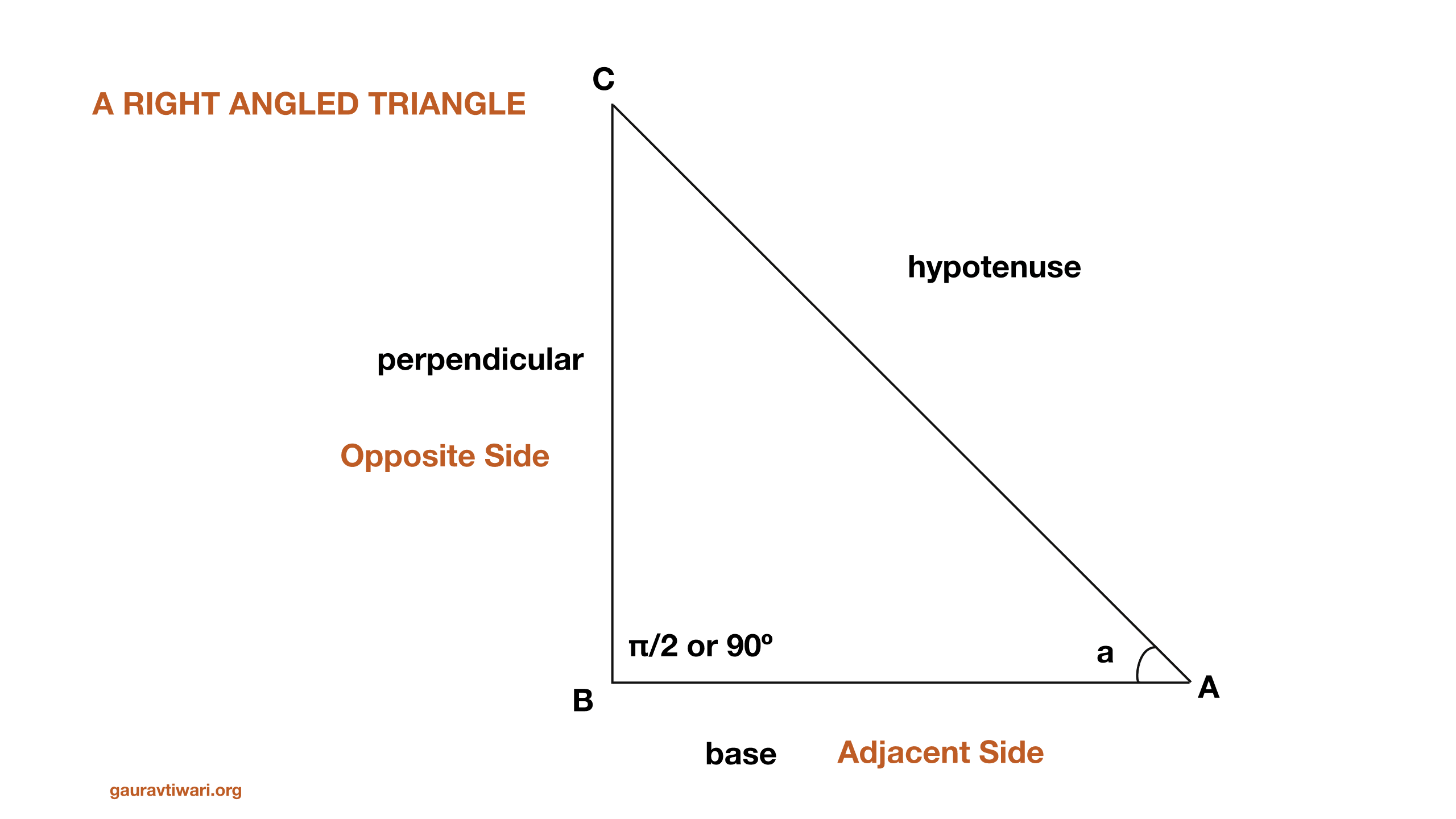

There are many distinct identities, and they involve both the side lengths and angles of a triangle. One thing to keep in mind: most of the basic definitions start with a right-angled triangle.

All trigonometric identities trace back to six ratios: sine, cosine, tangent, cosecant, secant, and cotangent. Each ratio is defined using the sides of a right triangle (adjacent, opposite, and hypotenuse). Once you understand these six, every identity below is just algebra.

