Radius of Convergence and Interval of Convergence Calculator

Here’s the thing about power series: knowing where they converge is half the battle. The Radius of Convergence Calculator below does the heavy lifting—enter your series, and it spits out both the radius and interval of convergence in seconds.

I built this tool because calculating convergence by hand is tedious and error-prone. Let me show you how to use it, then we’ll dig into the theory.

Radius of Convergence Calculator

How to Use This Calculator

This calculator uses the Ratio Test to find your radius of convergence, then tests the endpoints to determine the exact interval. Here’s how to get accurate results:

Step-by-Step Instructions

- Enter the nth coefficient \( a_n \) — This is the coefficient formula WITHOUT the \( (x-a)^n \) part. Use

nas your index variable. - Set the center \( a \) — This is the point around which your power series is centered. Default is 0.

- Click “Calculate Convergence” — The calculator displays the radius, tests both endpoints, and gives you the complete interval.

Input Syntax Guide

| What You Want | How to Type It | Example Series |

|---|---|---|

| Fractions | 1/n or n/(n+1) | \( \sum \frac{1}{n} x^n \) |

| Exponents | n^2 or 2^n | \( \sum n^2 x^n \) |

| Alternating signs | (-1)^n | \( \sum (-1)^n x^n \) |

| Factorials | factorial(n) | \( \sum \frac{x^n}{n!} \) |

| Combined | (-1)^n / factorial(n) | \( \sum \frac{(-1)^n x^n}{n!} \) |

| With constants | n / 2^n | \( \sum \frac{n x^n}{2^n} \) |

Worked Example

Let’s find the convergence of \( \displaystyle\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{n(x-3)^n}{2^n} \)

Input:

- \( a_n \):

n / 2^n - Center:

3

Output:

The series \( \displaystyle\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{n(x-3)^n}{2^n} \) converges when \( |x – 3| < 2 \). Radius of convergence: \( R = 2 \). Interval of convergence: \( (1, 5) \).

The calculator found that \( R = 2 \), so the interval spans from \( 3 – 2 = 1 \) to \( 3 + 2 = 5 \). After testing the endpoints, neither converged, giving us the open interval \( (1, 5) \).

What is the Radius of Convergence?

The radius of convergence is a number \( R \) that tells you exactly where a power series behaves. For the series:

$$\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} c_n (x – a)^n$$

The series will:

- Converge when \( |x – a| < R \)

- Diverge when \( |x – a| > R \)

- Maybe converge, maybe diverge when \( |x – a| = R \) (requires separate endpoint testing)

Think of \( R \) as the “safe zone” radius around the center \( a \). Inside that zone, your series converges. Outside, it diverges. On the boundary? You have to check each endpoint individually.

Want to understand the theory behind this? See my article on D’Alembert’s Ratio Test for the mathematical foundation.

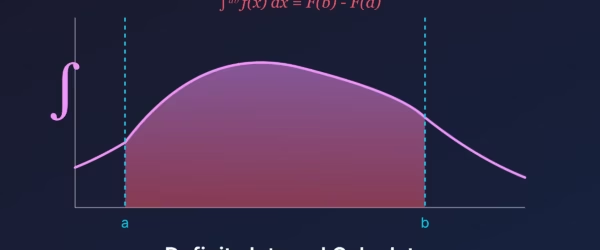

Interval of Convergence

The interval of convergence is the complete set of \( x \)-values where your series converges. It’s related to the radius, but not identical.

If your radius is \( R \) and center is \( a \), then your interval is somewhere in the range \( (a – R, a + R) \). The exact interval depends on what happens at the endpoints:

- Open interval \( (a-R, a+R) \) — neither endpoint converges

- Closed interval \( [a-R, a+R] \) — both endpoints converge

- Half-open \( [a-R, a+R) \) or \( (a-R, a+R] \) — one endpoint converges

Radius of Convergence in Real Analysis

Let me give you the formal definition. For real-valued power series:

Let \( \psi \in \mathbb{R} \) be a real number. Consider the power series about \( \psi \):

$$S(x) = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} a_n (x – \psi)^n$$

Let \( I \) be the interval of convergence of \( S(x) \), with endpoints \( \psi – R \) and \( \psi + R \).

Since \( \psi \) is the midpoint of \( I \), the value \( R \) is called the radius of convergence of \( S(x) \).

Radius of Convergence in Complex Analysis

In the complex plane, the concept extends naturally. For \( \psi \in \mathbb{C} \) and \( z \in \mathbb{C} \), consider:

$$f(z) = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} a_n (z – \psi)^n$$

The radius of convergence is the extended real number \( R \in \overline{\mathbb{R}} \) defined by:

$$R = \inf \left\{ |z – \psi| : z \in \mathbb{C}, \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} a_n (z – \psi)^n \text{ diverges} \right\}$$

In other words, \( R \) is the distance from the center to the nearest point where the series diverges. Geometrically, this creates a disk of convergence in the complex plane.