Trigonometric Identities

Using a right-angled triangle as your reference, here’s how each trig function is defined.

\(\sin \theta = \frac{\mathbf{Opposite \ side \ (Perpendicular)}}{\mathbf{Hypotenuse}}\)

\(\cos \theta = \frac{\mathbf{Adjacent \ side (Base)}}{\mathbf{Hypotenuse}}\)

\(\tan \theta = \frac{\mathbf{Opposite \ side}}{\mathbf{Adjacent \ side}}\)

\(\sec \theta = \frac{\mathbf{Hypotenuse}}{\mathbf{Adjacent \ side}}\)

\( \mathrm{cosec} \ \theta = \frac{\mathbf{Hypotenuse}}{\mathbf{Opposite \ side}}\)

\(\cot \theta = \frac{\mathbf{Adjacent \ side}}{\mathbf{Opposite \ side}}\)

Ratio Trigonometric Identities

These two identities express tangent and cotangent in terms of sine and cosine. You’ll reach for these constantly when simplifying expressions.

\(\tan \theta = \dfrac{\sin \theta}{\cos \theta}\)

\(\cot \theta = \dfrac{\cos \theta}{\sin \theta}\)

Reciprocal Identities

Each trig function has a reciprocal partner. Memorize these pairs and you’ll move through problems much faster.

\( \mathrm{cosec} \ \theta = \dfrac{1}{\sin \theta}\)

\( \sec \ \theta = \dfrac{1}{\cos \theta}\)

\( \cot \ \theta = \dfrac{1}{\tan \theta}\)

\( \sin \ \theta = \dfrac{1}{\mathrm{cosec} \ \theta}\)

\( \cos \ \theta = \dfrac{1}{\sec \theta}\)

\( \tan \ \theta = \dfrac{1}{\cot \theta}\)

All of these come directly from the right-angled triangle definitions. When you know the height and base of a right triangle, you can find every trig value. The reciprocal identities are just the original ratios flipped.

Periodicity Identities (in Radians)

These are also called co-function identities. They let you shift angles by \(\pi/2\), \(\pi\), \(2\pi\), and so on. You’ll find them especially useful when working with the unit circle.

- \(\sin (\pi/2 – A) = \cos A\) and \(\cos (\pi/2 – A) = \sin A\)

- \(\sin (\pi/2 + A) = \cos A\) and \(\cos (\pi/2 + A) = – \sin A\)

- \(\sin (3\pi/2 – A) = – \cos A\) and \(\cos (3\pi/2 – A) = – \sin A\)

- \(\sin (3\pi/2 + A) = – \cos A\) and \(\cos (3\pi/2 + A) = \sin A\)

- \(\sin (\pi – A) = \sin A\) and \(\cos (\pi – A) = – \cos A\)

- \(\sin (\pi + A) = – \sin A\) and \(\cos (\pi + A) = – \cos A\)

- \(\sin (2\pi – A) = – \sin A\) and \(\cos (2\pi – A) = \cos A\)

- \(\sin (2\pi + A) = \sin A\) and \(\cos (2\pi + A) = \cos A\)

All trig functions are cyclic. They repeat after a fixed period. That period differs by function: sine and cosine repeat every \(2\pi\), while tangent and cotangent repeat every \(\pi\).

Cofunction Identities (in Degrees)

If you prefer working in degrees, here are the same co-function relationships. Each pair swaps when you subtract from 90 degrees.

\(\sin(90°−x) =\cos x\)

\(\cos(90°−x) = \sin x\)

\(\tan(90°−x) = \cot x\)

\(\cot(90°−x) = \tan x\)

\(\sec(90°−x) = \mathrm{cosec} x\)

\(\mathrm{cosec}(90°−x) = \sec x\)

Sum and Difference Identities

These let you break apart the trig function of a sum or difference of two angles. You’ll use them heavily in calculus and in proving other identities.

\(\sin(x+y) = \sin(x)\cos(y)+\cos(x)\sin(y)\)

\(\cos(x+y) = \cos(x)\cos(y)–\sin(x)\sin(y)\)

\(\tan (x+y) = \dfrac{\tan x + \tan y}{1-\tan x \tan y}\)

\(\sin(x–y) = \sin(x)\cos(y)–\cos(x)\sin(y)\)

\(\cos(x–y) = \cos(x)\cos(y) + \sin(x)\sin(y)\)

\(\tan (x-y) = \dfrac{\tan x – \tan y}{1+\tan x \tan y}\)

Double Angle Identities

Double angle formulas give you the trig values of \(2x\) in terms of \(x\). These show up everywhere, from integration to signal processing.

\(\sin 2x = 2 \sin x \cos x = \dfrac{2 \tan x}{1+\tan^2 x}\)

\(\cos 2x = \cos^2 x – \sin^2 x = \dfrac{1-\tan^2 x}{1 + \tan^2 x}\)

\(\cos(2x) = 2\cos^2(x)−1 = 1–2\sin^2(x)\)

\(\tan 2x = \dfrac{2 \tan x}{1-\tan^2 x}\)

\(\sec 2x = \dfrac{\sec^2x}{2-\sec^2 x}\)

\(\mathrm{cosec} 2x = \frac{1}{2} \sec x \ \mathrm{cosec} x\)

Triple Angle Identities

These express trig functions of \(3x\) in terms of \(x\). They’re less common than double angle formulas but still worth knowing for competitive exams and advanced problem solving.

\(\sin 3x = 3\sin x – 4\sin^3x\)

\(\cos 3x = 4\cos^3x-3\cos x\)

\(\tan 3x = \dfrac{3 \tan x – \tan^3 x}{1-3 \tan^2 x}\)

Half Angle Identities

Half angle identities let you find trig values of \(x/2\) when you know the value at \(x\). The plus-or-minus sign depends on the quadrant where \(x/2\) falls.

\(\sin \dfrac{x}{2} = \pm \sqrt{\dfrac{1-\cos x}{2}}\)

\(\cos \dfrac{x}{2} = \pm \sqrt{\dfrac{1+\cos x}{2}}\)

\(\tan \dfrac{x}{2} = \sqrt{\dfrac{1-\cos x}{1+\cos x}} = \dfrac{1-\cos x}{\sin x}\)

Product Identities

Product-to-sum identities convert a product of two trig functions into a sum. These are particularly handy when you’re integrating products of sines and cosines.

\(\sin x \cos y = \dfrac{\sin (x+y)+ \sin (x-y)}{2}\)

\(\cos x \cos y = \dfrac{\cos (x+y)+ \cos (x-y)}{2}\)

\(\sin x \sin y = \dfrac{\cos (x-y)- \cos (x+y)}{2}\)

Sum to Product Identities

These work the other way: they convert a sum or difference of trig functions into a product. You’ll find them useful for solving equations where you need to factor expressions.

\(\sin x + \sin y = 2 \sin \frac{(x+y)}{2} \cos \frac{(x-y)}{2}\)

\(\sin x – \sin y = 2 \cos \frac{(x+y)}{2} \sin \frac{(x-y)}{2}\)

\(\cos x + \cos y = 2 \cos \frac{(x+y)}{2} \cos \frac{(x-y)}{2}\)

\(\cos x – \cos y = -2 \sin \frac{(x+y)}{2} \sin \frac{(x-y)}{2}\)

Pythagorean Trigonometric Identities

These three identities come directly from the Pythagorean theorem. They’re probably the most used identities in all of trigonometry, so make sure you know them by heart.

\(\sin^2 a + \cos^2 a = 1\)

\(1+\tan^2 a = \sec^2 a\)

\(\mathrm{cosec}^2 a = 1 + \cot^2 a\)

Trigonometric Identities of Opposite Angles

When you negate an angle, some trig functions flip sign and others don’t. Cosine and secant are even functions (they stay the same), while sine, tangent, cotangent, and cosecant are odd functions (they flip sign).

\(\sin (-\theta) = – \sin \theta\)

\(\cos (-\theta) = \cos \theta\)

\(\tan (-\theta) = – \tan \theta\)

\(\cot (-\theta) = – \cot \theta\)

\(\sec (-\theta) = \sec \theta\)

\(\mathrm{cosec} \ (-\theta) = – \mathrm{cosec} \ \theta\)

Trigonometric Identities of Complementary Angles

Two angles are complementary when they add up to 90 degrees. The trig function of one equals the co-function of the other. This is actually where the “co” in cosine, cotangent, and cosecant comes from.