Common Power Series Reference Table

Here are the power series you’ll encounter most often, along with their intervals of convergence. Bookmark this—you’ll use it constantly.

| Function | Power Series | Interval |

|---|---|---|

| \( e^x \) | \( \displaystyle\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{x^n}{n!} \) | \( \mathbb{R} \) (all real numbers) |

| \( \sin(x) \) | \( \displaystyle\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^n x^{2n+1}}{(2n+1)!} \) | \( \mathbb{R} \) |

| \( \cos(x) \) | \( \displaystyle\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^n x^{2n}}{(2n)!} \) | \( \mathbb{R} \) |

| \( \sinh(x) \) | \( \displaystyle\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{x^{2n+1}}{(2n+1)!} \) | \( \mathbb{R} \) |

| \( \cosh(x) \) | \( \displaystyle\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{x^{2n}}{(2n)!} \) | \( \mathbb{R} \) |

| \( \frac{1}{1-x} \) | \( \displaystyle\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} x^n \) | \( |x| < 1 \) |

| \( \frac{1}{1+x} \) | \( \displaystyle\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} (-1)^n x^n \) | \( |x| < 1 \) |

| \( \ln(1+x) \) | \( \displaystyle\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^{n+1} x^n}{n} \) | \( |x| < 1 \) |

| \( \ln(1-x) \) | \( \displaystyle -\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{x^n}{n} \) | \( |x| < 1 \) |

| \( \tan^{-1}(x) \) | \( \displaystyle\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^n x^{2n+1}}{2n+1} \) | \( |x| < 1 \) |

| \( \ln(x) \) | \( \displaystyle\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^n (x-1)^n}{n} \) | \( |x – 1| < 1 \) |

| \( \ln\left(\frac{1+x}{1-x}\right) \) | \( \displaystyle 2\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{x^{2n+1}}{2n+1} \) | \( |x| < 1 \) |

Key Points to Remember

- Radius is always non-negative. You’ll get \( R \geq 0 \), with \( R = 0 \) meaning convergence only at the center, and \( R = \infty \) meaning convergence everywhere.

- Interval ≠ Radius. The radius tells you the distance from center; the interval tells you the actual set of converging \( x \)-values including endpoint behavior.

- Always test endpoints separately. The Ratio Test is inconclusive at \( |x – a| = R \). Use other tests (comparison, alternating series, etc.) at the boundaries.

- Complex analysis gives disks, not intervals. In \( \mathbb{C} \), the radius defines a disk of convergence centered at \( \psi \).

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the radius of convergence of a power series?

The radius of convergence R is the distance from the center of a power series to the boundary where convergence ends. For a series centered at a, it converges when |x – a| R. At |x – a| = R, convergence must be tested separately at each endpoint.

How do you find the radius of convergence?

The most common method is the Ratio Test: R = lim(n→∞) |aₙ/aₙ₊₁|. You can also use the Root Test: R = 1/lim(n→∞) |aₙ|^(1/n). Both methods give the same radius. This calculator uses the Ratio Test automatically.

What is the difference between radius and interval of convergence?

The radius R is a single number representing distance from center. The interval of convergence is the actual set of x-values where the series converges, written in interval notation like (a-R, a+R), [a-R, a+R], etc. The interval accounts for endpoint behavior; the radius does not.

Can the radius of convergence be zero or infinity?

Yes to both. R = 0 means the series only converges at the center point (like Σn!xⁿ). R = ∞ means the series converges for all real numbers (like the exponential series Σxⁿ/n!). These are edge cases but occur with common functions.

Why do I need to test endpoints separately?

The Ratio Test is inconclusive when the limit equals 1, which happens exactly at the endpoints where |x – a| = R. At these points, the series might converge or diverge depending on the specific coefficients. You need other tests like the Alternating Series Test or Comparison Test to determine endpoint behavior.

How do I enter factorials in the calculator?

Use factorial(n) for n!. For example, to enter the series Σxⁿ/n!, type 1/factorial(n) as the coefficient. For (2n)!, use factorial(2*n). The calculator understands standard mathematical notation.

What does the center of a power series mean?

The center (often called a or ψ) is the point around which the series is expanded. For Σcₙ(x-a)ⁿ, the center is a. A series centered at 0 is called a Maclaurin series. The center is always the midpoint of the interval of convergence.

Why does the exponential series converge everywhere?

For eˣ = Σxⁿ/n!, applying the Ratio Test gives R = lim(n→∞) |n!/(n+1)!| = lim(n→∞) 1/(n+1) = 0… wait, that’s the reciprocal. Actually, R = lim(n→∞) |(n+1)!/n!| · |1/1| = lim(n→∞) (n+1) = ∞. The factorial in the denominator grows faster than any power of x, so the series converges everywhere.

What if my series starts at n=1 instead of n=0?

The starting index doesn’t affect the radius of convergence. Whether your series starts at n=0, n=1, or any other integer, the radius depends only on the behavior of coefficients as n approaches infinity. The calculator handles any starting index correctly.

How is radius of convergence used in complex analysis?

In complex analysis, the radius defines a disk of convergence in the complex plane, not just an interval on the real line. The series converges for all complex z satisfying |z – ψ| < R. The radius equals the distance from the center to the nearest singularity of the function being represented.