\(\sin (90° – \theta) = \cos \theta\)

\(\cos (90 ° – \theta) = \sin \theta\)

\(\tan (90 ° – \theta) = \cot \theta\)

\(\cot (90 °– \theta) = \tan \theta\)

\(\sec (90 °– \theta) = \mathrm{cosec} \ \theta\)

\(\mathrm{cosec} \ (90 ° – \theta) = \sec \theta\)

Trigonometric Identities of Supplementary Angles

Two angles are supplementary when they add up to 180 degrees. Here’s how each trig function behaves when you subtract your angle from 180 degrees.

\(\sin (180°- \theta) = \sin\theta\)

\(\cos (180°- \theta) = -\cos \theta\)

\(\mathrm{cosec} \ (180°- \theta) = \mathrm{cosec} \ \theta\)

\(\sec (180°- \theta)= -\sec \theta\)

\(\tan (180°- \theta) = -\tan \theta\)

\(\cot (180°- \theta) = -\cot \theta\)

Proofs of Trigonometric Identities

Now let’s prove the three Pythagorean identities. These aren’t arbitrary formulas. They follow directly from the Pythagorean theorem applied to a right-angled triangle. Consider a right-angled \(\triangle ABC\), which is right-angled at B.

Applying the Pythagorean theorem to this triangle, you get:

(hypotenuse)2 = (base)2 + (perpendicular)2

\(AC^2 = AB^2+BC^2 \ldots (1)\)

Trigonometric Identity 1

Divide each term of equation (1) by \(AC^2\):

\(\dfrac{AC^2}{AC^2} = \dfrac{AB^2}{AC^2} + \dfrac{BC^2}{AC^2}\)

\(\implies \dfrac{AB^2}{AC^2} + \dfrac{BC^2}{AC^2} =1\)

\(\implies (\dfrac{AB}{AC})^2 + (\dfrac{BC}{AC})^2 = 1 \ldots (2)\)

You know that \( \dfrac{AB}{AC}\) is \(\cos a\) and \(\dfrac{BC}{AC}\) is \(\sin a\).

Substituting into equation \((2)\):

\(\sin^2a + \cos^2a = 1\)

This identity is valid for angles \(0\leq a \leq 90 °\).

Trigonometric Identity 2

Now divide equation \((1)\) by \(AB^2\):

\(\dfrac{AC^2}{AB^2} = \dfrac{AB^2}{AB^2} + \dfrac{BC^2}{AB^2}\)

\(\implies \dfrac{AC^2}{AB^2} =1 + \dfrac{BC^2}{AB^2}\)

\(\implies (\dfrac{AC}{AB})^2 = 1+ (\dfrac{BC}{AB})^2 \ldots (3)\)

Here, \( \dfrac{AC}{AB}\) is the inverse of \(\cos a\), which is \(\sec a\), and \(\dfrac{BC}{AB}\) is \(\tan a\).

Replacing the values in equation \((3)\):

\(1+\tan^2a = \sec^2a \ldots (4)\)

Since \(\tan a\) is not defined for \(a = 90°\), this identity holds true for \(0 \leq a \lt 90°\).

Trigonometric Identity 3

Similarly, dividing equation \((1)\) by \(BC^2\) gives you:

\(\mathrm{cosec}^2 \ a = 1 + \cot^2 a \ldots (5)\)

Since \(\mathrm{cosec} \ a\) and \(\cot a\) are not defined for \(a = 0°\), this identity holds for all values where \(0°\lt a \leq 90°\).

Triangle Identities (Sine, Cosine, and Tangent Rules)

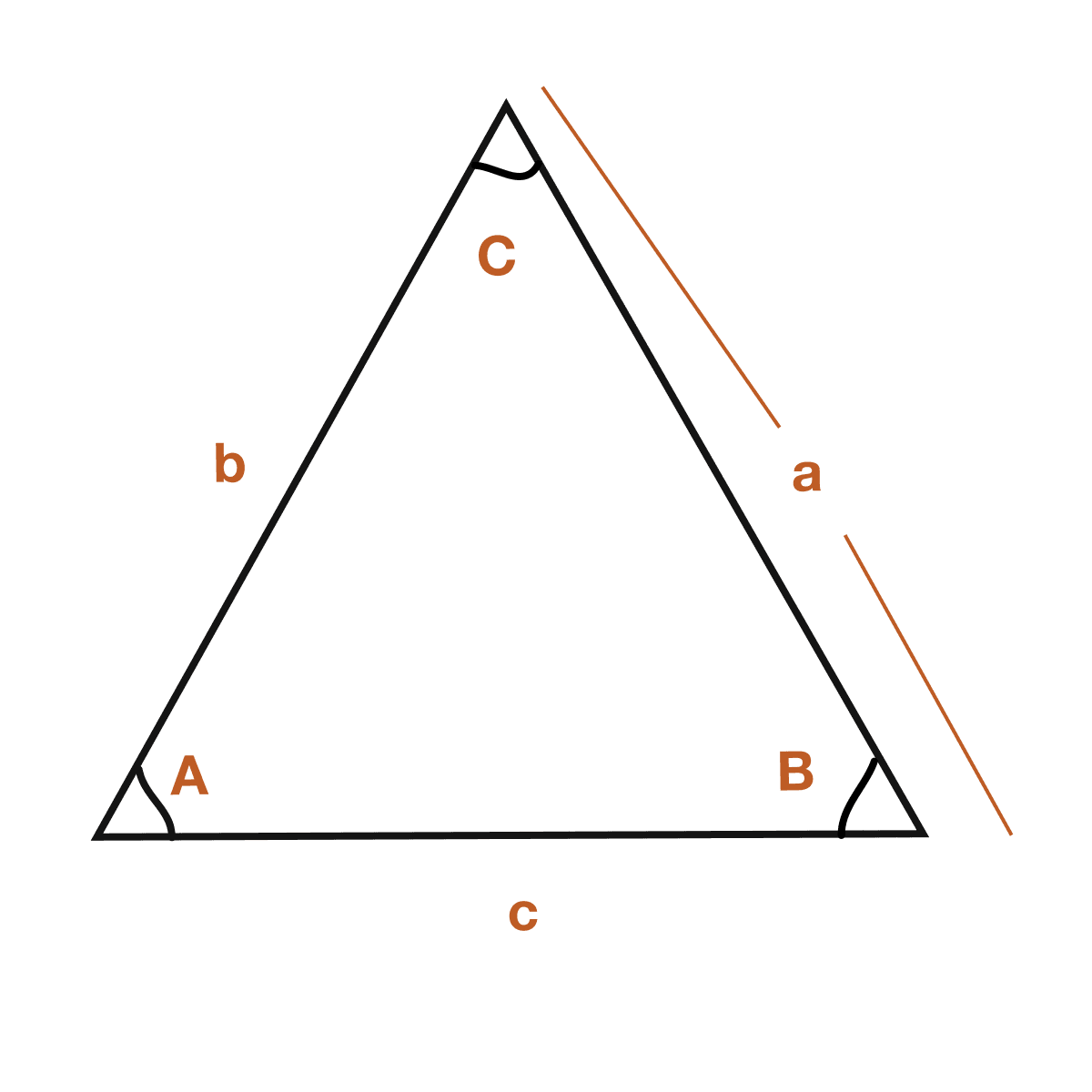

The identities above apply specifically to right-angled triangles. But there are three rules that work for any triangle at all. These are the sine rule, cosine rule, and tangent rule.

- Sine law

- Cosine law

- Tangent law

Also see: Triangle Inequality

Sine Law

If \(A\), \(B\) and \(C\) are the vertices of a triangle, and \(a\), \(b\) and \(c\) are the opposite sides respectively, the sine rule states:

\(\dfrac{a}{\sin A} = \dfrac{b}{\sin B} = \dfrac{c}{\sin C} \)

or equivalently, \(\dfrac{\sin A}{a} = \dfrac{\sin B}{b} = \dfrac{\sin C}{c} \)

Cosine Law

The cosine rule generalizes the Pythagorean theorem to any triangle. When angle \(C\) is 90 degrees, the \(\cos C\) term drops to zero and you get the standard Pythagorean theorem back.

\(c^2 = a^2 + b^2 – 2ab \cos C\)

or, \(\cos C = \dfrac{a^2 + b^2 – c^2}{2ab}\)

Tangent Law

The tangent rule (also called the law of tangents) relates the sides and angles of any triangle:

\(\dfrac{a-b}{a+b} = \dfrac{\tan \frac{A-B}{2}}{\tan \frac{A+B}{2}}\)

What are the three basic Pythagorean trigonometric identities?

The three Pythagorean identities are: (1) sin²a + cos²a = 1, (2) 1 + tan²a = sec²a, and (3) cosec²a = 1 + cot²a. All three are derived directly from the Pythagorean theorem applied to a right-angled triangle. The first identity is the most fundamental, and the other two are obtained by dividing through by cos²a and sin²a respectively.

How do you use the double angle identities?

Double angle identities express trig functions of 2x in terms of x. For example, sin 2x = 2 sin x cos x, and cos 2x = cos²x – sin²x. You use them to simplify expressions, solve equations, and evaluate integrals. They also have alternate forms: cos 2x = 2cos²x – 1 = 1 – 2sin²x, which are useful when you want to eliminate either sine or cosine from an expression.

What is the difference between complementary and supplementary angle identities?

Complementary angles add up to 90 degrees, while supplementary angles add up to 180 degrees. For complementary angles, each trig function equals the co-function of its complement (e.g., sin(90° – x) = cos x). For supplementary angles, sine and cosecant keep their sign (e.g., sin(180° – x) = sin x), while cosine, secant, tangent, and cotangent change sign (e.g., cos(180° – x) = -cos x).

Why do some trig functions change sign with negative angles and others don’t?

This comes down to whether the function is even or odd. Cosine and secant are even functions, meaning cos(-x) = cos x and sec(-x) = sec x. Sine, tangent, cotangent, and cosecant are odd functions, so they flip sign: sin(-x) = -sin x, tan(-x) = -tan x, and so on. Geometrically, reflecting an angle across the x-axis doesn’t change the horizontal coordinate (cosine), but it negates the vertical coordinate (sine).

When should you use sum-to-product vs product-to-sum identities?

Use product-to-sum identities when you have a product of two trig functions and need to convert it into a sum, which is common in integration problems. Use sum-to-product identities when you have a sum or difference of trig functions and need to factor it into a product, which helps when solving trig equations. The choice depends on which form makes your specific problem easier to work with.

How are the sine, cosine, and tangent rules different from standard trig identities?

Standard trig identities (like the Pythagorean identities and reciprocal identities) apply to angles and are based on right-angled triangles. The sine, cosine, and tangent rules are different because they apply to any triangle, not just right-angled ones. They relate the sides of a triangle to its angles. The cosine rule, for instance, is a generalization of the Pythagorean theorem that accounts for non-right angles.

This is better than most paid courses I’ve taken on trigonometric identities. Clear, concise, and well-organized.

The FAQs at the bottom cleared up some misconceptions I had about trigonometric identities. Really thoughtful addition.

This explanation of trigonometric identities is exactly what I needed for my semester exams. The step-by-step approach makes it so much easier to follow than my textbook.

Finally a resource that explains trigonometric identities without assuming you already know everything. Perfect for self-study.

This explanation of trigonometric identities is exactly what I needed for my semester exams. The step-by-step approach makes it so much easier to follow than my textbook.

Bookmarked this page. Your way of explaining trigonometric identities is clear and straightforward. Would love to see more examples with solutions.

I’ve been struggling with trigonometric identities for weeks and this finally made it click. The worked examples are particularly helpful.

I’ve been struggling with trigonometric identities for weeks and this finally made it click. The worked examples are particularly helpful.

Could you add more practice problems at the end? The content is excellent, I just want more to work through.

I come back to this page every time I need to revise trigonometric identities. It is one of the most reliable resources I have found online.

I come back to this page every time I need to revise trigonometric identities. It is one of the most reliable resources I have found online.

The section on sum and product formulas was eye-opening. I never thought about it from that angle before. Thank you for this resource.

The examples here really bridge the gap between theory and problem-solving. Helped me a lot with my homework.

Shared this with my study group. We all found the sum and product formulas section very helpful for our assignments.

Your explanations remind me of my favorite professor. Detailed yet easy to understand. Keep up the great work.